Your donation will support the student journalists of Wayland High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, cover our annual website hosting costs and sponsor admission and traveling costs for the annual JEA journalism convention.

A conversation with Kevin Delaney on his Memorial Day Keynote Address

June 17, 2021

Wayland High School history teacher and department head Kevin Delaney delivered his Memorial Day Key Note Address Monday, May 31, 2021, at the Lakeview Cemetery in Wayland. Below, Delaney details the long and thoughtful process of researching, writing and delivering the address.

How did you come up with the idea to follow these two boys through their lives? What inspired you?

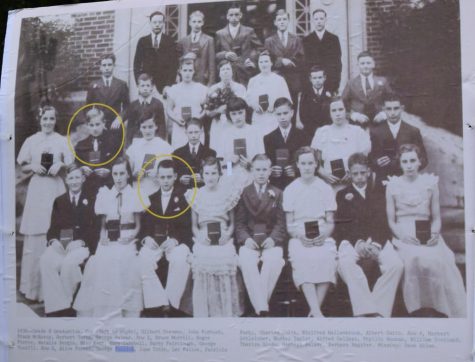

I have done a lot of projects over the years with students dealing with local or regional history themes and done a couple of World War Two projects, and so I knew just from prior student inquiry that, I think about eight or ten or eleven, Wayland World War Two guys never made it home, and we were doing a project–it must have been attic archeology or something about two years ago–we were looking at the Cochituate School. There was this great collection of Cochituate School photographs in a book that folks who were graduates of the Cochituate School had put together in the 1970s as part of the town’s bicentennial, so this was 1976. Flipping through it, I recognized that there were a couple of boys who were featured in that eight grade photograph who were on the “killed in action” list, and then I was curious what happened to all the other boys.

[The other boys] all survived, but about two thirds or three quarters of the boys in that shot ended up in the war. No surprises, right? They’re about 14, and the war for us began in about 1941. I was just imagining the difference between what those boys and girls in that shot were thinking and what was happening in the world in that same moment. Then of course what we knew happened more broadly in the subsequent years. It was a little poignant for me to look at these kids and know they were going to be snuffed out by the fascists in the mid 1940s, so I wanted to try and retrieve their stories the best we could, and we were able to do some of that.

How did you go about conducting research for the address? Was it difficult to find information about their lives?

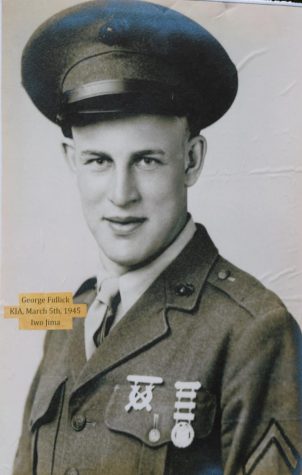

You just have to know what lens to look through. It’s actually pretty straightforward. I was lucky, in a way, because in 2003 I had interviewed one of the two guys’ little sister Jenny Pinkle–she died a couple years ago, four years ago I think–and as part of a project, [which was] about twenty years ago now, somebody told me, “Oh did you know that George Fullick’s little sister is alive?“ and I’m like, “no!” Her name is Jenny Pinkle now, her married name, so I called her up and she was like “yeah, come on over, I’d love to talk to you,” and she’d brought out a box of things she had saved from her brothers’ years when he was only 21 or 22. And she remembered so much about him and vividly. It was almost like her big brother had only been gone six months rather than 60 years.

She kept all of his letters, and she told me this story about going to the club the night before he was shipped out, and how Tommy Dorsey had called him out, and he said such a sweet thing about his sister. When there was this really famous musician, Tommy Dorsey kind of called out, “Hey, I like your girlfriend!” and George was like “I haven’t found one like my sister yet!” So it was just really touching. So, I had done an interview. Without that interview from almost twenty years ago, the story would have been so much more shallow, tut between ancestry dot com and lots of other resources you can get online, whether they are newspapers or other archives, there’s just lots of bits and pieces you can put together. It becomes sort of like this treasure hunt, and it becomes sort of like this picture of a puzzle. You know how you do an actual puzzle and slowly but surely the picture’s forming? That’s kind of like doing history, except most of the puzzle pieces remain missing. And you get a general idea of what the picture was, but you always have that amazingly frustrating experience when you get down to the last few pieces and the box is empty. In history, its kind of like half the puzzle pieces are missing.

This is kind of a pointed question, but in your address and what we’ve been talking about here speaks to the importance of including human elements to history. Could you talk a little more about why it’s important to include that in a historical perspective?

I think you’re right. I think the more intimate we can make our understanding of the people who walked around here in the past, the better our understanding is. It’s too easy in history classes just to look at the raw numbers: oh yeah, the civil war, 600,000 people, or here’s what life was like in the factories, or whatever, and you can kind of intellectualize and you can understand that it’s real but until you get to an actual person’s story and you get to see a picture of his mom or her mom hugging as a baby and it just makes you understand in a much more deep way that this was someone everyone around them loved, just like your parents love you. They had someone just like that loving them, and the feeling was reciprocated. They had all these joys and adventures, all the same things we do, but of course I sometimes wonder what happened to all those things? Do they just dissipate like mist? All those emotions and memories. They do, I guess. But once you get to know someone personally like that, like listening to his sister talk about her big brother. I have a big brother–I have five brothers and sisters–and I adored my brother. Still do. We’re best friends. And it just brings it home in a different way. It would be like if my big brother Pete just went off and never came home. It just adds a level of empathy to our understanding that’s hard to reproduce. This is a way of engendering that. We become more sympathetic to people in the past and maybe more understanding of our contemporaries.

During your speech it really struck me that war and the military used to be really a universal experience for an entire generation. Now we’re so far away from it; the way we talk about war and the military is so different.

Yeah, I agree. Although, your grandchildren will be talking about the COVID era and what was that like. In fifty seventy years from now, we’ll look back and there were almost 600,000 Americans who died, and what was that like? And someone will tap into interviewing you and finding out first hand what you lost. Maybe not much, but maybe a ton. Maybe a grandparent. Certainly what you take for granted was fundamentally disrupted. This is pretty epic times, but we’re all living through all these things that are happening all the time, and we’re just kind of traveling through time on remote control, and the further you get from it, the more reflective you are of it.

And then when the next generation comes, they’re like, you lived through 9/11? What was that like? Or, you guys lived through the COVID-19 era. What was that like? And we’ll be telling stories about it and people will be like “oh my god, I can’t believe you lived through that,” and you’ll be like “yeah, it was bad, but it was also just life.” It’s just what happens. There will be something that’s terrible or challenging that the next generation will deal with in the same way.

What were you hoping listeners would take away from your speech?

I think I wanted them to understand what I already described. That these were two young men who lived and loved and were lost. What I really struggled with with that speech was that it was supposed to be a sort of eulogy, and I didn’t want it to become too politicized. But Memorial Day is kind of a political event. It’s a different sort of political event and it’s not one that should be abused. We attribute a lot to the men and women who didn’t make it home in terms of our democracy and what we often take for granted. One of the things I was trying to work into this, and I did this in a couple different ways that ended up in I think a low key: our democracy is definitely threatened, and I don’t think we should take that lightly. And I’m not even just talking about all the voter suppression stuff. I’m talking about those guys who charged into the Capitol Building Jan. 6 and actually tried to overthrow the democratic process we’ve had in place for the last 230 years, and a lot of people in this country are kind of ho-humming that, like “oh, let’s try to move on and rebuild the census.” Well yeah, let’s try to rebuild the census, but let’s not pretend like that was just a little hiccup.

Nothing like that has ever happened in America before, and it was appalling, and I think it’s an affront to anti-fascists, and I do believe that the men and women who fought in World War Two were the first generation of anti-fascists. You can’t be a person who likes democracy and supports fascism, they’re systems that are diametrically opposed. The guys at Normandy were just that; anti-fascists because they defended democracy. So I wanted to make a statement about how democracy is fragile, and we have a lot of people who are breaking through its guardrails and its traditions, its precedents, as if they are acting in some democratic way, like, “the election was robbed! Stop the steal!” They’ve been propagandized, and they believe these falsehoods that are extremely damaging to democracy. I think it’s an affront to George Fullick and Alfred Gelinas who went off to war thinking, “democracy is at stake here. We were attacked at Pearl Harbor. Look at what these regimes are doing in Europe and Asia: they’re butchering people by the hundred of thousands.” And that’s where fascism ends; that’s what happens, and history shows that. I wanted to make sure that was part of the address. So I did my best to channel Abraham Lincoln and his Gettysburg Address, to say, let’s make sure these men have not died in vain.