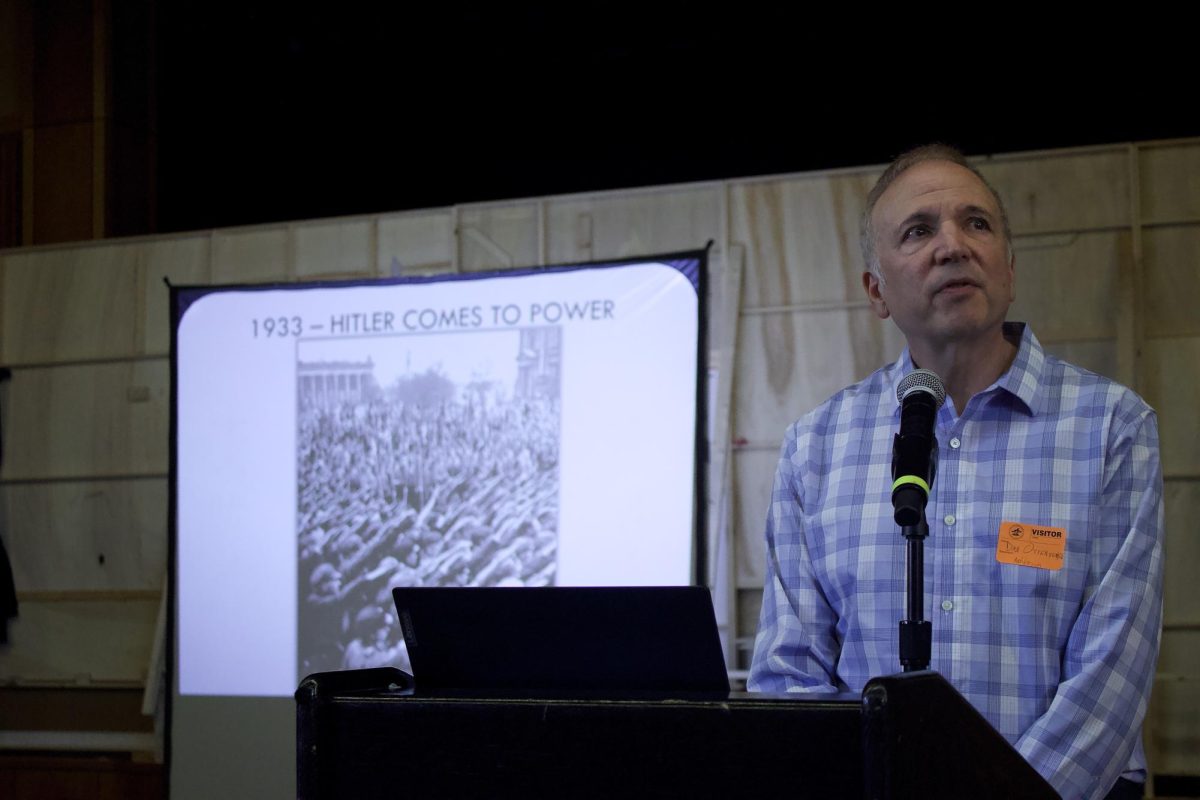

On Thursday, May 8, guest speaker Dan Ottenheimer spoke in the Wayland High School auditorium about his father’s experience as a Holocaust survivor who grew up in Germany during the Nazi rule. He was joined by member of Facing History and Ourselves Jeff Smith as well as a member of the Jewish Student Union and StandWithUs high school program, Alexandra Sinrich.

Ottenheimer grew up in Western Pennsylvania where he had little knowledge of his father’s past. This, however, changed a few years after D. Ottenheimer went to college, when his father became a volunteer speaker at the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh. After his father passed away in 2017 at the age of 92, D. Ottenheimer began to speak in his place to continue the education of the Holocaust by sharing his family’s experiences.

The presentation began with history teacher David Schmirer introducing the speakers and the purpose of the presentation. Afterwards, Smith spoke about his organization, later elaborating on how some people during the 1930s and 1940s acted as perpetrators, bystanders and upstanders. He asked the audience to think about their choices and what kind of choices they would want in their communities.

“People make choices and choices make history,” Smith said.

According to Sinrich, the survivors of the Holocaust carried the trauma and the responsibility to tell the world what happened so that it would never be forgotten. Sinrich then introduced Fritz Ottenhiemer, father of D. Ottenhiemer, and gave details about antisemitism in the modern day.

“Fritz’s story isn’t just about the past, it’s about now,” Sinrich said. “Antisemitism hasn’t disappeared, it’s getting worse.”

The Holocaust and antisemitism now

The Holocaust was the genocide of European Jews and people the Nazi party deemed “unfit for the superior race” from 1933 to 1945. The groups of people directly affected included Jews, disabled people, foreigners, homosexuals and more across all of Europe. To dictator Adolf Hitler, Jews were scapegoats for the problems Germany had faced. During the Holocaust, the Nazis stripped away jobs, property, businesses, basic rights and more. Many were sent to concentration camps where the conditions were inhabitable, causing people to fall ill and die. In total, an estimated 6 million Jews were killed. During this time, while some people helped the Nazis in their regime or turned a blind eye, some helped those in need against the Nazis.

To prevent another genocide from happening, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights was published.

“[The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights] is meant to be a promise to the Lord: never again,” Sinrich said. “Never again would we allow the kind of atrocities that led to the murder of 6 million Jews, people who lost their families, their homes, their lives and their dignity.”

Although the Holocaust is over, anti-semitism is still a persisting problem in today’s society. According to the Anti-Defamation League’s (ADL) 2024 report, 9,354 cases were reported across the country, representing a 344% increase in the last 5 years and a 893% increase over the past 10 years, which is the highest recorded number since ADL began tracking incidents 46 years ago. Even Wayland has had a number of incidentsm, including a spray painting of the symbol of the Nazi’s on the Wayland Community Pool building.

“That’s not just a number,” Sinrich said. “That’s our classmates, our neighbors, our communities.”

Growing up in 1930s Germany

F. Ottenheimer was born in 1925 in Konstanz Germany where he lived with his parents and his sister in an apartment. 2% of Konstanz population was Jewish. F. Ottenheimer lived a normal uninterrupted life, attending school, playing with the neighborhood kids and going to the Synagogue on Fridays.

“In the 1920’s, it really wasn’t that important what your religion was in Germany,” D.Ottenheimer said.

This all changed when F. Ottenheimer turned eight years old in 1933 and Adolf Hitler came to power. They heard propaganda from the Nazi’s all over their town. Radios, newspapers and sound trucks all blasted propaganda, trying to convince everyone that Jews were problematic. Not only was propaganda constant outside of school, but it was also inside of F. Ottenheimers school. There were “race studies” done where students were taught about “the superiority of the Aryan race.” Once a week all students went into the auditorium where they listened to Hitler’s speeches and sang antisemitic songs with lyrics such as “when Jewish blood squirts from the knife, everything is going well.” Some kids also went to Youth Hitler meetings afterschool.

“Imagine what my dad felt like, being in an auditorium filled with kids, and all of them are singing a song about stabbing Jews,” D. Ottenheimer said.

F. Ottenheimer’s dad and mom thought that this would all blow over quickly. However they came to realize they were wrong. They thought that the German people were too well educated, honest and decent to believe the propaganda. However, when their neighbor began wearing a Nazi emblem on the lapel claiming to support the government’s efforts to straighten down the country, they realized that people were blind to everything else but the propaganda about how all Jews were “bad.”

“Many people wound up believing the propaganda was true,” D. Ottenheimer said. “Even though, if they had bothered to look in front of their own lives they could have seen that it was false.”

F. Ottenheimer’s dad, who was a World War One war veteran, owned a clothing store in town. During the Nazi regime, stormtroopers were posted outside of Jewish owned stores to try and intimidate potential shoppers to prevent them from shopping in the stores. Eventually the clothing store was forced to shut down. During this time Jews were banned from sporting events, restaurants, hotels and even park benches.

To try to escape the Nazis, the Ottenheimer family called relatives in the U.S., asking them to sponsor them for immigration to America. In 1936, their applications were sent to the U.S. consulate and put at the back of a waiting list. After two years, their application came up for review and was denied. After contacting their relatives again and getting them to put up a larger financial guarantee, they reapplied for immigration.

“We think that the application was denied because my grandfather during World War I had suffered an injury, and because of that the US officials felt he would not be able to get a job in the United States,” D. Ottenheimer said.

While they were waiting for their verdict, the Night of the Broken Glass – also known as Kristallnacht – happened on Nov. 9, 1938. When this occurred, 13- year-old F. Ottenheimer was awoken in the middle of the night to see the Konstanz Synagogue that his family lived next to blown up by the Schutzstaffel (SS), a major paramilitary organization within the Nazi party. Hours later, police came and took F. Ottenheimer’s father into custody without providing the family any reason.

“My grandmother spent the next several weeks desperately trying to find out what happened to my grandfather,” D. Ottenheimer said. “She and my dad wound up sitting at home, paralyzed, not knowing what was going on or what they could do.”

It was after he came back home that the family found out he was taken to the Dachau political concentration camp, where prisoners were forced to run laps outside in the freezing winter in thin clothes, eat moldy unsanitary food and prisoners died of dysentery. He was at the camp for six weeks and returned home sick and severely underweight, but alive.

“He had lost a tremendous amount of weight, just skin and bones when they opened the door and saw him,” D. Ottenheimer said.

Living in the U.S. and returning to Germany

In 1939, the U.S. consulate approved the Ottenheimer family’s second application, and that May they took a train to France and eventually sailed to New York when F. Ottenheimer was just 14 years old. There in New York, F. Ottenheimer knew no English and stood out next to his American classmates. He was forced to repeat seventh grade. Over the summer, he took an English class where he did well enough that he started to perform much better when he returned to school in the fall.

“I think what really made a difference was when one of the teachers organized a boys versus girls spelling contest, and my dad ended up being the boy in, and all the other boys were cheering him on,” D. Ottenheimer said. “I think that’s what finally broke the ice and made it so he could really fit in.”

In June of 1944, he graduated from high school and enlisted in the U.S. army to help the U.S.’s efforts to defeat Nazi Germany. During his time, he went back to Germany and helped towns that were ruined by the Nazi’s. D. Ottenheimer shared that his father was horrified by what he saw, foreigners and Jews being treated badly and the conditions in the concentration camps.

“He felt like he had a reason to fight back, much more than any of his other high school friends did,” D. Ottenheimer said.

In May of 1945, Nazi Germany finally surrendered but F. Ottenheimer continued his stay in Germany to help de-Nazify the area. However, the war still had a detrimental cost on families all over Europe, including the Ottenheimers. His Aunt Marth, Uncle Leon and Cousin Gigi who lived in France were all killed in an Auschwitz extermination camp.

“[Gigi] was 16 years old on the day she was forced out of her home, onto a train, deported to Auschwitz and murdered by the Nazis on the day she arrived,” D. Ottenheimer said.

Upstanders

Throughout D. Ottenheimers presentation, he put an emphasis on the effects of bystanders in the Holocaust. Bystanders are people who stand on the sidelines that don’t do anything. In the Holocaust, there were a number of people who feared standing up to the Nazi’s because of what they could do.

“My dad used to believe that if more German citizens fought back and protested what was happening, that in fact, it would never have gotten as bad as it did,” D. Ottenheimer said. “He felt one of the worst things about the whole situation was that there were 50 million passive bystanders in Germany.”

However, while there was a population of bystanders that allowed these atrocities to go on, there were also upstanders that stood up against Nazi Germany.

“What studies have shown is that unchecked hatred develops to genocide, and so what upstanders do is check the hatred,” D. Ottenheimer said.

During the Holocaust, the Ottenheimer family were supported by upstanders and were upstanders for other victims. One example of this was when F. Ottenheimers father went to open his store, only to find a Nazi stormtrooper waiting outside. F. Ottenheimer’s father showcased his medals and war scars he received after World War I to the stormtrooper in hopes that he would go away. While his actions alone didn’t drive the storm trooper away, upstanders from their town argued against the stormtrooper and emphasized F. Ottenheimers contributions to the community, eventually making the stormtrooper move.

“That was a week where the people of Konstanz wanted to make a difference and stand up to injustice,” D. Ottenheimer said.

The Ottenheimer family themselves were also upstanders. During their time in Konstanz, Jewish Austrian refugee families would come and stay with them as the Ottenheimers would lead them to a stream where they could illegally cross to Switzerland, where the families could find refuge. Refugees had to have visa and official documentation which few had as they were forced to flee their homes.

“[These families] didn’t have any sort of documentation, they had just grabbed some clothes and ran out of the house,” D. Ottenheimer said.

Another key player that helped the Ottenheimers sneak families into Switzerland was a police inspector who demanded a small fee for his help. The police gave the families official papers to go to Switzerland, and the fee they charged was to pay the taxi to get to the border of Switzerland. That police officer was also an upstander in the Holocaust. While he was just one person, he helped prevent many more lives from being taken.

“This Konstanz police inspector and my dad’s family helped 200-300 Austrian Jews escape into Switzerland,” D. Ottenheimer said.

The idea that upstanders help prevent such tragedies from happening is still relevant in today’s time. By being an upstander, people can stop things from progressing too far before it turns into something to look back on and regret not taking action. If you see something wrong, stand up to it, don’t be a bystander and let things happen that you might be able to control. Some of the Wayland community has participated in protests against racist and antisemitic acts that happened in the town throughout the years.

“I do think anybody’s capable of being an upstander,” Schmirer said. “The reason why it’s so essential now is that the more people that do it, [the more] people stand up. But when the fear is in place and the concern is in place, it makes it just so easy for people to step back and do nothing.”

Why learn and what can we do?

Currently in Wayland, the Holocaust is covered in the ninth grade history curriculum, but why should we educate students about the Holocaust? One reason is that this story not only affected one individual, but it affected families all over the world. Though the Holocaust happened 80 years ago, this genocide has left a permanant mark on people today.

“This is one story of literally over 10 million stories,” Schmirer said. “There are families out there around the world that have suffered and struggled with this.”

Another thing that people should be aware of is that this event was a real tragedy that affected millions of people. It’s not something that people should forget about, but rather something people should be learning from.

“If anything gets taken away from this, it is that students walk out with the awareness that this has happened,” Schmirer said. “It’s not just something in the past, it’s something that we have to work on to make sure that it doesn’t happen now.”

How can we educate ourselves to make sure that this doesn’t happen ever again? People can continue to read about what happened, look at online exhibitions and visit Holocaust museums and memorials.

Continuing to listen to others, stand up and look into different peoples perspectives can help eliminate hate, and prevent another event like the Holocaust from happening.

“It’s by understanding the differences that are there [and having] a greater appreciation and understanding of what those differences are, that’s how you prevent conflicts like this or these types of events from taking place,” Schmirer said. “It’s the lack of connection to others that builds mistrust and makes it so easy to develop resentment [and] hatred.”

![During the WHS club fair, senior Molly Bergeron is watching a student sign up for her club, Eliza J. Norton Foundation. In this club, students meet every week and come up with ideas to spread the message. "[This club] really touches a lot of people in the town," Bergeron said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_1335-1200x800.jpg)