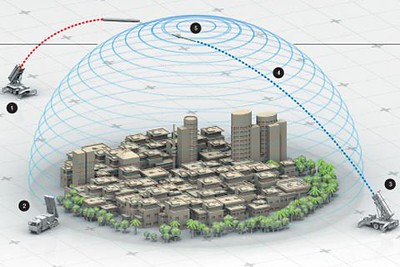

Wayland’s Iron Dome

Pictured above is the “Iron Dome” in Israel, a missile defense system designed to shield the nation from ballistics. Many in Wayland, however, believe that a similar invisible barrier isolates Wayland from other towns and peoples. “We are socially isolated because we are in our bubble, sheltered away from the problems that other towns face,” junior Ethan Betancourt said.

Politicians often speak of bridging the divide between the suburbs and the cities, the wealthy and the poor, the white and the black. Different types of isolation that certain towns or even schools encounter can vary from social to academic issues. A town can become exposed to these issues due to population size, location and the people who reside there.

Some Wayland residents and WHS community members believe that Wayland is generally isolated from surrounding towns across the country or even the state due to these factors. While WHS generally gives their students and faculty more freedom compared to other public schools, it doesn’t stray from the idea that many believe this town seems to live in its own bubble.

WHS is a public school with 846 students that is 30 minutes outside the city of Boston. English teacher Sara Snow describes WHS as having more private school attributes than other public schools.

“I think WHS is more like a private school, so I often think it’s rather like a school down the road called BB&N, [or Buckingham Browne & Nichols],” Snow said. “It’s small enough that every kid is known in the same way that kids in private school are known, and that both has advantages and disadvantages.”

Snow believes that how close or far a town is from an urban center can determine how isolated that town will be. Snow considers the towns that are located outside of Route 128 are to be living within a bubble.

“It’s urban centers that [give] you a sense of what’s going on, and so the further away you get from an urban center, the more isolated I think people become and the less involved they are in politics, culture, society, theatre, music [and] clubs,” Snow said.

Junior Arden Knapp claims that it is actually frowned upon to interact with those outside of Wayland, but she maintains that this trend doesn’t stay with students past high school.

In a WSPN survey of 284 WHS students, 73.9% responded that they believed Wayland is socially isolated from other schools nationwide. Junior Ethan Betancourt concurs with the majority.

“We are socially isolated because we are in our bubble, sheltered away from the problems that other towns face [such as] drugs and crime,” Betancourt said. “[I think we interact] with some people [from other towns], not everybody though. Some people have a life outside of Wayland, whereas a lot of the people in Wayland, most of their life revolves around the town and being inside of it.”

One major aspect of social involvement is the ability to connect with those outside of the town and their imminent communities. Snow often finds herself asking her students what they did on the weekend, and the response is almost always the same: “Nothing.”

Snow believes that Wayland as a community needs to start opening itself up to more ideas of activities that Wayland can partake in instead of doing the bare minimum.

“Wayland is a really sporty school, [so] why don’t we go and see a Harvard lacrosse game? You can see excellent lacrosse for $5 just down the Mass Pike,” Snow said. “I think we need to start thinking a little bit out of the box because there’s so much there, so much fun to be had. I get really depressed on a Monday morning when I say to my kids, ‘So what did you do on the weekend?’ and they didn’t even go see a movie. Like, why [not]?”

Junior Josh Ellenbogen has a slightly different take than the majority. Ellenbogen agrees that Wayland students live in a bubble, but he also argues that this is no different from many other schools and towns in the country.

Edmund DeHoratius, a Latin and English teacher, believes that the social isolation that Wayland faces is primarily caused by the lack of transportation and infrastructure between Boston and its suburbs. The town of Wayland does not offer public transportation, so a Wayland student needs to drive to places like Riverside or Newton to access Metro Boston facilities, making it more difficult to travel.

“It’s difficult to sort of get outside of Wayland because there isn’t a lot of infrastructure that facilitates that,” DeHoratius said. “I think that certainly contributes to [isolation]. The harder it is to get out, the less you want to do it [because of] the more work it requires to do it, and then that just becomes a vicious cycle. So then you don’t go out. You stay in Wayland, and then everything just propagates itself because you don’t want to get out, and then you can’t get out.”

Senior Brian Carmichael agrees with DeHoratius in that contact with other Boston suburbs is difficult for Wayland students. Carmichael, however, is in concordance with Ellenbogen and Knapp that this social isolation doesn’t spread to WHS students’ college days.

Although DeHoratius mentions that the lack of infrastructure generally restricts WHS students from metropolitan Boston, he notes that WHS itself allows for far more freedom.

“I would say Wayland’s best quality is the autonomy and the freedom that students have, and teachers have it as well,” DeHoratius said. “We are able to do a lot of things [on our own] where [at] a lot of other schools, you’d have to check with [the] administration, [and the] administration might say no.”

68.7% of surveyed WHS students agree with DeHoratius that WHS students are given more freedom during the school day compared to students at other schools. DeHoratius details those relatively unique freedoms as an open campus policy for seniors, free periods and the lack of substitutes. DeHoratius attributes WHS’ ability to handle such unstructured time to culture of trust.

“The remarkable thing about Wayland that I’ve learned having taught here now for 20 years is that the culture here makes [the freedom] work. There’s lot of trust here,” DeHoratius said. “That freedom is obviously born of trust whereby implicitly or explicitly, and the teachers [and] the administration trust the students to not abuse that [freedom].”

Approximately 70% of surveyed WHS students would say that Wayland’s affluent status and/or its high school’s small enrollment size contribute significantly to the social culture at WHS. 41% and 30% would say the same about WHS’ general political views and racial demographics, respectively.

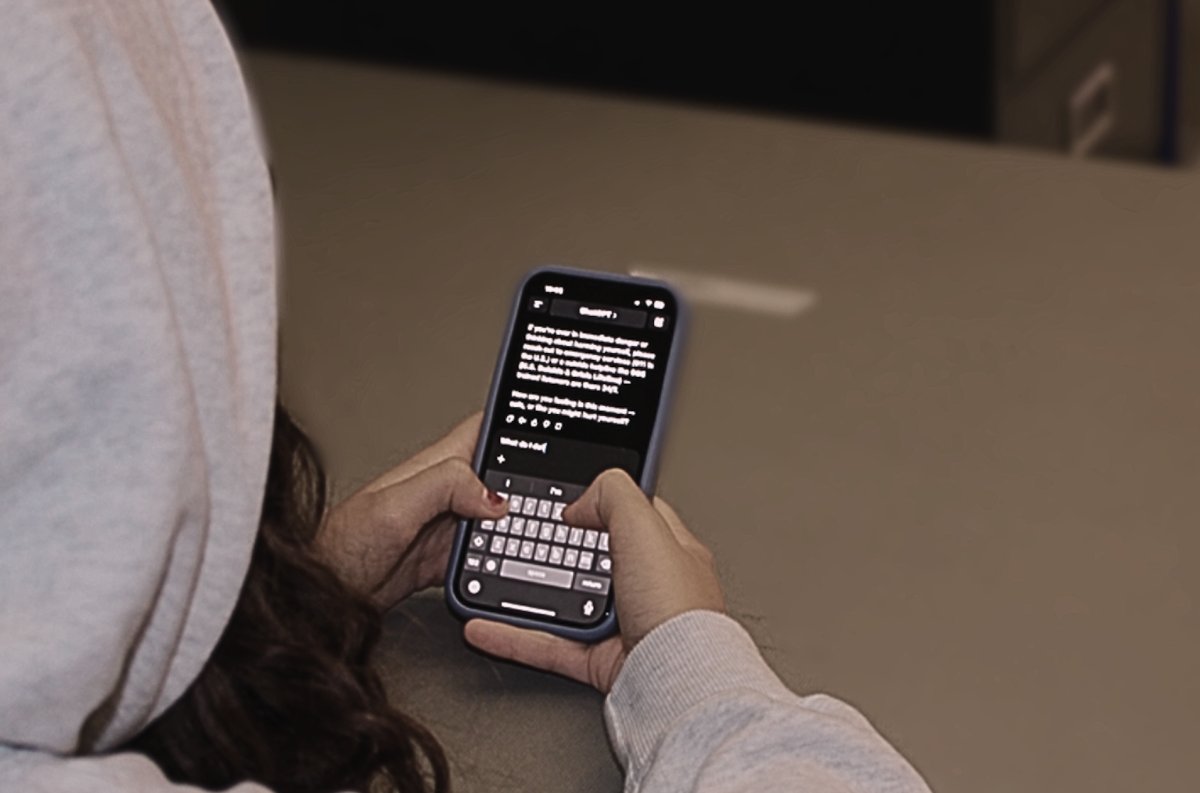

Beyond infrastructure problems, DeHoratius believes that Wayland’s isolation stems from not only a lack of physical exposure but social exposure as well.

“Wayland is a relatively homogeneous sort of place,” DeHoratius said. “That always contributes to this sense of isolation or lack of perspective. We might say it is harder to see things from other people’s perspectives when you don’t actually see those people. The people around you lead relatively similar lives, and so it becomes difficult to get past all of those relatively similar lives.”

82.4% of surveyed WHS students would agree with DeHoratius that over 70% of all WHS students lead very similar lives. This “stock Wayland life” varies from perception to perception, but Snow describes the majority of WHS students as “very well brought up, well educated, polite, kind, relatively stressed and also very individualistic.”

Ultimately, DeHoratius states that he’d like for Wayland to become less socially isolated, but he points out the difficulty in finding effective ways to make that manifest.

“[Social isolation in suburbs is] so prevalent that it’s just a difficult thing to change,” DeHoratius said.

On another note, isolation in Wayland does not limit itself to social issues – academically, Wayland differs from both its state and national counterparts as well.

“Wayland is a pretty typical and impressive high-performing school,” DeHoratius said.

According to 2019 Niche rankings, Wayland is ranked as the 116th best public high school in America and the fifth best in Massachusetts, trailing behind only the Mass Academy of Math & Science in Worcester, Lexington High School, Boston Latin School and Brookline High School.

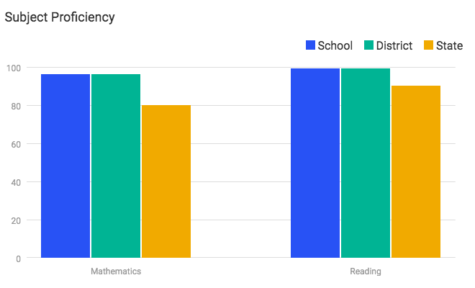

In terms of standardized testing, 96.1% of surveyed students believe that Wayland performs better than most other schools. US News data confirms this, finding that Wayland performs 16% better at mathematics and nine percent better at reading than other schools within the state. Nationwide, US News finds that 59% of WHS students take AP Tests, with 93% of them passing.

Some of this academic excellence can be attributed to the facilities and resources available at WHS and within the general area. These resources can range from test prep, tutors, 1:1 computers or simply the financial availability to participate in standardized testing such as the SAT or ACT. DeHoratius, however, believes that WHS students generally fail to appreciate the fortuity of their academic situation.

“Wayland [students] tend to take a lot of things for granted that not a lot of students or plenty of other students don’t take for granted,” DeHoratius said.

DeHoratius furthers that the resources mentioned above are so abundant and prominent that they become a fact of academic life and not an accessory to their basic education.

“[Wayland students] just assume that they’ll sit down for a standardized test, they’ll get some sort of tutor [and] they’ll get some sort of extra help.”

53.2% of surveyed students agree with DeHoratius that WHS students do not show gratitude for the opportunities they are given, whereas 44% would disagree and 8% believe that Wayland is not academically advantaged with resources at all.

Just like with social isolation, DeHoratius recognizes academic isolation should be diminished in prevalence, but he believes that it is unlikely that WHS can significantly change in this issue.

“I think what you’d [be] flirting with is something on the socialism spectrum where the affluent take what they have and distribute it among those that don’t have such things,” DeHoratius said.

Ultimately, DeHoratius believes that awareness is the most realistic way to work toward a solution.

“Awareness is how [a solution] starts,” DeHoratius said. “I think the easiest way to create that is simply [through] conversations. To see it through someone else’s eyes [is important] because everything is always abstracted. Everything in the news or on TV is always sort of the abstract. I think any time you can humanize that, put a face to it, you realize that they’re the same as you. They have the same worries and the same concerns.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Wayland High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, cover our annual website hosting costs and sponsor admission and traveling costs for the annual JEA journalism convention.

Kevin Wang, Class of 2020, is an editor-in-chief of WSPN, and this is his fourth year on the staff. He is captain of Wayland’s Speech & Debate team,...

Christina Taxiarchis, Class of 2020, is the arts & entertainment section editor for WSPN, and this is her third year on the staff. She is on the Wayland...

Carly Camphausen, class of 2020, is a second year reporter for WSPN. Outside of school, she enjoys playing soccer, basketball and lacrosse. She also likes...