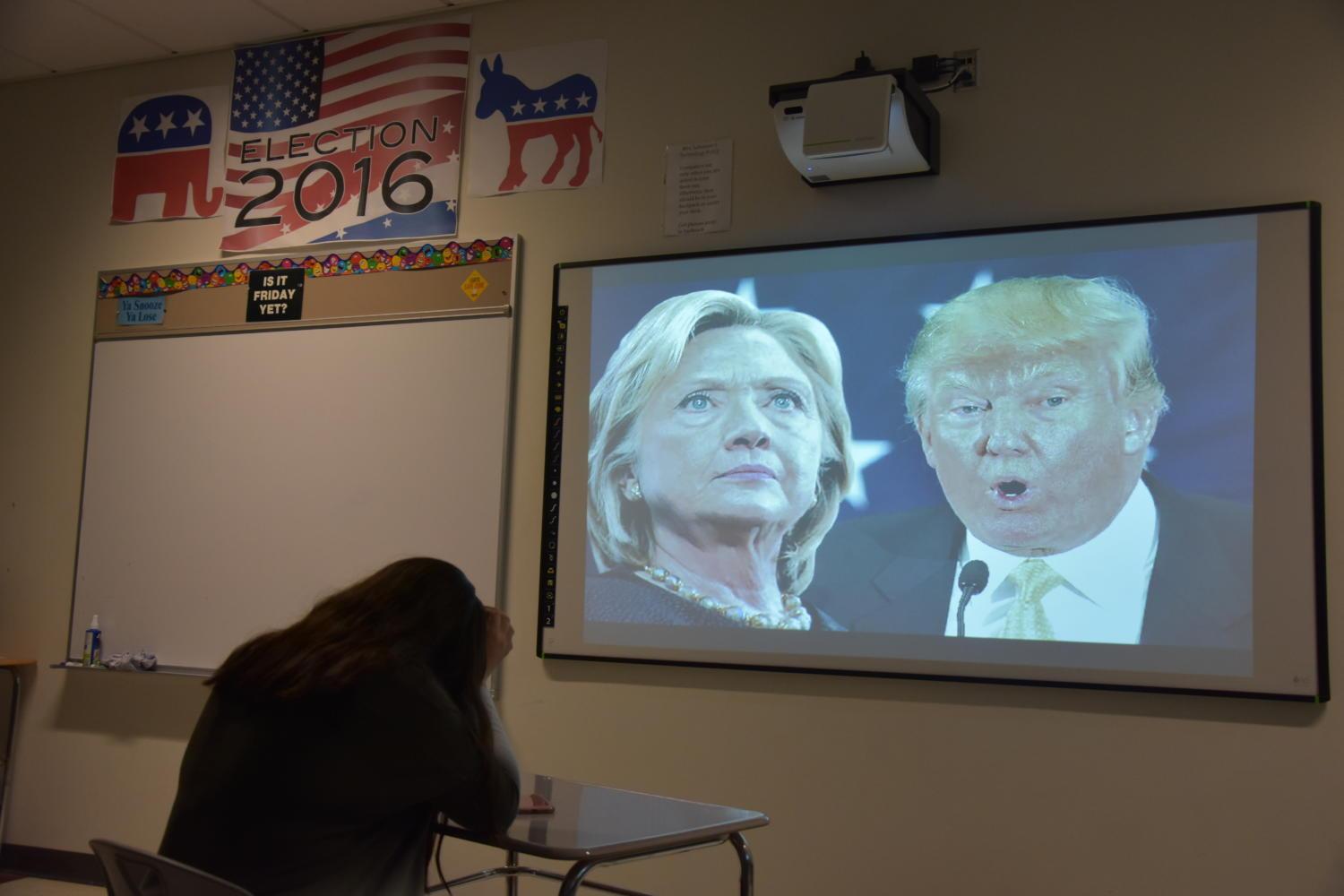

Credit: Andrew D’Amico

Photo Illustration: A student expresses their feelings toward the 2016 election. A similar sentiment is evident in students who identify themselves as having minority political views. “The majority political standpoint in the high school is liberal-sided,” senior Tyler Johnsen said. “I would definitely say conservatives are very much in the minority and get singled out quite frequently.”

Teachers’ views on WHS’ political acceptance differ from students’

Think back to the 2016 election season at WHS. Teachers were excitedly preparing their class’ curricular coverage of the election, outlining lesson plans and scanning through articles to supplement their teachings. Most students were just as eager to learn, preparing notes and thinking about possible essay topics and arguments. However, some students dreaded going to classes with election coverage, scared that expressing their political views would decrease their grades or cause them to be disliked by their teacher and fellow students alike.

Although they seem to be on the same page at WHS, students and teachers have largely different ideas on the political climate of the school.

A survey conducted by WSPN in the spring of 2016 found that 61.2% of students surveyed felt that minority political views are suppressed at the school, while merely 25.0% of teachers felt the same way.

“I would say that [student minority political views] are absolutely marginalized at WHS,” said an anonymous member of WHS’ Class of 2017. “Teachers, especially those in the history and English departments, typically push endless left-wing political opinions and readings on students.”

Some students felt differently.

“I think there are definitely some views that just shouldn’t be welcome in our community,” senior Yaniv Goren said. “And I think largely the views that are suppressed at Wayland are [these] views.”

As for teachers, there was a wide variety of beliefs. Some agreed with the majority of the student body.

“There are some students that do feel shut out of conversations or shut down, and that’s concerning to me,” Principal Allyson Mizoguchi said.

Wellness teacher Rachel Hanks and Mizoguchi shared similar views.

“It probably doesn’t feel all that safe to say what you think right now,” Hanks said. “Is it oppression? Yes, they probably learned it that way. But I’m hoping that teaching people how to listen – teachers too – will help us find common ground.”

Others opposed it, arguing that the school was open to all ideas as a whole.

“I think overall, we are more than willing as a staff to listen to what supporters had to say as long as it didn’t go against the basic values and ideals that we hold as a school and as a community,” history teacher David Schmirer said.

“I think [WHS] is very accepting,” English teacher Sara Snow said. “I think people are very kind and attune to suffering, justice and other good things.”

Regarding the issue of whether students would receive a lower grade for writing a minority view essay, the majority of teachers and students held radically opposing views.

“[I would] absolutely receive [a lower grade]. I’m actually [writing a paper against my views right now],” sophomore Myle Larsen said. Larsen identifies as a conservative. “I would say that there’s probably no way to get rid of political bias, but they should grade it heavily on what the person is actually saying rather than whether they agree with what the person is saying.”

“[A student’s views] would not affect my [grading],” Schmirer said. “I live in a world of facts. In the history department, we use facts to back up our opinion. You got the facts in your paper to back it up, then you’re going to do well on whatever that paper is. I’m going to assume that most of my colleagues do the same.”

Mizoguchi noted that some students may feel uncomfortable presenting their political views in class due to possible teacher and student suppression.

“We have a responsibility as educators and as a school community to be able to hear all voices and to welcome them,” Mizoguchi said. “The problem is, some of the issues that are currently being discussed, such as immigration and civil rights, are really important issues that bring a lot of emotion from people, so sometimes it’s hard to have those discussions.”

She also emphasized that the faculty was working hard to solve the problem of students being shut down.

“As a staff, we have talked about the difficulty and the challenges when we are trying to navigate through controversial issues,” Mizoguchi said. “During heightened political times like now, [we ask ourselves,] ‘how do we make sure everybody’s voice can be heard and is respected?’”