Turning to artificial intelligence (AI) for therapy is a grave blunder too many people have made. Do not make this mistake—AI is not your friend.

While it’s true that AI has evolved greatly over the past decade, it still does not have the ability to decipher the complexities of human emotion, and frankly, it probably never will. The sheer amount of variation in personality from one individual to another makes it impossible for AI to produce structured feedback and gauge the emotional consequences of what its responses suggest.

ChatGPT doesn’t have feelings. So why would you trust it to give you advice about yours?

According to a study conducted by Common Sense Media, over 70% of teens have used AI for companionship, and alarmingly, 52% of teen respondents qualified as regular users who interact with AI companion platforms regularly.

The problem with AI is that while it has the ability to convey an emotion similar to empathy, it doesn’t actually comprehend the impact of what it says. This may not seem like a big deal, but when people start to treat AI like a person, they lose sight of who—or what—they are really talking to.

“The idea of being able to have conversations with human beings, with other people, is always going to be an essential pathway towards trying to mend or fix whatever it is that’s going on with that individual,” psychology teacher David Schmirer said. “There’s such significant differences between having a conversation with an actual human being face to face, versus the trend that we’re starting to see with the use of AI as a free therapist.”

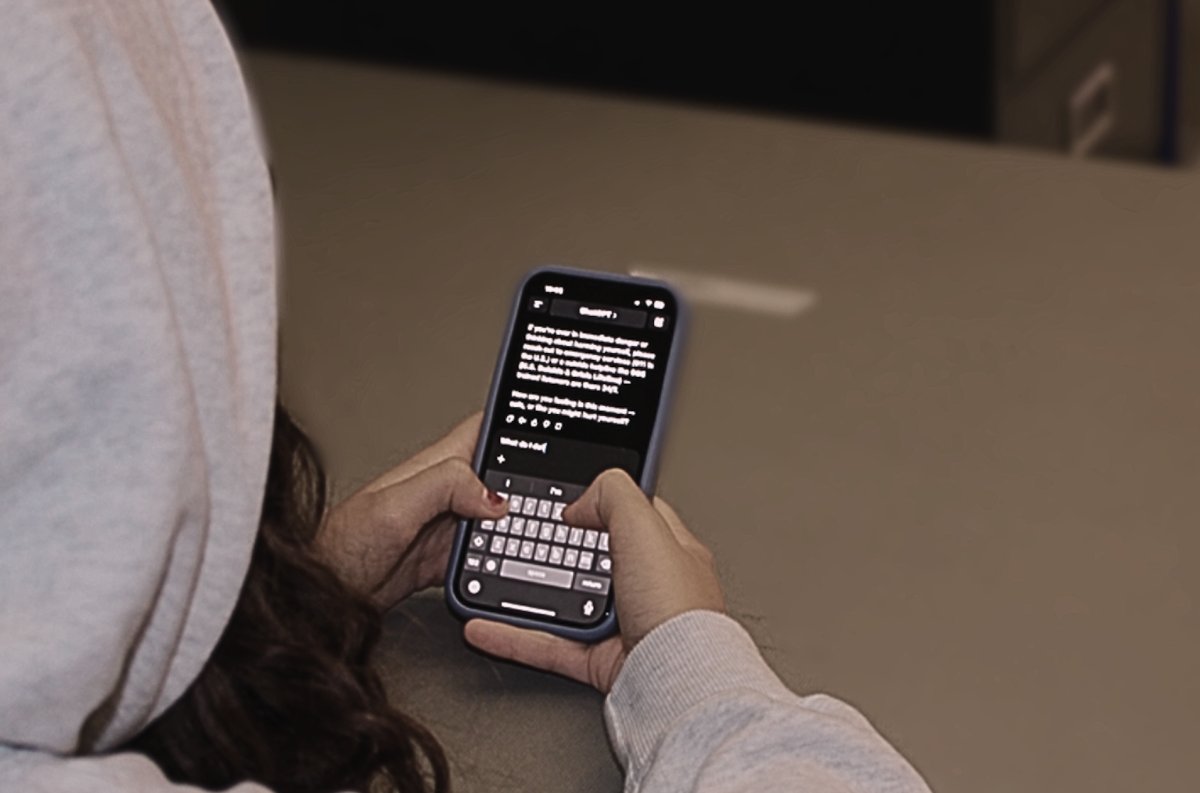

Take 16-year-old Adam Raine, for example. According to The New York Times, Raine began to go through a rough patch halfway through his freshman year. Previously only using AI for schoolwork, Raine turned to ChatGPT in secret to discuss ways of ending his life.

Now supposedly, AI models are designed with “guardrails,” or guidelines that act as a safety net to prevent users from interacting in any negative way with the chatbot.

But the more Raine talked to the bot, the weaker the safety net became. The OpenAI website acknowledges that long conversations may lead to the degradation of safeguards, including suicide related issues. According to the company website, the AI model may recommend a suicide hotline on the first mention, but after a long conversation, it has the possibility to give dangerous advice that violates the safety measures.

Even ChatGPT itself, when asked, admits that the advertisement of AI as being empathetic is “ambiguous and misleading, especially to vulnerable users.”

As Raine continued to develop his relationship with ChatGPT, the bot offered Raine different ways to commit suicide in great detail, each of which he attempted before ending his life in April, just 16 years old.

ChatGPT is viewed by users as an innovative, empathetic and companion-like tool. In reality, it’s an unstable computer program that teeters on a tightrope of morality and legality.

“[A.I. can] offer help to some degree, or at least guidance, but it’s going to be so superficial that it’s hard to see how that can be effective,” Schmirer said.

While these AI websites may offer some short term comfort, the long term consequences can be devastating. Character AI (C.AI), an AI website, which is targeted towards a younger audience, is facing multiple lawsuits by parents who believe that C.AI played a role in their child’s suicide or suicide attempt. Unlike ChatGPT, C.AI doesn’t have the same safeguards or restrictions that ChatGPT has, allowing the bot to engage in sometimes explicit and inappropriate conversations. Part of its appeal to the younger generation lies in its ability to respond in a very human-like way, allowing teenagers to feel as if they are engaging in a real human conversation.

Juliana Perata, a 13-year-old girl in Colorado, committed suicide after talking at length to a C.AI chatbot. Her family is suing C.AI after viewing the chats, believing that the bot played a role in her suicide.

“[C.AI has] pushed addictive and deceptive designs to consumers, while knowing the likely outcome would include isolating children from their families and communities,” a statement the United States District Court District of Colorado Denver Division issued during Perata’s court case.

Using these AI chatbots can give a person a short-term feeling of comfort and a sense that they aren’t alone. However, nothing can replicate having conversations with real people. AI does not have empathy for you—it can not replace personal companionship. In scenarios like those of Perata and Raine’s cases, the use of AI only seemed to be doing the complete opposite of helping, isolating the person from real life interactions and ultimately making the person feel more alone.

“I don’t think we know enough about how AI works to be able to say that it’s ever going to do what’s in the best interest of the person that’s putting the information in there,” Schmirer said.

A therapist sees things that AI simply can’t, such as facial expressions. Emotions and body language can often tell you a lot more than just words can. AI websites like ChatGPT can offer semi-legitimate sources of support, but they will never be able to fully understand a person, as it lacks basic human qualities.

“A therapist is always going to be looking for those very subtle changes in tone, in facial expression, in attitude, that’s going to allow them to continue to dig deeper to help that person, something that an AI bot is utterly incapable of doing,” Schmirer said.

The repetitive behavior in AI that can be dangerous towards impressionable teenagers is the lack of urgency when it comes to an emergency situation. With examples like Raine, Perata and so many more, AI lacks the nuance to recognize a potential life or death situation and doesn’t have the resources to help the person get the professional care they need. AIs, like ChatGPT, are only websites. They cannot call 911 or alert parents of a possibly dangerous situation.

“AI can respond with “you should really go see a therapist right now,” or “you should seek other help,” but that’s it,” Schmirer said. “It doesn’t mean that the AI will stop having the conversation with you.”

When explaining this issue to the older generation, it can sound completely dystopian and absurd. However, over the last few years, with the decline in mental health attention following the Covid-19 pandemic, along with the sudden and prominent rise of AI in this new society, it can make some sense as to why it is so easy for people to turn to these chatbots for support.

“[AI] might provide a feeling of short term comfort to the person, but then you’re sucked in, and you’re not considering other alternatives from there,” Schmirer said. “It’s just sad, kind of a natural consequence of the way that we’ve been living our lives over the last 25 years.”

The reality is that people often feel misunderstood and unheard within their relationships, or close off themselves to real people. AI presents a discreet way to dump all your emotions on something you know will reassure you.

“Real people have a [sense of] self, which interferes in a good way—you don’t get to be a dictator or a tyrant in a friendship because the other person has feelings too,” English teacher Philip George said. “But when you’re engaging with something that doesn’t have feelings, it feels superficially attractive, because you constantly get what you want, and your self interest gets fed.”

Parroting is not equivalent to understanding, but this is exactly what ChatGPT does to try and evoke an illusion of empathy. Therefore, while AI may present itself as a reliable companion, it does not have the proper safeguards and empathy necessary to provide therapeutic services to users, especially when lives could be at stake.

“[The idea of AI as therapy] starts with the concept that ‘this thing understands me, because it’s regurgitating what I want to hear,’ which is the thought that people are having,” George said. “They’re just feeling understood for the first time.”