Check out the other articles and opinions in our K-9 Drug Search series.

Opinion

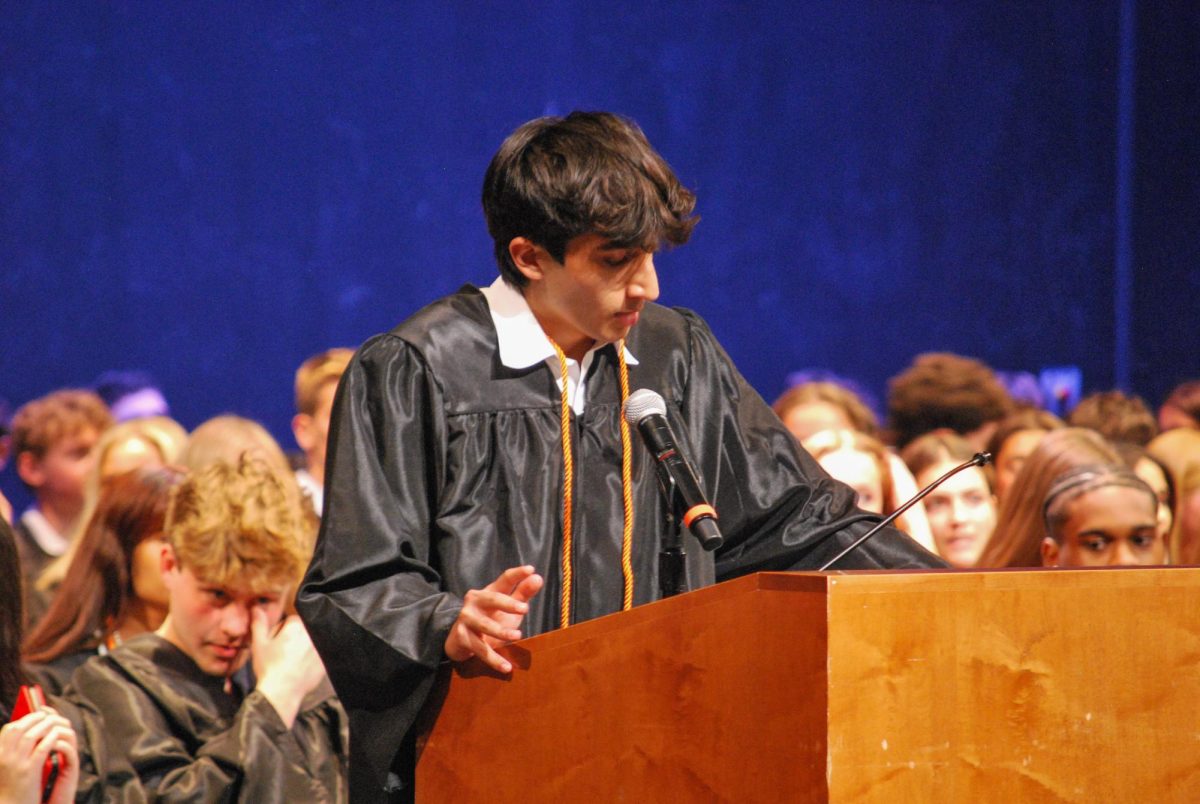

On Friday, December 11th, regional law enforcement executed a k-9 assisted drug search at the request of the administration. Students were placed in a lockdown while over a dozen dogs swept parking lots and a handful of homerooms. No drugs were found, a fact that didn’t surprise many students. The drug search and the date of its execution were secret, so naturally many students knew about the search well in advance.

When WSPN interviewed Principal Patrick Tutwiler, and asked him how he felt about the leak to students, Tutwiler wasn’t phased. “It’s symbolic,” said Tutwiler. “It’s kind of like a state trooper who is sitting on 128, right? You’re going 70 miles an hour. The speed limit’s 65. You see the state trooper, and what do you do? You slow down.”

Tutwiler is drawing an interesting parallel. His intentions to have the drug search serve as a reminder of the rules are clearly represented by the metaphor. However, beyond Tutwiler’s intentions, the metaphor is a poor fit for the actual events that transpired, and the actions of the administration.

The drug search didn’t just slow Wayland High School down a little bit, it brought the entire community to a screeching and abrupt halt. For a little over 20 minutes the entire campus was, to continue the metaphor, pulled over by a state trooper, and searched against their will. The school has full legal right to search students against their will on campus due to the in loco parentis doctrine.

It is the position of the courts in our country that students forfeit a number of their constitutional rights as they cross the threshold onto campus, including their 4th Amendment rights “to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.”

The concept of in loco parentis (a Latin phrase meaning “in place of a parent”) is used by courts to justify and uphold the practice of searches and seizures by public schools. This doctrine allows schools to act as a parent when deemed necessary by administrators. If the acts of students are interfering with education, then the school has the right to suppress those actions.

However, it isn’t the legality of the drug search that should give students pause, it’s the moral message (or lack thereof) that it sends, and the attitude of the administration that should have students concerned.

[adrotate group="2"]

The search represents a paradigm shift in the school’s treatment of students, despite Tutwiler’s true and heartfelt intentions. It shows an either conscious or subconscious belief that students are guilty until proven innocent. Sacrificing the rights of all students in an attempt to pinpoint specific substance users is a poor and rash decision. To return to the state trooper metaphor, it was pulling over every single student, for the suspected speeding of a specific group. It’s a non-attempt to solve a problem.

The search didn’t stop students from “speeding” the second the dogs left. It could possibly have been intended to serve as a deterrent, but I personally was too distracted by the accusatory nature of the search to notice. It’s not the right way, the moral way, or the respectful way to go about dealing with drugs on campus. Most importantly, it’s not the Wayland way. Or I should say it wasn’t.

It’s fair and reasonable for the school to ask students to keep drugs off campus, which Wayland does through part of its student chemical health policy. In loco parentis gives them the legal right, and it seems fair that the school set rules on their own property.

However, extension of that power and influence beyond campus is overstepping boundaries. The newly revised chemical health policy this year does just that, extending its influence beyond campus, clearly prohibiting illegal substance intake anytime, anywhere, and in-front of any other students.

While admittedly off campus drug use has the potential to impact education on-campus, it’s unclear why the school insists on extending its influence when students are off campus. An argument could be made that while students are off campus, no longer in the care of the school, in loco parentis might not apply.

The purpose of a school is to educate students. That education does and should include an education on substances and chemical health. However, educators should not be acting as drug officials. The police should be asking the administration if they can do a drug search on campus, not the other way around. If drug use was such a pressing issue on campus, then local police should have been monitoring the situation, and should have initiated the search. Educators should stick to education, and leave law enforcement up to law enforcement.

Notably silent on the subject of the search are Wayland High School teachers, who possibly should be most upset of all. Nowhere in the faculty handbook are there expectations for staff chemical health. As legal adults, in loco parentis need not apply.

While it is state law that possessing drugs or using drugs on school campus is criminal, teachers aren’t subjected to the same rights-reducing doctrines that allow students to be searched against their will. While the school may be public property, teachers cars were sniffed. Teachers in homerooms selected to be sniffed were either directly or in-directly subjected to the search as well. Hopefully the irony isn’t lost on teachers who teach constitutional rights and George Orwell’s novel 1984 that the same tactics they preach against in the classroom are being used against them.

The concept of “the greater good” has been used by governing bodies since the beginning of time to justify actions based on feeble moral grounds. “The greater good” was justification the U.S. Government used for Japanese internment camps. “The greater good” was also justification used by Nazi Germany for the extermination of millions of Jews.

To be clear, I am in no way saying that the drug search is in any way comparable to either situation, but rather “the greater good” is a poor justification for any action. What’s good for a people is an opinion, and interpretation of what the true “greater good” is will always be subjective.

Intentions don’t justify actions. Ends don’t justify means. In a school where students are taught to think critically about the powers that be, students should feel that their rights were violated; they should feel upset. While the administration had legal grounds to circumvent student rights, the administration lacked moral grounds.

Want to hear other sides of the argument?

Check out the other articles and opinions in our K-9 Drug Search series.

The views of the author don’t necessarily reflect the views of WSPN, Wayland High School, or the Town of Wayland. The opinions in this commentary are strictly the author’s own personal views.

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)

Parent #2 • Jan 10, 2010 at 3:11 PM

While Dave makes a well-considered and well-written point, as a parent, I have to disagree with some of it. It is neither disrespectful nor wrong to attempt to eradicate drugs from a school environment. No one has the right to have drugs at school. And it's the administration's responsibility to act when they know that's happening. The more kids do drugs at school, the more it gets normalized, and the more kids will do it. I want the school to act in loco parentis, and I want to know if my kids are getting high at school so I can get them help while they're still under my roof. And a mere 20 minutes seems pretty quick to get that done.

What I don't get is why the search was done after kids found out about it. That means that only kids who are A) troubled enough to be getting high during school hours and B) stupid enough to leave their stuff around, would get caught. I guess we should be glad we apparently don't have students both that troubled and that dumb. However this seems like a waste of tax-payer dollars to me, and I don't agree that it will keep kids from "speeding." It merely shows them that they can beat the system. I dont see anything wrong with the means — just the ends.