Andrea Shang: If you lose, you have to tell yourself, ‘I can get better’

September 16, 2019

Junior Andrea Shang steps onto the fencing strip, readjusting her lamé and pulling down her mask. Heart pounding, the unranked Shang faces down a ranked opponent named Czarina Alfonso in a regional competition in New Jersey. The referee utters “en-garde.” Gripping her foil sword, Shang enters her stance and prepares for the bout. The referee issues a “pret” and then an “allez,” and Shang pounces on her opponent.

In first grade, Shang adopted fencing as a hobby per the suggestion of her family. Shang, at the age of six, found the equipment heavy and the agile sport grueling.

“I’ve been on and off, the super-heavy equipment is hard [to wear] as a child,” Shang said. “I ended up stopping for some years, focusing on other activities. I got back into it around middle school [in] seventh grade.”

Once Shang re-adopted fencing in middle school, there has been little to stop her from frequenting her fencing club and many local, regional and national tournaments. Shang trains for multiple hours a day and multiple days a week.

“Usually, training is three times a week for two hours [at a time],” Shang said. “Private lessons [are] twice a week for half an hour.”

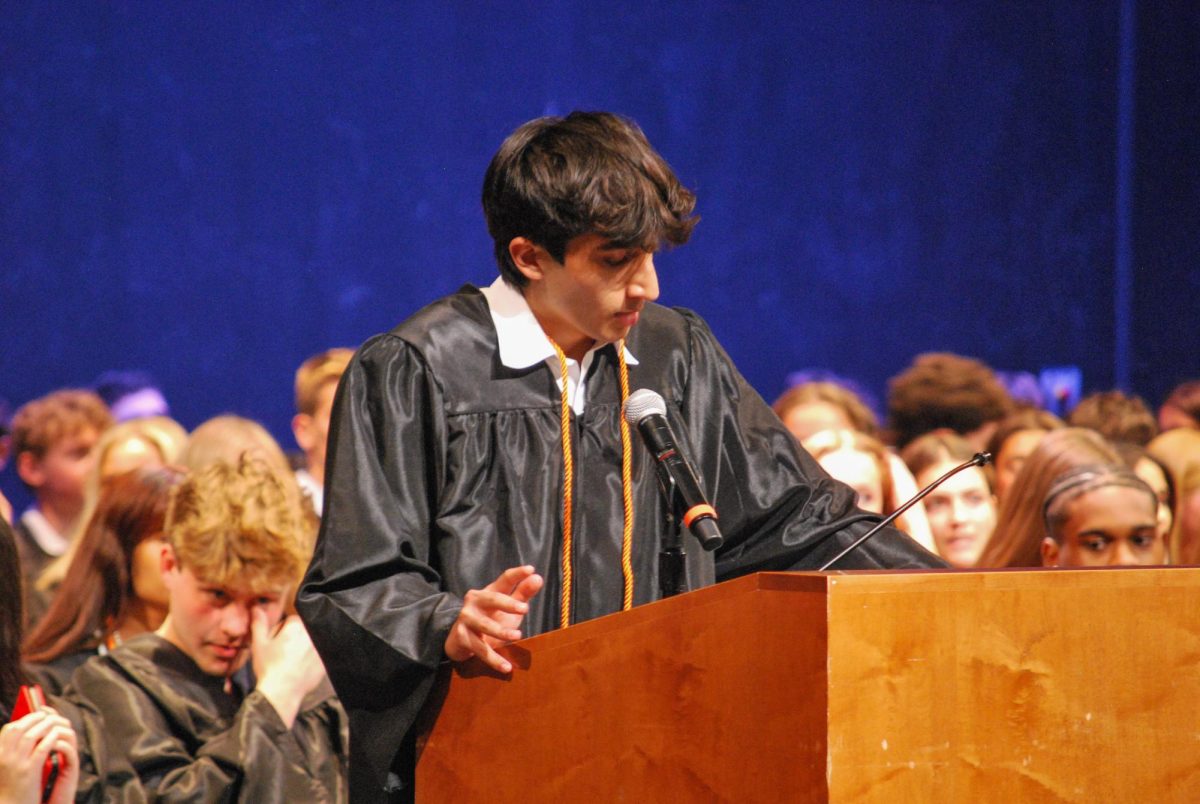

Shang competes in a foil bout at the 2018 North American Cup. The competition was held in Nov. 2018.

Shang trains at Gold Fencing Club in Waltham, Massachusetts. She has been under the guidance of multiple prominent fencers, including coach Huifeng Wang. Wang competed in the 1992 Barcelona Olympic games, where she earned a silver medal in women’s individual foil. Wang also has a plethora of gold and bronze medals for foil fencing in Chinese national competitions and the Asian Games.

The club boasts multiple rankings from National Fencing Club Rankings for foil events, including the title of one of the NFCR’s Best Fencing Clubs of the 2015-2016 season.

Being able to fence at such an illustrious club, Shang has competed in multiple competitions across the northeast and the country.

“Competitions range from local competitions in Boston to divisional competitions in New England, [even] New Jersey or New York,” Shang said. “And then [there are] national competitions [around] the U.S.”

Although Shang has not yet worked her way up to national prominence, she has appeared in national competitions such as the North American Cup and Summer Nationals.

“Every month, there’s a competition called a NAC, or North American Cup,” Shang said. “At the end of the fencing season in July, there’s a giant competition called Summer Nationals. It marks the end of the season, and it’s the biggest national competition. It’s a super big competition – there [are] like 200, 300 people per event. Even if you’re pretty good, it’s still a lot.”

Shang (left) converses with teammates at a team foil competition in Kansas City.

Shang has come a long way toward improving her fencing ability. The sport can often be frustrating for beginners, and victory may not come until years of practice are had.

“For the first one, two, maybe three years, you have to lose almost every bout you fence,” Shang said. “That’s really hard to get over mentally because you never want to lose. And, if you lose, you have to tell yourself, ‘I can get better.’ Then, after maybe two years, you can finally start to see a little bit of progress. The distance from beginner to a little bit before beginner is a long way to go.”

The basics of fencing are unlike that of many other sports. It’s a combination of agility, physicality and mental tenacity. Shang believes fencing is unlike any other sport in that the strategy of each bout can be extremely taxing.

“The thing that is different is that in fencing, it’s very thought oriented,” Shang said. “You have to hit one target, and it’s considerably smaller than [that of] other sports. You have to think about how your opponent will react to your reactions and then all the different possibilities they could [counter with].”

“When you do something, you have already planned two or three steps ahead,” Shang said. “It’s very detailed and [difficult] because it’s thinking oriented. It’s not just body – if you’re stronger [or] faster, it may not help you.”

Fencing, unlike most other sports, is based strictly on developmental skills. Like most other sports, however, it is the objective of every young athlete to find inspiration to model their own game after. For Shang, it is Olympic foil-fencer Lee Kiefer.

“Fencing is not a profession. Maybe in basketball [or] football, you get sponsorships – for fencing, you don’t,” Shang said. “All professional fencers tend to have a side job. Lee Kiefer just started medical school, and, at the same time, [she’s] preparing for the Olympics.”

Kiefer fenced her way to an individual NCAA Championship at Notre Dame. She’s an aspiring doctor, and she has taught Shang that it is possible to do both. Kiefer stands at 5’4 and overpowers competition with skill instead of physicality.

“People get the tendency to think you have to have really long arms or you have to be tall [to fence],” Shang said. “[Kiefer] just uses her speed, ability and practice. Even though she’s smaller, she [proves] anyone can have an opportunity as long as they work hard enough.”

Shang understands the dedication needed to be a good fencer. It is a level of commitment and perseverance which allows every fencer to be great.

“I was facing this girl, and I kind of had no hope because I knew she was really good,” Shang said. “I think because I considered myself very much a beginner at the time, I just did not expect anything out of it. I think as you fence, you just never know what’s going to happen. Maybe it’s a style issue for [your opponent], or they can’t adjust. I think the most memorable moment was when I thought I couldn’t do it, but [I] just kept pushing through, and I ended up beating her.”

Fencers are assigned ranks based on their performance in competition. Before beating Alfonso, Shang was unranked. Exiting her victorious bout, she rose to a “C” rank, skipping the lowest “E” tier. Shang is now aspiring to raise her rank and grow as a fencer.

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)