Exploring the possibility of history curriculum change

October 29, 2014

It was national news. The school board in Jefferson County, Colorado proposed revisions to the history curriculum in their high school, especially the Advanced Placement United States History (APUSH) course. This begs the question: could this happen here?

The Jefferson County school board members proposed to omit topics they believed to be too negative, such as racial conflicts and U.S. expansionism. They believed that the curriculum should be more “patriotic” or pro-American.

Wayland High School’s APUSH teachers and administration think otherwise.

“It was upsetting to me, hearing about these people wanting to review this curriculum and saying that America needed to be portrayed in a certain way, because that’s bad history,” APUSH teacher Katherine Bassen said.

Though she recognizes the concern for the lack of patriotism in American students, Bassen does not see it as her place to enforce that opinion upon them.

“I’m not sure if my job as a history teacher is to make students patriotic,” Bassen said.

Contrary to the school board members, Eva Urban-Hughes, a Wayland High School U.S. History teacher and alumna of Golden High School of the Jefferson County school district, is happy with the current curriculum, believing that it’s better than it was before.

“I no longer have to teach this laundry list of treaties, but rather, I can teach case-studies and create contexts, themes and ideas instead of just stuff that happened, which is useless,” Urban-Hughes said.

Comparing the Jefferson County’s administration and policies to the ones followed here, history department head Kevin Delaney does not believe that history curriculum censorship would happen in Wayland.

“In Wayland, they hire the best people they can get administratively and teacher-wise,” Delaney said. “They don’t quite cut them loose because there’s still curriculum standards, but there’s a lot more deference to the professionals in their respective buildings than evidently there is in this part of Colorado.”

Another major question this event brings up is if, like in Colorado, our own school committee has the ability to alter the curriculum here.

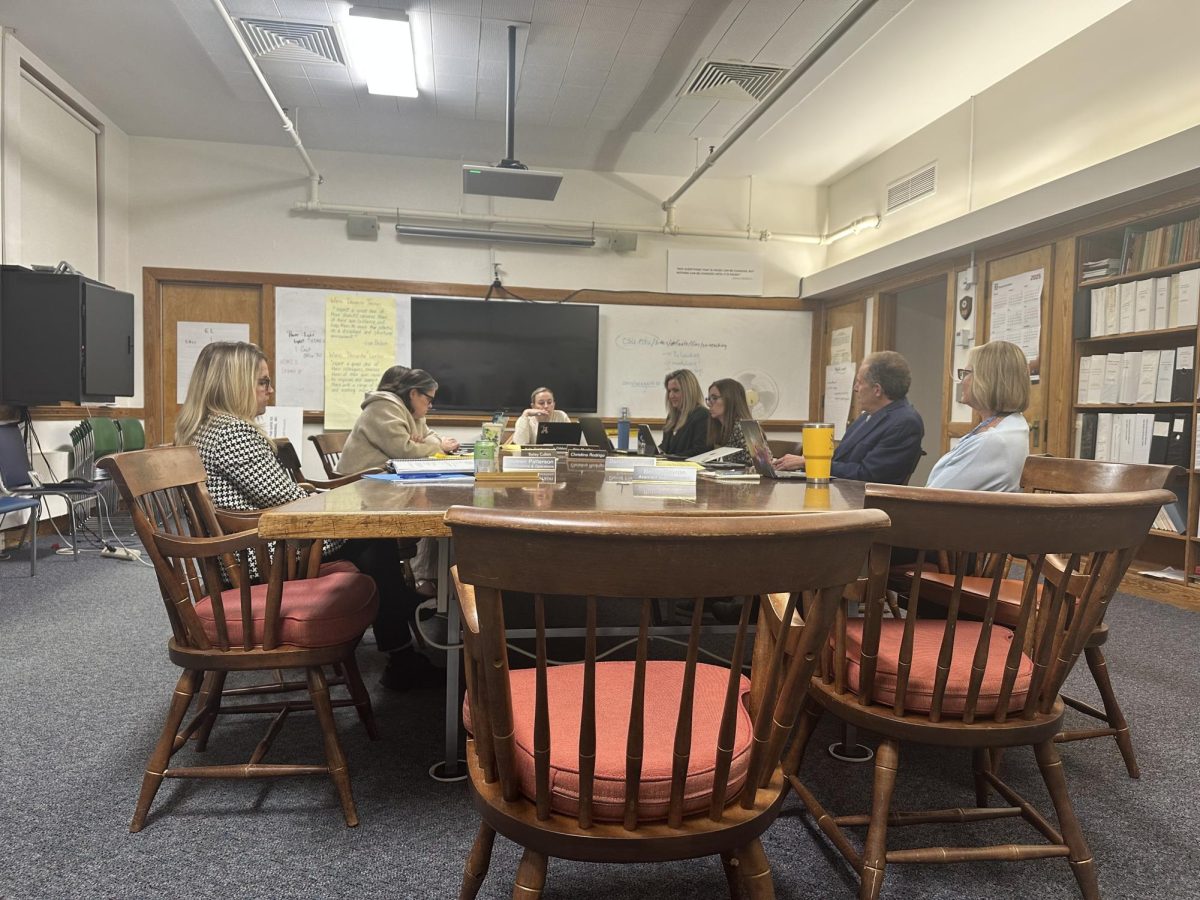

The school board has the power to choose which programs get funded for the school. Superintendent Paul Stein proposes the first school budget, which includes funding for all classes, staffing, programs and any other matters that he thinks the school will need for the following year. Then the school committee steps in to review that budget over the course of five or six months.

“[The school committee] does have the ability to say, ‘We are not going to fund something.’ That is true, but I have not seen that ability exercised in terms of a specific subject matter,” school committee chair Ellen Grieco said. “I have never seen anything like the school committee taking an academic subject and saying, ‘We’re not going to fund that academic subject’ against the will of the the superintendent and the administrators.”

Grieco sees the school committee’s role as a way to further advance the vigor of the curriculum material rather than a way to filter it.

“I would say we have a lot of influence, but I would view it more as a broader level of influence, in terms of the level and the robustness of the curriculum, rather than the specific things that are going to be taught in classes,” Grieco said.

Principal Allyson Mizoguchi thinks that our country’s past mistakes help to build a better future, and the omission of them in history may compromise the integrity of the course.

“If you take the conflict away, you take away the possible lessons that we could learn from them,” Mizoguchi said. “I think we become more informed people that are problem solvers and better citizens when we understand the conflicts in the past.”