Meet the Teacher: Philip Kaplan

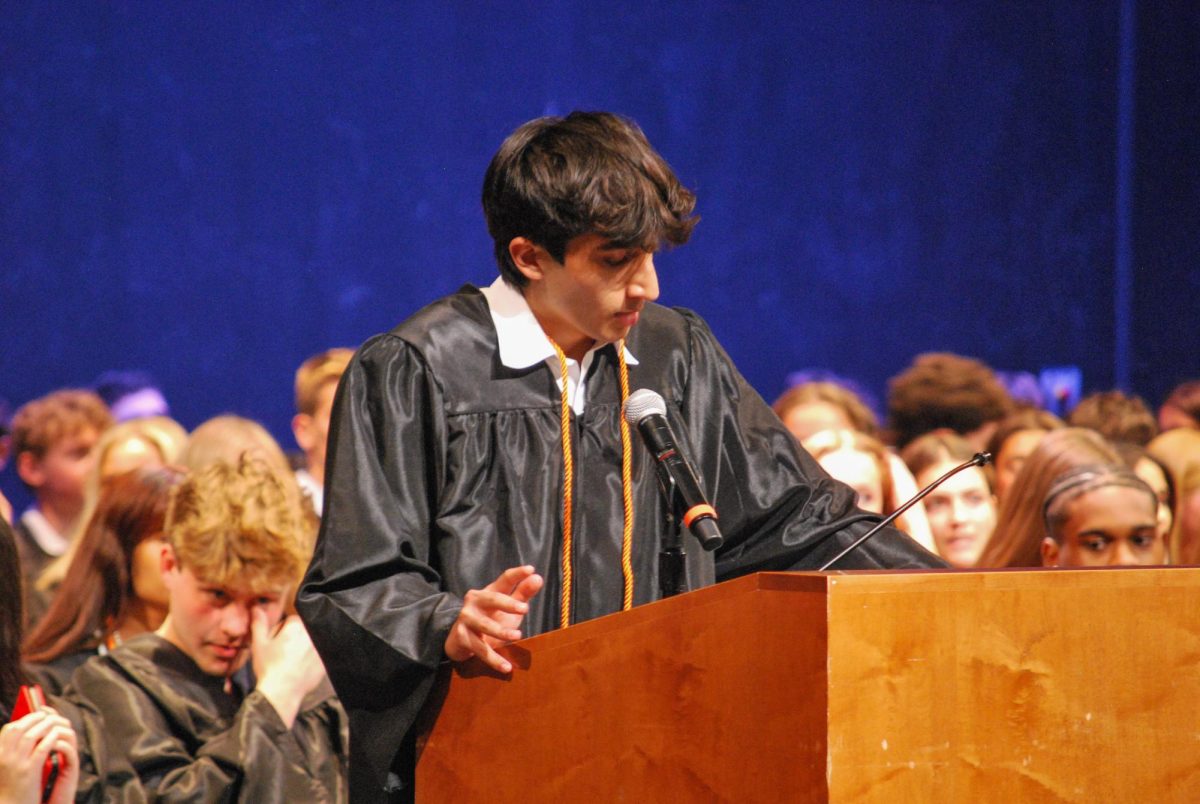

Credit: Nathan Zhao

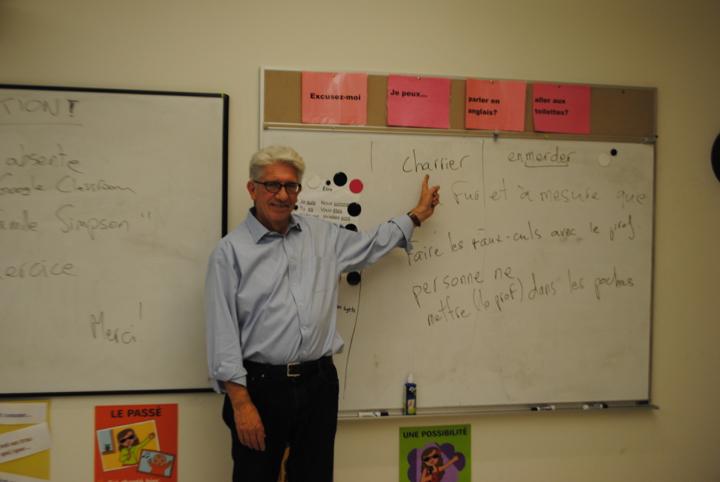

Pictured above is French substitute Philip Kaplan, who will be teaching in place of french teacher Laura Marie until January. “Everybody talks about finding your heart; following your bliss, blah, blah blah. That’s the hardest thing in the world. Do you realize what a gift it is to have that desire? Because without that desire, you’re getting nowhere,” Kaplan said.

October 25, 2017

Philip Kaplan, French long-term substitute for Laura Marie.

What was your job before you came to WHS?

“For the past five years, essentially, I’ve been lucky to get these long-term substitute positions. Last year, for example, I did two: one at Bedford High School and one at Manchester-Essex. Once again, high school French for various levels. I also taught middle school French at North Andover. Also, I’m a professional musician. [So], it’s been a while now since I’ve actually been employed. I’m kind of a freelance.”

How did you get into the business of being a long-term French sub?

“I was very dissatisfied with my previous job, which I had been doing for 25+ years. There was a combination of a burnout factor and the fact that I was unhappy about the way the industry was going. All along, of course, I’ve been a musician. But, it’s very hard to pay the bills as a full-time artist of any kind and for a musician in particular.”

How did you get involved in French?

“I was born in Paris. I grew up there. I grew up bilingual; I was very fortunate. I came to the [United] States to go to college, but since then I’ve embraced my adoptive country. I’ve loved being here very much, but I’ve always maintained a deep emotional connection to the motherland– namely, France. At the point at which I felt I needed a shift in career focus, it dawned on me: I speak a second language, I like working with people, I like teaching; why not teach French?”

What job did you have before?

“I worked in the mortgage industry. I was a mortgage rep.”

How is the French learning environment at WHS different from that of other schools?

“It is very different. From a purely technological standpoint, Wayland is the most advanced system that I [have taught at]. I don’t pretend to be a seasoned veteran, but even Manchester-Essex, which, resource-wise one would think is on par with Wayland, can’t hold a cannon to what [WHS has]. The more important difference here is the emphasis on practical application above everything. There’s a concurrent de-emphasis on too much grammar or on an academic approach to the language, which frankly, is an adjustment for me because I’ve always come at it from the other side. So, I’m still finding my sea legs within this curriculum philosophy that [WHS has]. I like it; it’s great, but there has been a learning curve.”

Do you like this type of practical application-learning basis better than a traditional learning basis?

“There are good and bad points to this learning philosophy. It requires that the students speak up more, both figuratively and literally. The question, though, is how to say something, or if [a student] is saying it very incorrectly. There’s value in just jumping off the deep end and putting yourself out there, okay, that’s not to be discounted, but particularly with French and particularly with the way that I was brought up, French is really about what we call ‘elegance of expression’: the well-chosen words or the well-built phrase. To get to that, [students] need the scaffolding. There’s kind of this tug-of-war going on between the two approaches.”

How do you think these two different types of learning focuses are received by the student?

“At the end of the day, what does [a student] want out of French class to begin with? For those [students] who are there because they, more or less, want to be there, they are aiming to be able to make their way were they to be dropped onto some French street. They hope that they would be able to ask directions about where the nearest restaurant is, or what have you. From that perspective, yes, [one doesn’t] need to have perfect diction or perfect elegance of expression; [a student] just wants to be able to ask questions and reply to questions without getting all tripped up.”

Do you think there should be a cultural emphasis in learning the language?

“I do. That’s where my interests lie. The fact of the matter is that Americans, and I don’t mean this to be mean or critical, but Americans, for all of their reach around the globe, for all of their economic power, Americans are some of the most parochial people on the planet. Now, there’s a good reason for that. There are two main reasons for that. The first is that we have everything we need here. The second is that, all of us, all of the groups to which we belong that have come here, since the very first big waves of [immigration of] the nineteenth century, have come because we were getting away from something. We heard it was in the air, oh, there’s this country that’s a golden land, and if you can just make it there, you can make it. If you work hard and play by the rules. Concurrently, there’s a situation back home that is intolerable or at least bad enough that we have to get the heck out of it. So when you get here, your life is starting fresh. There’s a lot you’d rather forget about what you just got yourself out of. I’ve thought a lot about it; how is it. When I grew up in France, even as middle schoolers, we were aware of what was going on elsewhere in Europe and elsewhere in the world. Somehow it was a parcel of our daily discourse. But you don’t have that here. So, it seems to me that if [a student is] not interested in learning the language and learning the language (and why should they be), then it’s an opportunity to understand and experience, if only vicariously, what a completely different culture is like. That’s what I hope to bring. Yes, we need to buckle down and learn how to put sentences together, but I hope to also give my [students] a flavor of what it’s like to be a French person. The short answer is yes, culture, at least to me, is really important.”

How important is it for students to learn a second language?

“I have to be honest; I don’t see why. It’s frankly an unnecessary addition of stress to school kids’ overall workload. For those kids that are truly interested in learning another language, and in my book, it’s not just “another language,” there’s a specific language. Maybe there’s something you’ve experienced–a movie you saw or a book you read that says ‘French culture; French themes are pretty cool.’ I’m a firm believer that the teacher is called to the student–it’s not the other way around. If there’s something you want to learn, you’re really only going to learn it well if there’s something in you. It’s like an instrument. Should everyone learn an instrument in school? Now, there are certain basics that everyone has to learn: reading, writing, arithmetic, fine. But beyond that, what does it take to find your path of success and contentment in life? It can’t be placed in you.”

How about any exposure to a second language?

“I don’t see the point in forcing someone. Some students don’t have the slightest interest in French, and they take the class just because they want to maintain their GPA, because they want as many options as possible to get into college. That’s fine, there’s nothing wrong with any of that, but I just don’t see the point. It’s so hard to learn a foreign language. All you’ve got is 45 or 50 minutes, and it’s forgotten for the rest of the day except for half an hour of homework later in the night. Again, it’s like an instrument. You’re not going to make any progress, let alone get good, unless you really apply yourself. I got my Bachelor’s of Music from New England Conservatory in classical guitar. How can you do that if you don’t practice two to four hours a day, which is, for most people, ludicrous.”

Do you think it’s still important for students to “make time” to learn a language, just like an instrument?

“The time element is interesting, because if you’re really into something, you make time. Everybody talks about finding your heart; following your bliss, blah, blah blah. That’s the hardest thing in the world. Do you realize what a gift it is to have that desire? Because without that desire, you’re getting nowhere. But did anyone plant that desire in you? I don’t think so. Where did it come from? I don’t know. I don’t want to get religious about it. I don’t want to get spiritual. But it’s a question that I ponder constantly. Because when you’re standing in front of 20 kids and you know that three-quarters of those kids wish, for perfectly good reasons, that they were elsewhere, how do you get people engaged? I can give you stuff to do and scientifically have you do it, but beyond that if I know that you’re just not into it… it’s a deep question that I don’t have the answer to. It’s something that I ponder.”

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)