Andrew Yang: Eye of the Blue Hurricane

Credit: Nathan Zhao

Presidential candidate Andrew Yang speaks at a rally in Plaistow, New Hampshire. Yang has built a campaign off of a commitment to the issues, zeroing in on universal basic income and how best to adapt to automation. “I don’t feel like any of us on this campaign feel like figuring out who has the best solutions comes from attacking one another as candidates,” Yang’s deputy press secretary Hilary Kinney said.

“We’re up here with make-up on our faces and our rehearsed attack lines, playing roles in this reality TV show. It’s one reason why we elected a reality TV star as our president.”

Applause.

“We need to be laser focused on solving the real challenges of today.”

Wild applause.

10.7 million Americans tuned into the second night of the Detroit Democratic debates on July 31, and a considerable portion of that 10.7 million stayed for Andrew Yang’s closing statement, a bleak meta-analysis about a hidden defect within our democratic process.

Yang on center stage during the first day of Collision 2018 at Ernest N. Morial Convention Center in New Orleans, Louisiana.

More often than not, presidential candidates forego policy for politics, and who can blame them? The average American slumps down on their recliner, cold drink in hand to ease their senses after a brutal workday. The last thing they want to hear about is Amy Klobuchar’s plan for revitalizing American infrastructure needs. But how Obama’s own vice president was a secret racist? Turn the volume up.

Slinging insults to win an election is nothing new. Obama’s done it, Romney’s done it, McCain’s done it, Bush Old and Bush Young have done it, and so has every single candidate since the Neolithic Age when cavemen engaged in frenzied grunting battles for tribal dominance.

But not Andrew Yang. At this point, most probably know him as the “guy who wants to give everyone $1,000 a month” if not “the Asian guy running for president who stood next to Joe Biden on CNN that one time.”

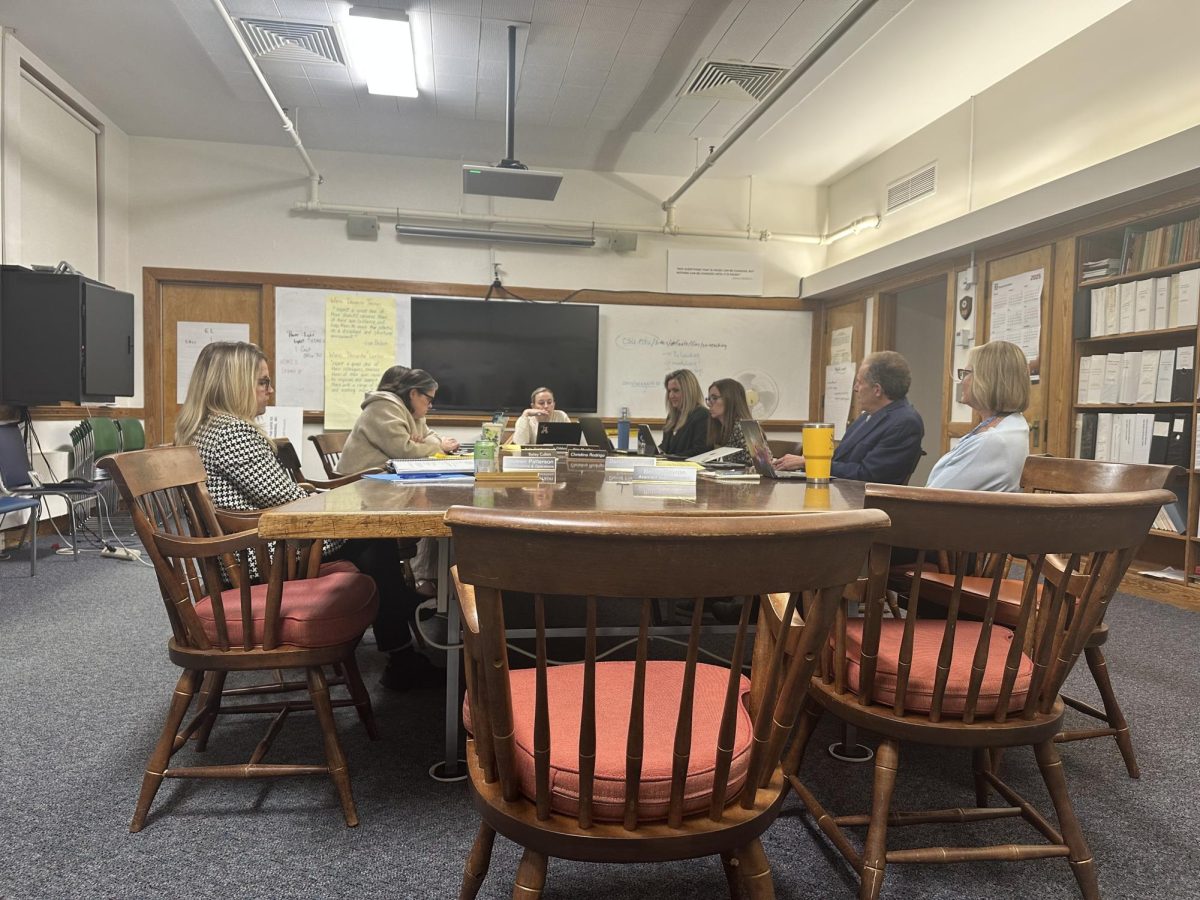

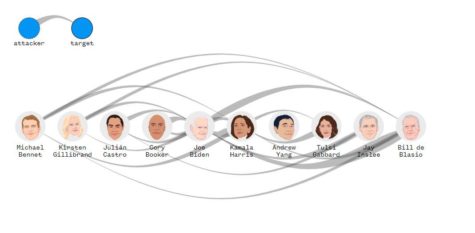

That said, the “Yang Gang,” as his supporters call themselves, is not inordinately passionate and loyal to its leader because of his race or even his policy, but because Yang rises above identity politics, expressing a rare, true desire to address the needs of the American people with genuine, thoughtful solutions. In that second round of debates in July, Yang was the sole candidate in both nights to neither attack nor get attacked by another Democrat.

This infographic illustrates how Yang was the sole candidate to never attack nor get attacked by a Democrat during the second round of debates in July.

At a rally in Plaistow, New Hampshire in late August, Yang extended his high-road stance to not only fellow Democrats, but to President Donald Trump as well. Where conventional candidates go after collusion, corruption and incompetence at any utterance of Trump’s name, Yang chooses a different route.

“Donald Trump identified the right problem, but he had the wrong solution,” Yang said. “When you go to a factory in Michigan, you don’t see immigrants taking all the jobs. You see automation.”

The “problem” Yang spoke of was the disappearance of manufacturing jobs that led to critical swing states such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania to vote for Trump and his promise that fighting off immigrants would reclaim the Rust Belt’s lost jobs.

Yang plays the “nerd angle” for his campaign, and one of his favorite statistics is that “Amazon is sucking up 30% of shopping malls like a giant vacuum and paying $0 in taxes.” Yang warns that cities such as Cleveland, Baltimore and Detroit are at risk of enduring deep economic scars from the “Fourth Industrial Revolution” of automation if the American government fails to properly adapt.

“If you make that flight [from Manhattan to Michigan], you feel like you’re traversing dimensions or decades or ways of life and not just a few time zones,” Yang said.

Whereas Yang traditionally avoids ragging on Trump’s character and instead goes after the president’s policy, one particular moment on the campaign trail questioned the consistency of this cause.

Yang with a turkey leg at the Iowa State Fair on Aug. 9. Near the end of the event, Yang ripped into Trump’s weight in front of a press gaggle. The campaign has since called it a “very isolated occurrence.”

At the Iowa State Fair in mid-August, Yang ripped into Trump’s weight for a good two-and-a-half minutes. But unlike the rally at Plaistow where a crowd of hundreds would roar at every one of his cheesy puns and quips, the press gaggle at the fair remained uncomfortably silent as Yang unsuccessfully attempted to land jibe after jibe.

“I don’t think Donald Trump could run a mile,” Yang said at the fair. “Would you guys enjoy trying to watch Donald Trump run a mile? That’d be hysterical. What does that guy weigh, like, 280 [pounds] or something?”

Yang’s campaign attempted to get him back on message, but he decided to push forward with the attack.

“I want to go through this intellectually,” Yang said. “Like, what could Donald Trump possibly be better than me at? An eating contest?”

Yang’s answer to his own question wasn’t much more intellectual.

“If there was a hot-air balloon that was rising and you needed to try and keep it on the ground, he would be better than me at that,” Yang said. “Because he is so fat.”

Yang’s attack missed the insult criteria that got Trump so far in 2016 and got Kamala Harris into fourth place following her assault on former Vice President Joe Biden during the first debate back in June. Yang failed to even tangentially connect the attack with policy, failed to read an obviously unentertained audience and failed to abide by the most important rule of comedy: never explain the joke.

A large portion of Yang’s following is Internet-based, and over sixty thousand have coalesced at /r/YangForPresidentHQ on Reddit, the self-proclaimed “front page of the Internet.” Following the incident at the state fair, a post denouncing Yang for his rhetoric accrued two thousand “upvotes” and 508 comments.

Hilary Kinney, Yang’s deputy press secretary, claims that Yang didn’t plan to go after Trump’s weight.

“It wasn’t really a strategy,” Kinney said. “I think it was just a part of Andrew speaking off the cuff.”

Kinney affirms that the attack on Trump was a “very, very isolated occurrence” and attributes it to Yang’s lack of experience.

“He’s never run for office,” Kinney said. “This is his first time interacting with the press at this high of a level. We are continuing to work with him to be able to field the best questions.”

Following the state fair, Yang avoided making similar comments on Trump’s weight, instead going back to centering his criticism around the president’s policies.

“I don’t think [he meant what he said],” Kinney said. “Andrew has always been someone to stay on the issues.”

The occurrence in Iowa, however, raises the question of whether or not Yang has enough experience to be prepared for the rigors of the presidency if he slips up at minor press gatherings.

“We all have different sorts of experience that we’re bringing to bear,” Yang said in an interview with The Intercept. “I would suggest that someone who’s spent years trying to create thousands of jobs and succeeding in the Midwest and the South is keenly aware of the challenges.”

Yang receives cheers and applause from potential voters in Plaistow, New Hampshire on Aug. 16.

Prior to the September debate, which attracted 14 million viewers, Kinney reiterated Yang’s commitment to policy, stating that the campaign did not prepare any of the “rehearsed attack lines” that Yang spoke ill of back in July.

“We [didn’t] have an attack plan,” Kinney said. “We really focused on what sets our ideas apart from the ideas of other candidates.”

The chief idea that has differentiated Yang’s campaign is his “Freedom Dividend,” a universal basic income plan funded by a value-added tax that guarantees every American $1,000 a month. Yang has taken flack for overemphasizing the Freedom Dividend in the debates, leading some to discard him as a one-trick-pony.

“We really want [Yang] to focus on other issues, too,” Kinney said. “Although a Freedom Dividend could solve a lot of problems, it won’t necessarily solve all of them.”

Yang, however, opened up the Sept. 12 debate with a blistering $120,000 taste test of the Freedom Dividend that incurred condescending laughter from some of his peers.

Yang at the Iowa State Fair in August. Among heavy-hitters such as Biden, Sanders and Warren, Yang connected with potential supporters. Iowa will caucus on Feb. 3, 2020.

The polls tell a different story: Yang’s message is working. A Sept. 18 Emerson survey finds that Yang moved up to fourth place in California with 7% polling, beating out home-state candidate Kamala Harris, who couldn’t keep her composure for a good ten seconds following Yang’s opening statement at the debate six days prior.

Yang also polls at 17% nationally among 18-29 year-olds according to an Aug. 27 Emerson poll. His campaign, however, still remains on the fringe of a three-way brawl between behemoths Biden, Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Sen. Bernie Sanders. In order to pick up steam before time runs out, Yang will need to stay on message not only in terms of policy but in his general strategy as well.

Identity politics doesn’t work for him, and it doesn’t need to. Where voters grow fatigued from nine candidates on the stage swinging blow after blow, they need to turn to Yang as the one who will bring the country together rather than tear it apart. In a hurricane careening left and right with the weight of an endless onslaught, Yang must stay in the eye of the storm, lest he succumb to the raging blue tempest around him.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Wayland High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, cover our annual website hosting costs and sponsor admission and traveling costs for the annual JEA journalism convention.

Kevin Wang, Class of 2020, is an editor-in-chief of WSPN, and this is his fourth year on the staff. He is captain of Wayland’s Speech & Debate team,...

Nathan Zhao, class of 2019, is a co-editor-in-chief of WSPN. This is his fourth year on staff. Previously to becoming EIC, Nathan served as the news section...