Attic Archeology: Local history makes history come alive in ways that kids can relate to

![History department head and Attic Archeology teacher Kevin Delaney uses a tool for students at a farm in Sherborn as part of a project on how life was like on a farm. Field studies are an important part of the course and students must be open to taking part in more unconventional forms of learning. “To be part of Attic Archeology, [you've] got to be willing to get dirt under your fingernails and be like ‘I don’t care, I’ll go muck around in the woods and see if we can find something,’” Delaney said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Screen-Shot-2020-11-09-at-9.45.55-AM.png)

Credit: Courtesy of Kevin Delaney

History department head and Attic Archeology teacher Kevin Delaney uses a tool for students at a farm in Sherborn as part of a project on how life was like on a farm. Field studies are an important part of the course and students must be open to taking part in more unconventional forms of learning. “To be part of Attic Archeology, [you’ve] got to be willing to get dirt under your fingernails and be like ‘I don’t care, I’ll go muck around in the woods and see if we can find something,’” Delaney said.

For seven years, the semester-long elective, Attic Archeology, has brought local social history to life for WHS students. Taught by history teacher and department head Kevin Delaney, the project and field studies-based class focuses on storytelling and discovering Wayland’s “hidden history.”

“I think local history makes history come alive in ways that kids can relate to,” Delaney said. “It’s not only the interesting area stories we uncover, but most importantly what the region can tell us about the big picture. Seeing how major national trends and developments played out in microcosm adds an enduring dimension to student understanding.”

The class was created for students looking for a high-interest and low-stress class. Because of this, Delaney thinks that Attic Archeology attracts students interested in taking a class for more than a grade.

“To be part of Attic Archeology, [you’ve] got to be willing to get dirt under your fingernails and be like ‘I don’t care, I’ll go muck around in the woods and see if we can find something,’” Delaney said. “You got to be willing to be part of the Island of Misfit Toys.”

Because Attic Archeology is optional and Delaney’s laid-back approach to teaching the course, Delaney has found that students find passion in their projects that they may not in other classes offered at WHS.

“You kind of catch a little fire,” Delaney said. “It piques an interest that I wish we could do more readily in a lot of our courses.”

The elective assigns minimal homework and is based around project work and field studies, so it allows more freedom for students and Delaney to learn and work without being constrained to a curriculum that could be time limiting.

“In [Attic Archeology], without the pressure of ‘hey, you’ve got to cover all of this information for U.S. history,’ you’re free to take as much time as you want,” Delaney said. “If you find something really interesting and you want to spend a few more days on it, then go for it. It’s kind of liberating in that way as a teacher.”

Delaney’s passion for history stems from when he was a child and grew up working at a cemetery and hoped to become an archeologist.

“I’ve always been interested in material remains,” Delaney said. “[I would go] digging around as a kid [in] old bottle dumps in the woods… It’s just how my brain works. I’ve always been interested in the unusual, funky stuff, the quirky things that people do and the remains we leave behind… [and] in the offbeat history.”

Working at the cemetery is what ignited Delaney’s curiosity about gravestones and when he discovered that they could tell stories. Now, the class runs a mortality project, requiring students to learn about gravestone carvings at Wayland’s Old North Cemetery in hopes of gaining insight into life in early Wayland. Students learn to read the carvings, “British America’s first folk art” as Delaney described it, which can be revealing about the person buried in the grave, such as their religion.

“All those people are buried six feet below,” Delaney said. “And how much they knew, and how many people they loved… what happened to all that? What happened to their memories? What happened to the stories and the love? It’s gone. But it was all so real and true and just like our lives. So, I thought, wouldn’t it be great to try to retrieve some of that and see if we can breathe some life back into these people who probably haven’t had a visitor in a generation or two.”

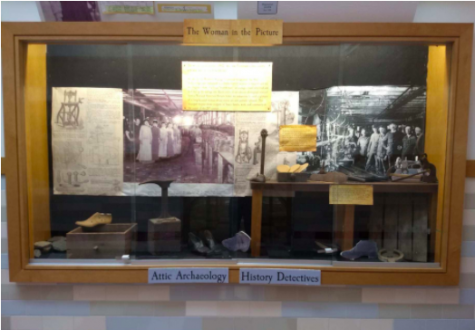

Attic Archeology is scheduled to be in the afternoon to accommodate field studies, which occur every two weeks during lunch or last block. Previous field studies include traveling to Yankee Craftsman, Mill Pond and the First Parish in Wayland, which was used as a “biography of a building” and taught students how to read historic structures. A trip to the Wayside Inn was used to study how the mill works. Students then created a model of the Cakebread Mill, which existed where Mill Pond is today, that had water, a working pump and a timeline that showed the pond’s uses throughout time, and was presented in the display case in the history wing.

“A clue might lead to something really interesting and that’s what’s exciting in the treasure hunt approach,” Delaney said.

This semester, Attic Archeology students will visit the Old North Cemetery and car wrecks in the Greenways Conservation Land, which Delaney hopes to use as a way to teach and learn about American suburban life.

“You’ve got the old cars in the woods and if these cars could talk, what stories would they tell?” Delaney said. “Whatever happened in families, the good, bad and everything in between, happened in those cars… We can put the stethoscope up to [those cars] and just try to imagine what happened in them.”

He believes that learning about local history that could be called ‘mundane’ or ‘ordinary’ is just as important as the events students are taught about in textbooks and history class.

“History is mostly boring, everyday life,” Delaney said. “Super exciting things that end up in history books happen .001 percent of the time. So what happens the other times?”

Although most projects have been done only once, some have been repeated over the years. At the beginning of every semester, students in Attic Archeology walk to the end of the WHS driveway and study the milestone, which measures 19 miles to Boston and was built in the 1760s.

Students are taught how to use artifacts like the milestone and other sources—Ancestry.com, yearbooks, digitized old Wayland Town Criers—to connect history and, as Delaney put it, “build it all together like a jigsaw puzzle.”

“We emphasize [skills when we] teach students how to use evidence—often unconventional in form—to piece together understanding in the form of stories,” Delaney said. “It’s actually a civic skill, similar to what jurors do when hearing a case: weighing evidence for reliability and then assigning appropriate weight in order to construct the most probable sequence of events.”

Students also write ghost stories. First, they study famous storytellers and learn how to write aspects of horror stories, like suspense. Then they use the “Wayland A to Z: A Dictionary of Then and Now” book to create an authentic historic Wayland setting and make podcasts of their original stories.

At the end of the semester, students’ projects made throughout the class aren’t published anywhere, going into a “hibernation.”

“What we do in Attic Archeology is more about the joy of the hunt and then what we discover as opposed to being sure that the legacy of what we discovered continues to be known for the next 10 years or 20 years,” Delaney said. “That’s not quite as important for me and the learning objectives for the class.”

Though the fate of Attic Archeology is uncertain as this is Delaney’s last year at WHS, he encourages those unable to take the class to explore ruins and abandoned properties, to speak with elder members of our community and to learn about one’s personal genealogy.

“There’s a lot of stuff around that is just kind of quirky and interesting in of themselves,” Delaney said. “So it’s worthwhile just because they’re neat little stories, but they also show you something bigger about attitudes that were prevalent in the area or in the country.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Wayland High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, cover our annual website hosting costs and sponsor admission and traveling costs for the annual JEA journalism convention.

Emily Chafe, Class of 2022, is a features editor for WSPN and is a third year reporter. In her free time, she enjoys photography, spending time outdoors,...

Julia Callini, Class of 2020, is a multimedia section editor for WSPN, and this is her third year on the staff. She is an optimist, feminist and a diehard...

Roberta Delaney • Dec 11, 2020 at 3:08 PM

Good for you, Emily. I’m Mr. Delaney’s mom….Attic Archaeology fact here…everyone has a mom. You did a terrific job . Best wishes to you and all your important classmate in the future. We, in the past, really need you.