A small town with a big COVID-19 crisis: Welcome to Washington, Missouri

Credit: Elizabeth Zhong

Similarly to many states, Washington, Missouri battled its own struggles with the coronavirus. Junior guest writer Tully Jay spoke with Washington residents to better understand the complexities of the state’s mask mandate.

January 15, 2021

Here in Wayland, most people were quick to accept a mask mandate—especially at school where students and staff wear masks all day with the biggest complaint often being “my ears hurt.” Even at sports practices where masks can actually affect performance, athletes and coaches alike understand that it is a necessary inconvenience and deal with it.

It’s great that, here, residents are willing to wear masks, but in other parts of the country, some people are not as willing to wear masks.

Washington, Missouri, a small town of 14,000 and an hour west of St. Louis, tried to institute a mask mandate in Aug. The measure was rejected in a 4-4 vote by the town council with the mayor casting a tie-breaking nay vote. This was partly due to the perception of coronavirus as a “big city problem” and safety measures as infringements on their freedoms. A letter declaring opposition to being “forced to cover our mouths in public” received 356 signatures. Councilman Hidritch also stated that he has “ returned 350-400 emails… [and] 67% of those people tell [him] they don’t want a mask mandate.” Weddings and other social gatherings were common. All this was occurring as the local hospital urged COVID-19 restrictions.

As of Dec. 14, the U.S. has confirmed 19.1 million cases and over 333,000 deaths of the coronavirus. In nine of the past 11 days, there have been over 200,000 new cases. The past two weeks have seen an average of over 2,100 deaths per day, and hospitalizations increased 19% with over 100,000 hospitalizations on Sunday alone.

Such staggering and terrifying statistics should make simple yet extremely effective safety measures like wearing a mask commonplace and nonnegotiable. Yet, in 12 states, there is no mask mandate, and when the notion of one is suggested, protesters swarm the homes of local officials.

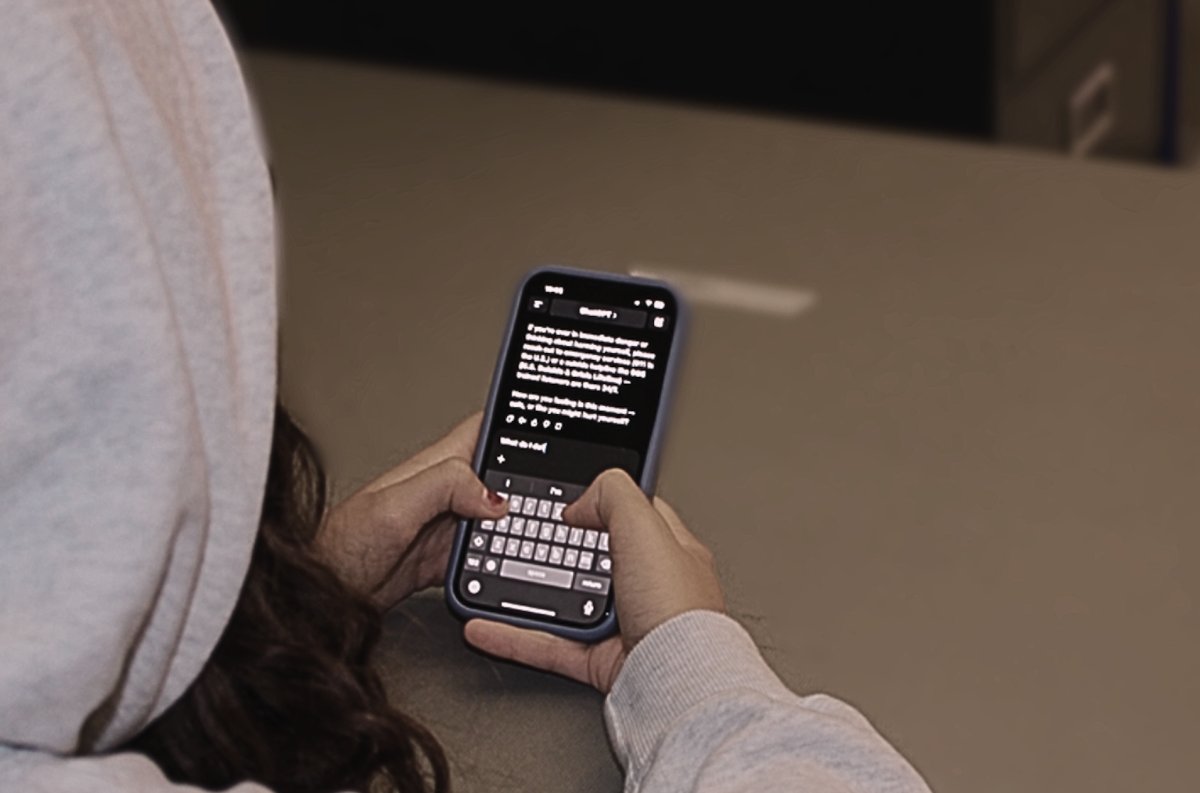

Kenneth Remy is an ICU doctor at Barnes Jewish hospital in St. Louis Missouri. On Nov. 20, Dr. Remy posted a video in which he pleaded for people to wear masks. “I hope the last moments of your life don’t look like this,” Remy said, holding a Macintosh Laryngoscope Blade and an 8 millimeter cuffed endotracheal tube over the camera, simulating the last thing COVID-19 patients see before being intubated.

Dr. Remy and his co-workers at the hospital noticed a similar exhaustion in each other—one that comes from months of treating a seemingly endless flow of patients, tireless work, and loss. Dr. Remy has treated over 1,000 COVID-19 patients and has intubated more than 100 of them.

When a patient dies of COVID-19, someone is responsible for calling family members to notify them. This job often falls to Dr. Remy. “It’s the worst way to start a conversation,” Remy said. “Your loved one’s heart has stopped. We did everything we could do.” In one week he had to make 12 of these calls — all but one was COVID related.

It was one of these calls that pushed Dr. Remy to film his plea for people to wear masks. At 6:30 a.m., after an overnight shift, and a call to a family, he had had enough.

Rishi Seth, a doctor in the special care unit in Fargo, North Dakota, reported a similar pain inflicted by the pandemic. Dr. Seth recalled a heartbreaking story in which a patient refused to be intubated after seeing three others placed on ventilators, two of whom were coded—that patient died.

“He became a friend… you get to really know these people,” Seth said, explaining a bond that develops with his patients. “On the two days before he passed away… [he told] his daughters ‘I think my time is up. I don’t think I can fight anymore’… he told his daughters how proud he was of them.”

In six weeks, Kansas has had a 64% increase in new cases per day. Director of infection prevention at Ascension Via Christi Hospitals in Wichita Dr. Hagan echoed the exhaustion felt by Dr. Remy and Dr. Seth, “[We] on the frontline have really seen the suffering and tragedy associated with [the pandemic].”

Her hospital had to create five new coronavirus wards to handle the surge of patients. To help treat the patients, Dr. Hagan has worked back-to-back 12-hour shifts for six weeks straight, seeing 50 patients every day.

Many of us often consider the pandemic by assessing how it affects us personally, leaving many blind to the tragic and deadly effects seen daily in hospitals. This is why some in Washington view COVID-19 as a ‘big city problem,’ and rejected a mask mandate in Aug. However, on Nov. 23, a second vote was held, and the mask mandate was passed 5-2 (with one absent). Councilman Obermark was the only one to flip his vote. What changed was how the pandemic affected him.

“It was several things that made me change my mind,” Obermark said. Mercy Hospital was running out of capacity, several healthy people he knew who were ‘knocked down’ by COVID-19 and his wife had to quarantine. And, on Oct. 31, Peyton Baumgarth, a 13-year-old eighth-grader at Washington Middle School, died from COVID-19. Peyton was the first person under 18 to die from the virus in the state.

“Overall I would say the reaction to the mandate has been positive,” Obermark said. “And people have been complying with the mandate.” Even in a neighboring town that does not have a mask mandate, Obermark observed that “quite a few people still were wearing their masks.”

Unlike other mask mandates, the one in Washington does not have an end date. “[Ours] is enforced by a metric system,” Obermark said. “It takes into account the number of positive tests and COVID-19 related deaths in the county and [the] number of available beds in our local hospital.” Until two of the three metrics stay out of the red zone for four consecutive weeks, the mandate will stay in effect. Currently, all three metrics are in the red zone.

Even still, some Washington residents protest the mask mandate. “Yes, there are still some protesters against the wearing of masks,” Obermark said. “I cannot speak for [them]. I have received [emails] including things such as infringement on personal freedom [and] medical conditions.”

This may be where the country runs into problems. As Obermark put it, “a lot of people have their minds made up—most will wear a mask if they have to. There are some that will not.”

Doctors across the country are working around the clock, seeing too many patients, organizing FaceTime calls for families to say goodbye and often have to notify families of the death of their loved one. They have been begging people to take these simple precautions, but some don’t listen even after it starts to affect their community. How many more people will have to be victims of this pandemic before it’s taken seriously?