WHS administers health survey, seeks information about the well-being of students

Credit: Garrett Spooner

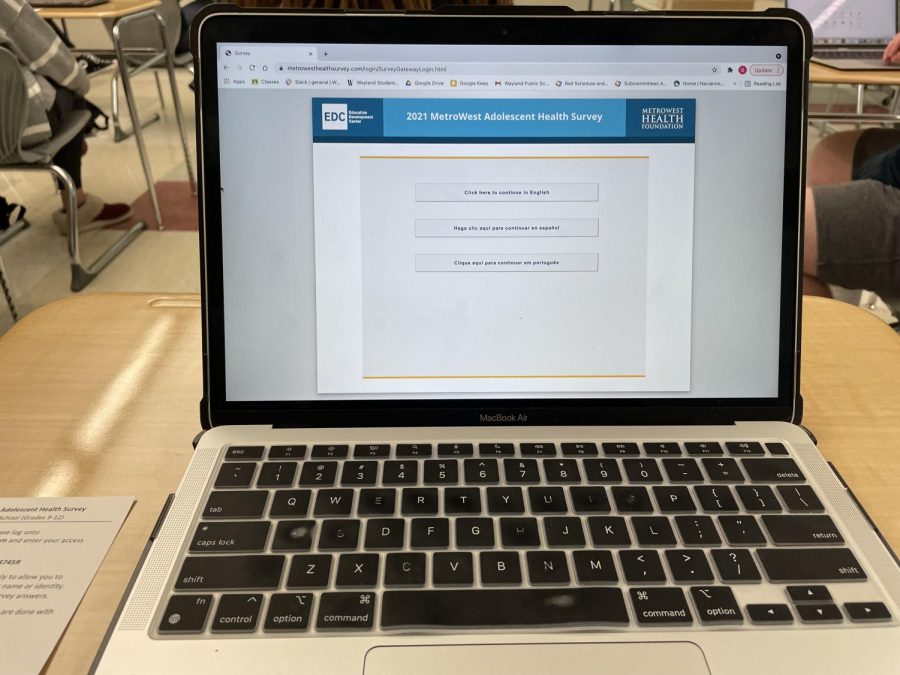

The opening to the MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey shows on a computer screen. On Tuesday, Nov. 9, all WHS students took the online survey during advisory block. “We’re excited that it was online this year, so we are hoping that we get the findings much earlier,” Mizoguchi said. “We tried to set a tone of ‘this is so helpful to us, please fill it out honestly’ so I’m hopeful that students felt safe enough to take it.”

November 16, 2021

With the goal of seeking methods to improve the overall health of students, Wayland High School administered the MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey on Tuesday, Nov. 9. Students took the survey during an extended advisory block.

The survey covered a wide range of topics: drugs, alcohol, mental health, school issues and more. However, WHS administration is more focused on some points over the others, especially in light of COVID-19.

“This year in particular we are focusing, especially as we come out of the pandemic, on the mental health of our students,” Principal Allyson Mizoguchi said. “We are looking at trends of anxiety and depression, and what has the isolation of the pandemic done to our students.”

Although Wayland was one of the first districts to participate in the survey, more districts have grown to administer it as well. Now, over 40,000 students in the state take part in the survey every other year. Because of that, Wayland has the opportunity to compare metrics internally and externally. However, Mizoguchi prefers looking at data within WHS.

“I take a special interest in seeing our own internal trends,” Mizoguchi said. “One point of data that we’re always interested in seeing is what percentage of students feel connected at the high school.”

Because of the data, WHS can implement new policies to improve the well-being of students.

“A lot of our educational curricula is a reflection of us pouring through the data and learning which concerns have become a trend,” Mizoguchi said. “With our wellness staffing, we’ve been able to defend a deeper wellness curriculum with the data that has come out of the survey.”

WHS administration gave students an hour-long advisory block to complete the survey, which consisted of over 100 questions. AP Statistics teacher Charlene Bishop believes that the survey itself was too long.

“I think the survey’s intentions are great, but they need to improve on the length,” Bishop said. “I talked to my students, and they tended to fizzle out after questions 40 and 50. They should break it up. The end of their survey is just not going to be reliable.”

Another bias that Bishop pointed out was who was administering the survey. Instead of teachers, Bishop believes that students should administer the survey to other students.

“You’re asking sensitive questions to kids and asking [teachers] to administer it,” Bishop said. “Ideally, they would get a more accurate result if they asked the student council to run the survey during lunch.”

After the survey was over, students had the rest of the period to do as they wished in their advisory. To some students, this choice inhibited the accuracy of the survey.

“I thought it was lengthy, and people seemed to tune out in class after getting through the first 50 questions,” an anonymous student said. “It didn’t seem entirely productive because people realized they could have free time to relax or play games on their computer once they finished.”

Although there were concerns, many students did believe that their peers completed the survey accurately.

“I think some people definitely did answer it honestly, [but] people were concerned whether the results would remain anonymous,” an anonymous student said.

Administration did what they could to ensure the survey would be filled out honestly, but ultimately, the decision was up to the students.

“We tried to set a tone of ‘this is so helpful to us, please fill it out honestly,’” Mizoguchi said. “I’m hopeful that students felt safe enough to take it.”