Opinion: Dr. Seuss’ “cancellation” was long overdue

Warning: Contains racially insensitive Black caricatures

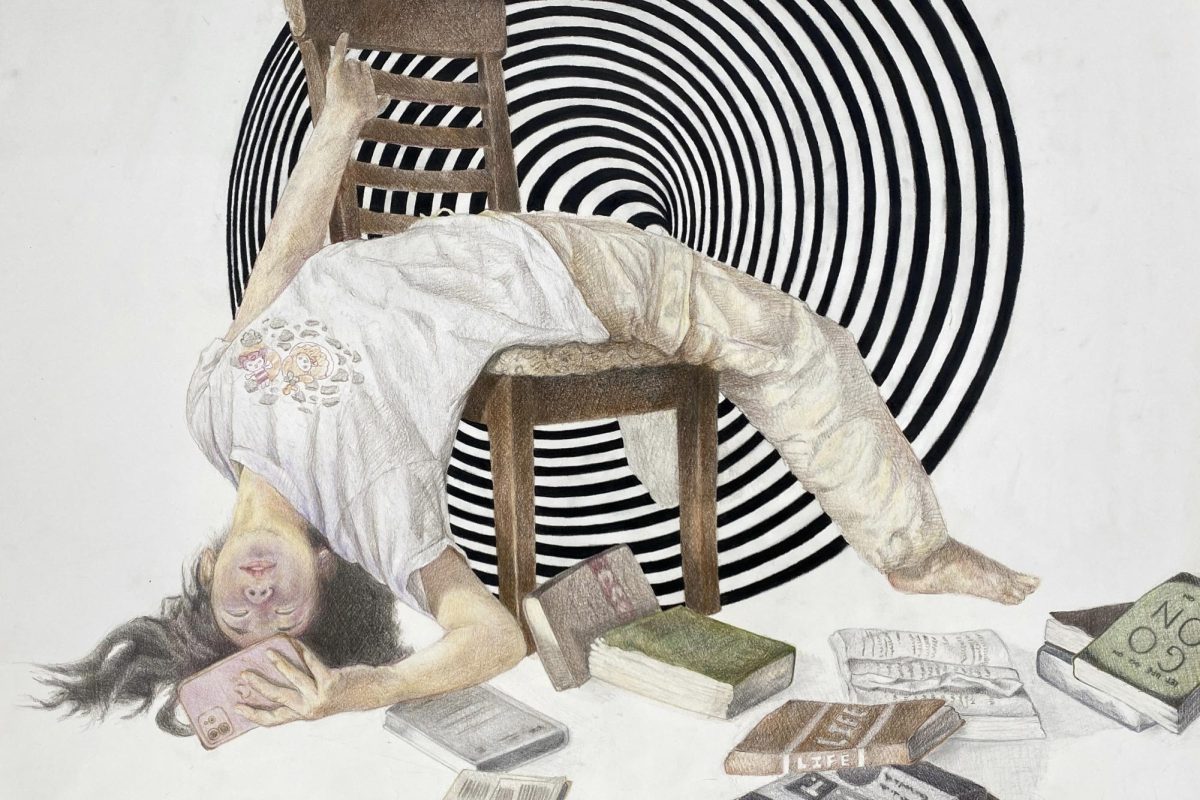

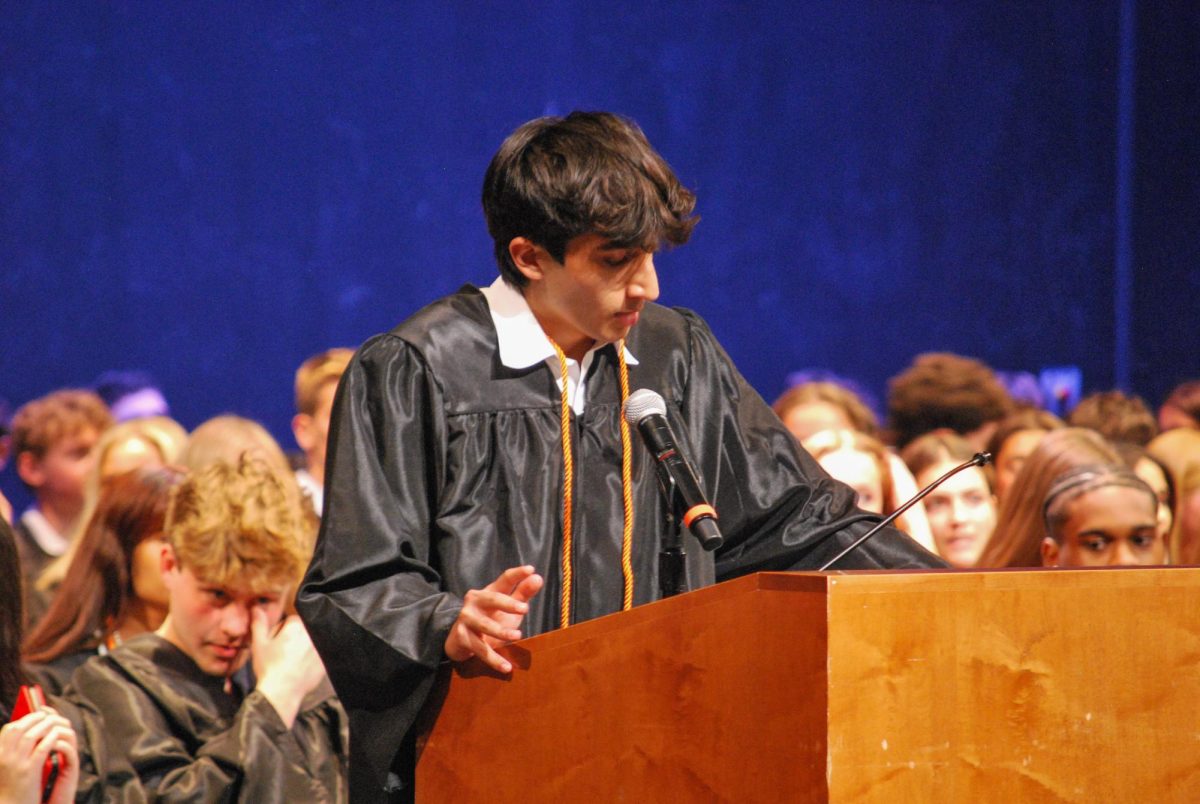

Credit: Atharva Weling

WSPN’s Atharva Weling discusses the accusations of “cancel culture” surrounding Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ decision to stop publishing copies of some Dr. Seuss books due to concerns about racial insensitivity.

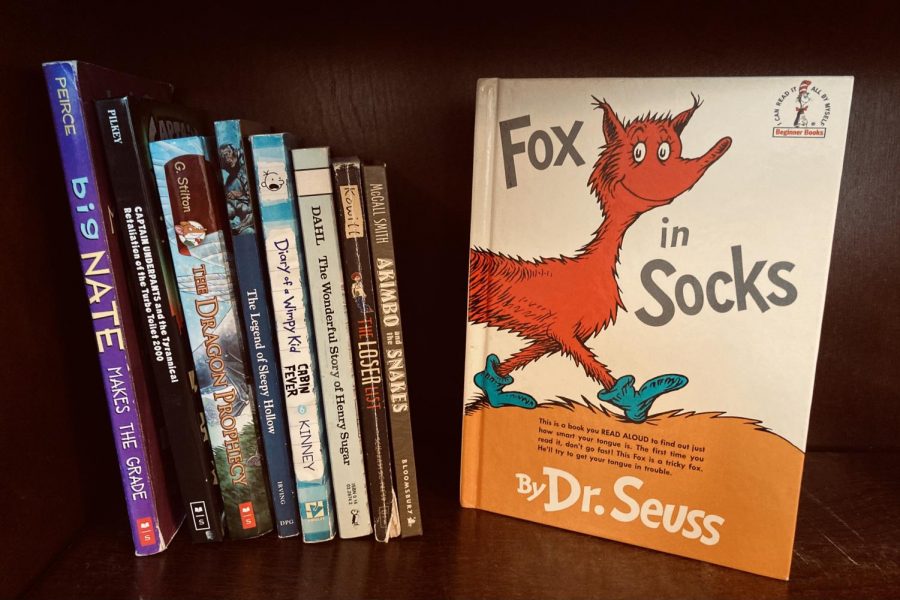

The assorted works of Theodor Geisel, more popularly known as Dr. Seuss, were an integral part of my elementary school experience. If I’m being honest, I never really cared for them, but they were everywhere when I was growing up. We ate green eggs and ham, sat on dirty gym mats in the cafeteria while the fifth graders acted out “The Lorax,” and at least once a year, listened to one of the teachers read a Dr. Seuss book aloud during library time.

One year, a teacher sat down in the old wooden rocking chair in front of our eagerly awaiting class, and read “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street.” Now, Dr. Seuss Enterprises has announced that they will no longer be publishing copies of that book, in addition to five other titles that the company deemed to “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.” That decision has sparked a firestorm of controversy, with some claiming that “cancel culture” in the wake of our nation’s reckoning with racial injustice has gone too far.

Media outlets on both sides of the political aisle have responded in an expected manner. Tucker Carlson decried criticisms of Dr. Seuss’s supposed racism as “demented” in his Fox News segment. On the other hand, Stephen Colbert praised Seuss Enterprises for listening to criticism and making “a change” during an episode of “The Late Show.” The only thing the two could seem to agree on was that many of Theodore Geisel’s most popular works, beloved by children nationwide, have become deeply sown into American culture.

However, a couple of years ago, long before both this Dr. Seuss controversy and the global protests for racial justice protests that triggered it, I was confronted with the same dilemma that many Seuss fans are facing today. A series of books, in fact a couple of series, that were far more influential in my developing years than Dr. Seuss ever was, were revealed to me to be racist. The experience that I had trying to reckon with that revelation shaped my understanding of racism in children’s literature in a dramatic fashion. It’s why I believe that “canceling” these Dr. Seuss books is a step in the right direction: both as a way to honor Theodore Geisel’s legacy and to protect today’s children from the racial intolerance he once preached.

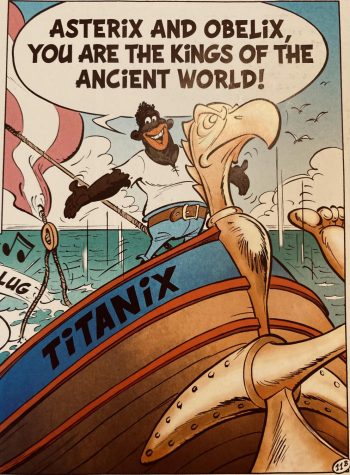

After completing his education and establishing a career, my grandfather moved to France in the 1960s to take a job for a few years. That experience, combined with the European culture he was exposed to while growing up under the British Raj, instilled in my grandfather a love of French comics: specifically, “Tintin” and “Asterix.” Almost as soon as I could read, he introduced them to me, and I loved them. My mind is filled with memories of going to the public library to read and reread their collections of both series. I perused stories about Tintin, the determined journalist, going to the Moon and Asterix, the brave Gaulish warrior, defeating hordes of Roman legionaries so many times that they are burned into my brain.

But as I grew up and started to learn more about the history of slavery and white supremacy, I couldn’t help but notice the overt racism present in these stories. On one of Tintin’s adventures, for instance, he finds a ship that is secretly transporting a group of African Muslims who have been told that they are going to Mecca, but are actually going to be sold into slavery. When I was a kid, those characters’ big red lips, bulging white eyes, and childlike personalities were nothing to me. They were just nonsensical, almost funny. But as a high school junior, having read “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and literature from Black authors about the harms of the minstrel caricature, the sinister truth became evident to me.

“Asterix” fared no better as I aged. Perhaps the worst part? That illustration of an African pirate captain wasn’t published in the 1960s when the comic first began. It was published in 2009, as part of its 50th-anniversary celebration edition.

The best parts of these stories, the daring adventures and the mysterious subplots, still meant something to me. I couldn’t just give them up. Nevertheless, I couldn’t stand some of the titles I had once relished reading anymore, so I just stopped reading them. The “Tintin” novel with the slave ship and the “Asterix” edition with the African pirate captain fell out of my rotation. The fantastic thing was that there were many, many books to choose from in both series that didn’t have those same racist overtones, and I could pick up any of them for a good old nostalgia trip.

We are fortunate enough to have a similar situation with Dr. Seuss’ works. Of the six books that have been canceled, none are true Seuss classics. None are the tale of “The Cat in the Hat,” or “The Lorax,” or even “One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish.” They comprise primarily of the doctor’s early work, and similarly to “Asterix” and “Tintin,” looking at the artwork that Theodore Geisel used for these books makes it difficult to ignore the caricatures present.

In the first book I mentioned, “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” we are greeted with images of “a Chinese man who eats with sticks.” In “If I Ran the Zoo,” we see “helpers who all wear their eyes at a slant” and characters from “the African island of Yerka” who bear an eerie resemblance to that same African pirate captain. They are the same caricatures I had to confront a couple of years ago when my cherished childhood books came under fire, and their presence in Dr. Seuss’s literature is unsurprising given the unabashed racism of his earlier cartoons both in and out of the field of children’s books.

Those depictions of Black and Asian people have real harms. In children outside of those ethnic groups, they can breed a sense of “otherness” towards minorities. They might not see real-life Black and Asian people as normal humans, like the white characters in those Seuss novels are portrayed, and that “otherness” can transform into hatred over time if left unchecked. For kids in those ethnic groups, it’s even worse. Speaking from personal experience, when you’re not represented in the media you consume as a kid, you develop a sense that you don’t belong in the society around you. Then, when the only representation you do get is either a stereotype or a caricature, you internalize those racist messages since they’re all you’re getting in the way of people who look like you. As a kid, how could you know any better?

However, those aren’t all of Dr. Seuss’ books of course. Geisel famously hated the Jim Crow policies of his time as well as the policies of Nazi Germany and the rampant antisemitism that plagued his society. All those values were reflected in his later works. In that Tucker Carlson segment I mentioned earlier, Carlson recounts the plot of “The Sneetches,” a Dr. Seuss classic that describes how two different looking groups of creatures, the star-bellied and plain-bellied Sneetches, learn to get along despite their different appearances. There are plenty of books, both bigoted and progressive, over the entirety of the Seuss collection.

Those who cry “cancel culture,” who think that their traditions are under attack, are trying to preserve a version of Dr. Seuss that only contains the good moments. “The Lorax” and “The Cat in the Hat” were their “Asterix” and “Tintin,” and they want to regard those novels and their creator as infallible. What we have to understand is that to regard anyone as infallible is just textbook denial. The bad side of Dr. Seuss was real, and it is our responsibility as a society to recognize it and make sure that it cannot spread its bad nature to the children of today.

If we want to honor the memory of Dr. Seuss, let’s do it by realizing that while he himself might not have always been racist, some of his actions certainly were. Let’s give our children the Lorax and the Cat in the Hat and the Sneetches that we once cherished, and the messages of love and unity that they spread. The books that Dr. Seuss Enterprises canceled were canceled because they couldn’t spread that same message, and if we want all of today’s kids to love these books as much as we did, it only makes sense to let them go.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Wayland High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, cover our annual website hosting costs and sponsor admission and traveling costs for the annual JEA journalism convention.

Atharva Weling, Class of 2021, is the opinions editor for WSPN in his second year on the staff. He runs cross-country and skis for Wayland and serves as...

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)