Student journalism has been a way to fill local news deserts by reporting on community issues that are difficult for professional journalists to do. Unfortunately, some of the student journalists across the country have been subjected to censorship through school administration or readers.

Currently, 17 states in the U.S. have the New Voices Law enacted. The New Voices Law ensures that student journalism media can only be censored if it is libelous or slanderous and prohibits retaliation against journalism advisors who refuse to censor student media.

In the case of Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier in 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court debated whether or not schools should have the power to censor student news media and limit First Amendment rights of students. The First Amendment protects the freedom of five avenues of expression, including freedom of the press. In the 1988 case, three high school journalists in Missouri sued their school district over an infringement of censoring them for covering divorce and teen pregnancy. The court ruled in favor of the school, as the dissent decided by the supreme court was that schools had the right to monitor and censor certain sensitive topics.

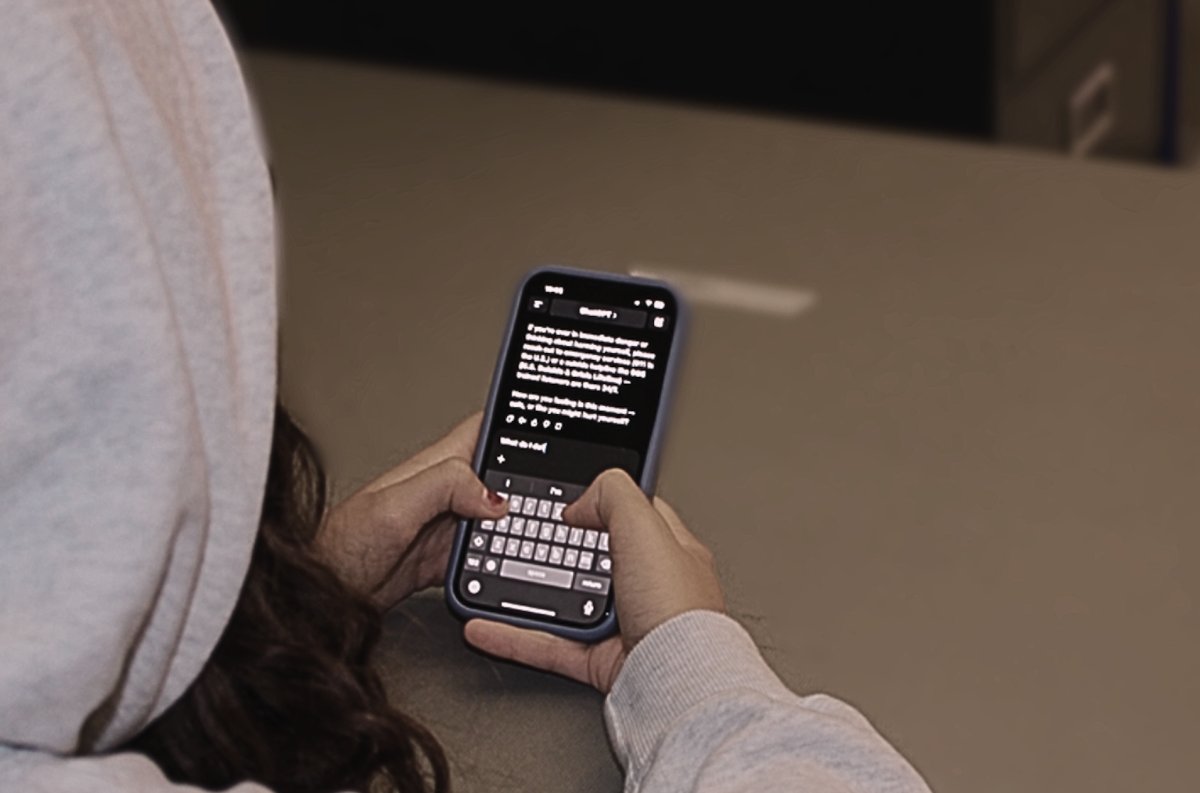

Student media censorship is still very common, with 33 states having no New Voices Law in place. This means that many student-run newspapers’ freedom of speech is limited in journalism. In the academic year of 2016-17, 60% of student editors reported experiencing at least one instance of censorship. In the 2020-21 academic year, the number increased to 63.8%.

The Student Press Law Center (SPLC) is a Non-Profit organization dedicated to legally assisting student journalists when facing student press censorship and other legal issues regarding student journalism. Jonathan Falk, a staff attorney at the SPLC, explained that the process of suing against censorship as a student journalist involves appealing to the hierarchy of education. Student journalists have to appeal to the office of the superintendent and then the board of education in order to file a claim. If administrators censor student journalists, the decision made by administrators can be called into question by the board of education members.

“[Standing up to censorship] requires some bravery,” Falk said. “You’re basically a student telling an adult to their face ‘Thanks but no, thanks. I want to appeal this further.’ And so, that’s one way of [combating censorship]. It’s certainly within the school district, and that’s something I typically encourage students to at least think about, and then execute a plan for appealing.”

Even though the New Voices Law was enacted in California, the SPLC still gets many hotline calls from Californian student journalists. This is mainly because administrators do not know about the New Voices Law or they just do not care.

“Only [student journalists] can step in to self advocate and actually stand up and say ‘This is my right to free speech under the New Voices law and the First Amendment,’” Falk said. “So that’s one reason why it’s important for students to step up for themselves, but it also clears the path for the successive generation of student journalists.”

Falk’s suggestion is that student journalists talk to administration about journalism ethics and the laws behind student press censorship in order to prevent it.

Missouri is one of the several states in the U.S. that doesn’t have the New Voice law. Pathfinder is the student news publication of Parkway West High in Ballwin, Missouri. There have been multiple incidents when their publication has had to take down articles due to censorship.

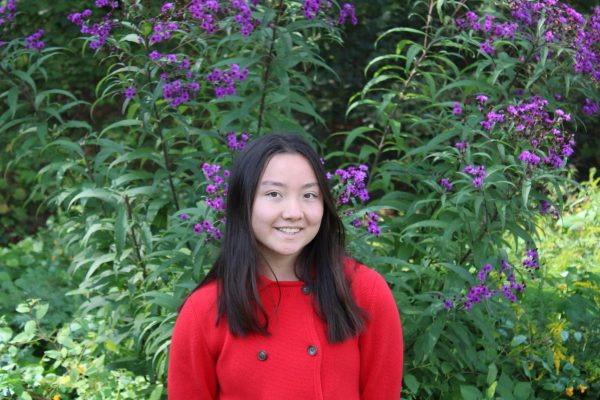

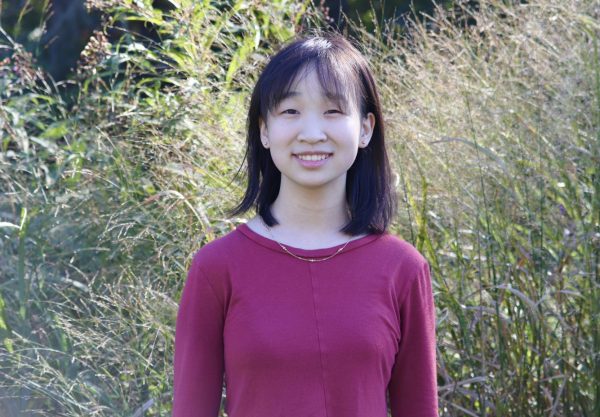

“I think because we’re not guaranteed our right to free press, we have to be a lot more careful about what we publish because we know that our paper and our advisors can face repercussions for what we put out there,” Pathfinder’s Editor-in-Chief senior Serena Liu said.

Junior Risa Cidoni is the features editor at Pathfinder. In her first year as a staff reporter, she wrote a profile on a dancer at her school. When the story was published, the parents of the dancer were angered over a quote their child had said that got published, so eventually the article had to be taken down.

“While we do want to always have our voice heard, without the New Voices Law, it does make it more difficult to be able to stand 100 percent and say, ‘No, I’m keeping this up,’” Cidoni said. “Because if the parents do actually get really upset by [what their kid said in the article], they can take legal action against us. I can understand why we had to [take down the piece] given our circumstances.”

Liu mentioned her and other Pathfinder reporters reported on a school event where non-African American students poorly and inappropriately portrayed African-American culture. The students ended up reaching out to Pathfinder and told them they were upset over the way the article portrayed them.

“We didn’t end up taking that one down,” Liu said. “But we did add and edit to clarify we weren’t trying to call them racist. We were just trying to create a conversation about cultural appropriation there.”

Both Cidoni and Liu are members of New Voices Missouri, which is a group of student journalists advocating for the New Voices Law. In their time with New Voices Missouri, they have sent calls and emails to representatives in Missouri. Efforts to pass the New Voices Law in Missouri have been difficult because it hasn’t been prioritized, but the New Voices Law has been introduced to legislators in Missouri.

“[Censorship has] happened to people in [New Voices Missouri] where other student journalists just had to take articles down,” Cidion said. “I think that [advocating for the New Voices Law] is really important. Especially with a lot of younger writers trying to get their word out, I think it’s super important that we get to be able to write about people’s stories without others invalidating them.”

![Currently only 17 states in the U.S. have a New Voices Law enacted.

“[Standing up to censorship] requires some bravery,” Jonathan Falk, a staff attorney at the Student Press Law Center said. “You're basically a student telling an adult to their face ‘thanks but no, thanks. I want to appeal this further.’ And so that's one way of [combating censorship]."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/image-1.png)