Opinion: The college admissions scandal is unfair, but not unexpected

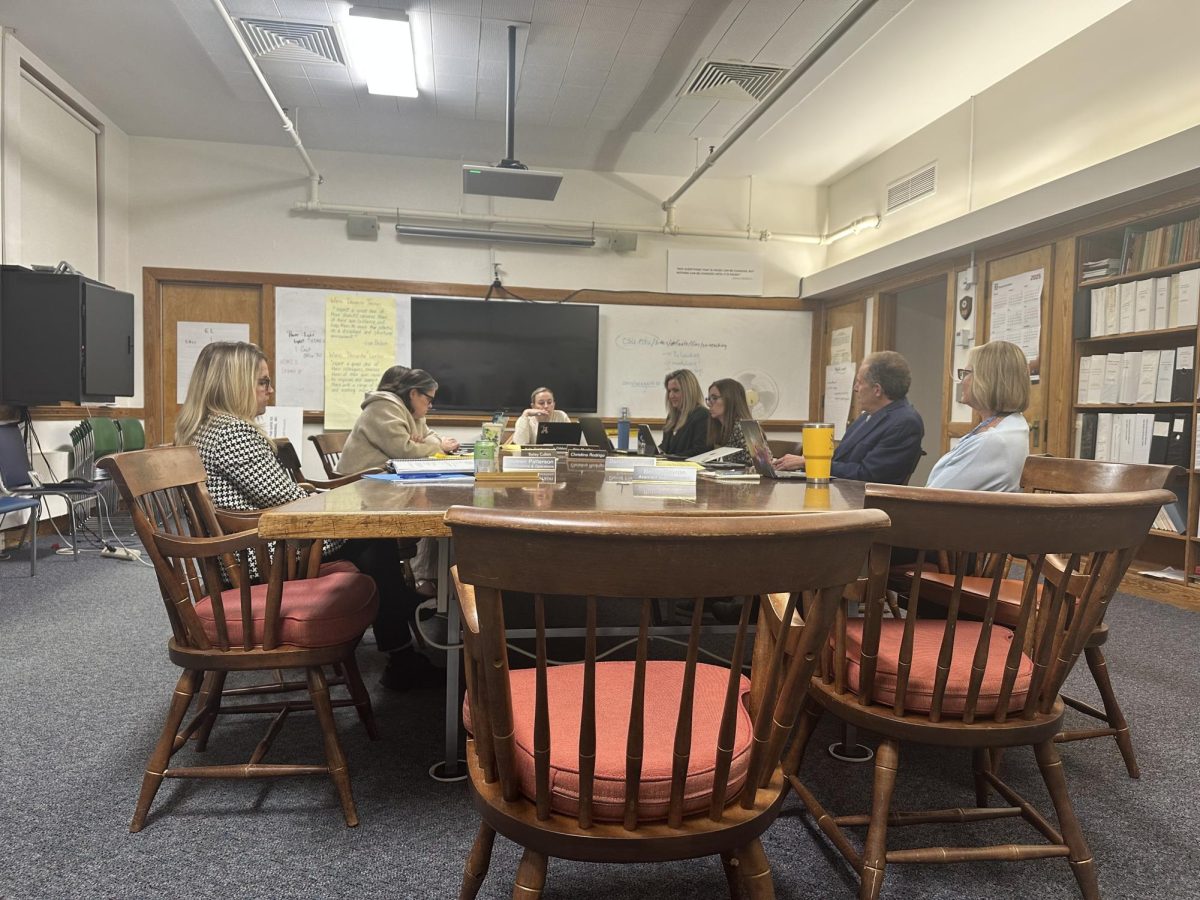

Credit: University of Southern California (USC), Los Angeles, California; Ken Lund

Pictured above is the University of Southern California. Influential Youtuber and social media presence Olivia Jade Giannulli was admitted to USC after her family placed bribes with the crew team to illegitimately list Giannulli as a recruited athlete.

March 29, 2019

For many high school students across the country, the college admissions journey is a time-consuming and stressful process in which students set themselves up in the best way possible to market themselves to top colleges. For a select wealthy few, however, guaranteed admission to a prestigious university simply involved slipping some bribes to a college consultant, who then spread the wealth around to nearly guarantee an applicant’s admission to a specific school.

On March 12, federal prosecutors based in Boston charged 50 people who were involved in this scandal. Wealthy parents paid Rick Singer, a so-called “college admissions counselor,” to spread money around to bribe athletic coaches, fake standardized test scores and instruct them on how to give their kids an unfair edge in getting into competitive schools.

This case of admissions fraud can be split up into two ways: bribery and cheating.

First, Singer took the money that parents paid him, laundered it and used it to bribe collegiate athletic coaches. These coaches then put the applicant on their list as a recruited athlete. This gave them a leg up in the admissions process because recruited athletes are admitted through an entirely different process than typical applicants. Singer went so far as to photoshop faces of applicants onto the bodies of athletes to make their application seem more realistic.

Second, Singer helped students and their parents cheat on their standardized tests such as the SAT or ACT. Singer told parents to claim that their students had learning disabilities so they could gain an edge while testing. This would allow the student to test in a room with only one proctor, or get extra time, for example.

Singer also told the parents to register their students to take the exam at one of two test centers in the country that he “controlled”. Parents could pay Singer to have a proctor lead their student to the right answer in a test, double check their work after the test finishes or even have a stand-in take the test for them.

Just like many other college applicants around the country, upon hearing news of the scandal, I was horrified. I quickly thought to myself, “No fair!” and “This shouldn’t have happened!” These parents exploited their lofty socioeconomic statuses, while dragging their kids behind them, to wrestle their way to the front of the line of college admissions.

What’s more, these kids don’t even need to go to college. The students who didn’t make the cut due to the fraudulent activities of the wealthy worked hard throughout their high school careers to put themselves in a place where they could receive a degree to become more financially stable in the future. Olivia Jade Giannulli, one of the students involved in the scandal, already was financially stable. Before news of the scandal broke out, Giannulli had multiple sponsorships from big corporations, like Sephora and Amazon. Not only did Giannulli not need to be at school, but she also didn’t even want to be there. Giannulli was also criticized for saying she “doesn’t really care about school” and she was at college only for “game days [and] partying”.

On the other hand, while the college admissions scandal is upsetting, it isn’t entirely unexpected. Wealthy Americans have been exerting both their influence and their wealth to streamline their children’s admissions into prestigious institutions for years.

Not to say that bribery and fraud of this kind have been going on for a very long time. This scheme dates back to 2011. The type of influence on admissions that I’m referring to includes elite college counseling and donations. Unlike the scheme that has just recently been unearthed, these practices are entirely legal.

Wealthy parents are able to afford to pay for elite college consultants that steer their kids in the right direction. These counselors help students pick the right extra-curricular activities, sports and classes from an early age so that they can stand out from the rest of the applicant pool. They also help prepare students for standardized tests in a legal way – giving them practice tests and offering private tutoring – all for a price the average family can’t afford.

Another legal way that wealthy families influence college admissions is by actively donating to a school. Funding a library or an academic building is very expensive, and colleges will take notice if a certain name appears on their list of donors more often than not.

Ultimately, the college admissions process is all about making your application stand out when the admissions officer is reading it. If you are partaking in unique and genuine extra-curricular activities and sports and have a very competitive SAT score due to an elite college consultant, your name will stand out to an admissions officer. If your family is a frequent donor and gives a lot of money to a college, your name will stand out to an admissions officer from that college.

While these types of influence are definitely unfair, they are entirely legal. The wealthy few have been exerting their influence on college admissions for years to the detriment of the qualified and underprivileged many.

College can be described by many as a financial investment. Those with a 4-year bachelor’s degree can earn up to 84% more than someone with just a high school diploma over their lifetime. Children of lower and middle-class families who are looking to financially better themselves need every edge they can get when it comes to college admissions, and unfortunately, the rich have been maintaining a monopoly over the process that can change lives for students and their families for generations.

Opinion articles written by staff members represent their personal views. The opinions expressed do not necessarily represent WSPN as a publication.

yeah boiii • Mar 31, 2019 at 9:47 PM

nice article janoff

btw, did tufts like their new boathouse?