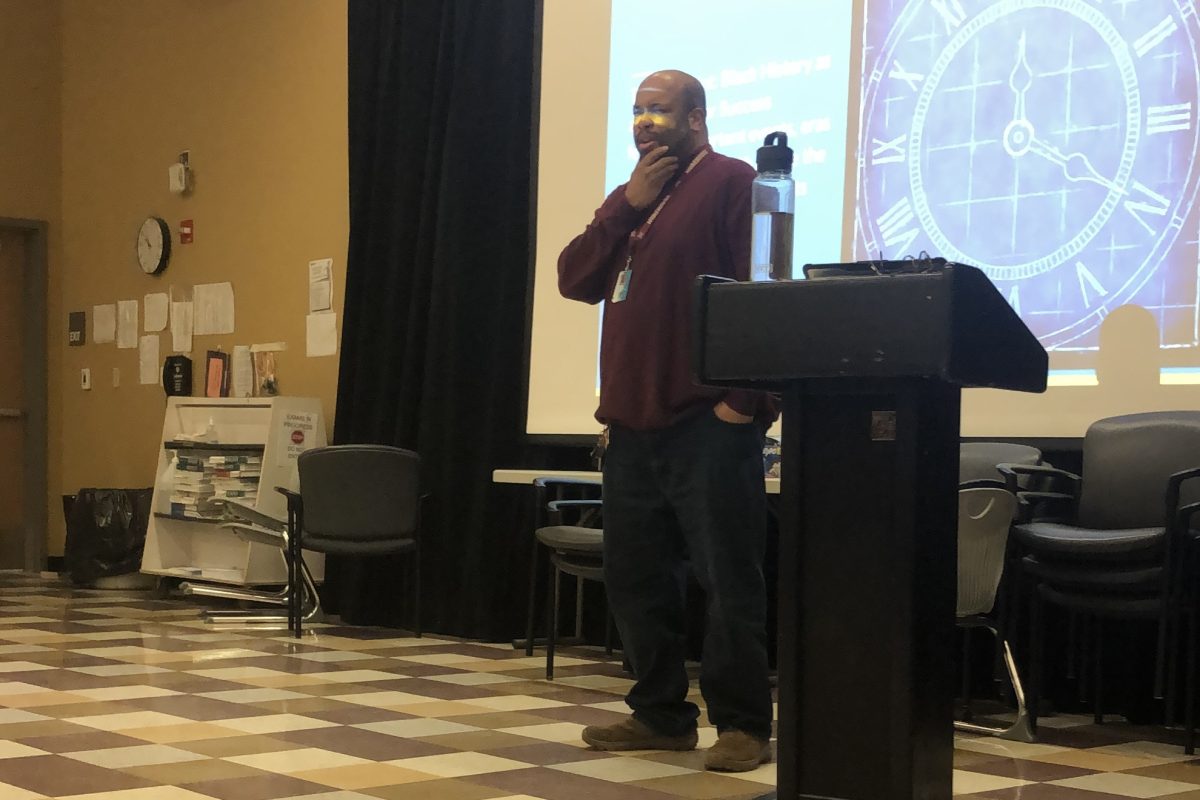

On Wednesday, Jan. 31, METCO coordinator Mark Liddell shared a presentation about the n-word in the Wayland High School Lecture Hall as a Winter Week event. The presentation included personal anecdotes, videos of Black activists talking about the n-word and an opportunity for questions from students.

To begin the presentation, Liddell acknowledged that Wayland lies in the land of the Pawtucket and Massa-adchu-es-et tribes. He shared a picture of a land acknowledgement sign in Grafton, Massachusetts, which he passes everyday on his drive to WHS.

“This land was taken from the indigenous people and it’s bittersweet to see [the sign] every single day,” Liddell said. “I think that whenever there’s a major gathering, we should acknowledge where we are and whose land it was before it was taken.”

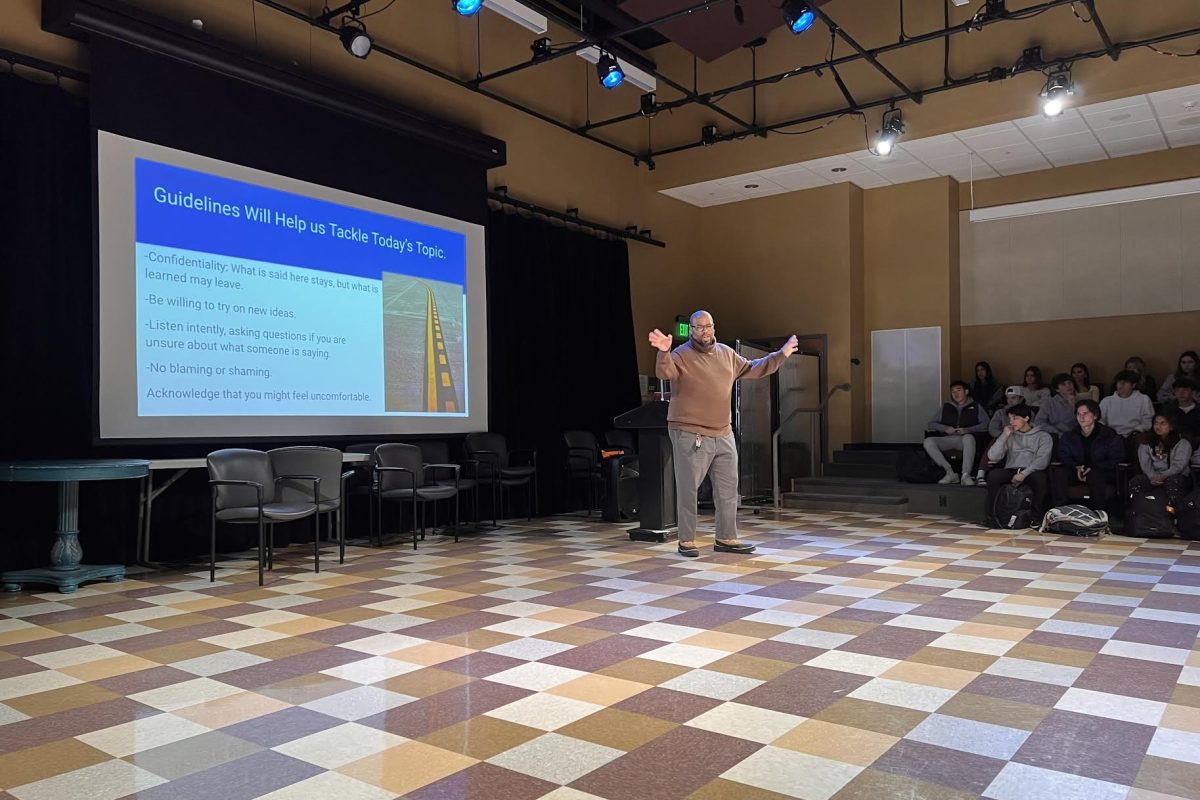

Then, Liddell shared the guidelines of the presentation, which included being willing to try new ideas, acknowledging that students might feel uncomfortable and confidentiality. According to Liddell, the objective of the presentation was to examine the history behind the n-word and its relationship with the value gap, which is the idea that some groups of people have traditionally been valued below the dominant group.

Liddell transitioned into the main topic of his presentation by first discussing the r-word. He explained that the word “redneck” was a term used to describe the sunburnt necks of poor white people who harvested their own crops because they could not afford to buy slaves. Liddell shared an example of something called the “redneck games” in Dublin, Georgia, in which the people participating in the games wear jackets with “redneck” written on them, pants with confederate flags and refer to themselves as “rednecks.”

“They have embraced this idea that they are ‘rednecks,’ they have bought into it,” Liddell said. “These folks are and have been controlled by those who forced that label upon them.”

Similarly to how the r-word was forced on poor white people, Liddell explained how the n-word was and continues to be forced upon Black people in a derogatory way. He described his first encounter with the word, which happened when he was in first grade.

“I was in the playground at school and it was a fifth grade student who approached me and called me the n-word,” Liddell said. “I don’t like the word, I don’t use the word, it’s a word that gets under my skin.”

Liddell also talked about his parents’ history with racism and the n-word. He described how his mother, who grew up in Michigan, once sat down at a restaurant counter, but was forced to leave abruptly because it was not socially “correct” for a Black person to sit at a counter with white people during this time.

His father, who grew up in Mississippi, attended Meharry Medical College in Tennessee where he got his medical degree. When Liddell’s father was traveling by train from Nashville to Mississippi in the mid 1960’s, someone in the white train car fainted and needed medical attention. Even though Liddell’s father was qualified to help the woman, he could not volunteer himself to help because of the repercussions he would have faced as a Black man giving CPR or other medical attention to a white woman.

“I think he believed that if he did help this woman and did mouth-to-mouth, then he would have saved her life but ended his own, so he opted not to help her,” Liddell said.

The stories that Liddell heard from his parents about the racial tension in the early and middle 20th century allowed him to understand how the n-word is negative and cannot be turned positive.

“[My parents] heard the n-word hurled at them on many occasions, and I cannot bring myself to believe that somehow there is a reclamation going on in terms of that word,” Liddell said. “You have to understand [the n-word] in its earlier context.”

Liddell then played a few videos which explained how the n-word has transformed over time. The videos revealed the origins of the word, how it evolved into a derogatory phrase and the negative impact that using the term has on Black people.

“The word has changed and evolved over time, but the word itself is not a word to be celebrated,” Liddell said.

The first video Liddell showed explained both the risk and importance of examining the word, and it went through the history of the word over the years. The second video and third video showed civil rights activists James Balwin and Rev. Al Sharpton respectively as they reflected on racial inequality and their thoughts on the n-word. Then, Liddell played a video of rapper Akala, in which he spoke about the negative effect of using the n-word in songs.

“The use of that word has become dangerous,” Akala said in the video.

Liddell concluded his presentation by inviting the audience to agree that the n-word is hate speech and stating that WHS is a slur-free environment. Liddell believes that “passes” to use this word cannot be given, and he hopes that the audience understands that the n-word cannot be repurposed into a term of endearment. After Liddell finished his final words, he opened the room up for questions.

“I’m hoping that you recognize that the use of the [n-word] is abusive,” Liddell said. “When you see or hear the word, I want you to think about it differently now.”

To see more Winter Week 2024 content, click here.