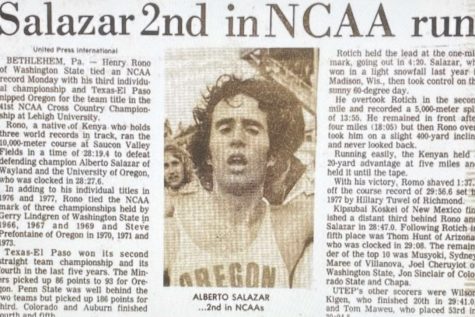

Alberto Salazar: From distinguished to disgraced

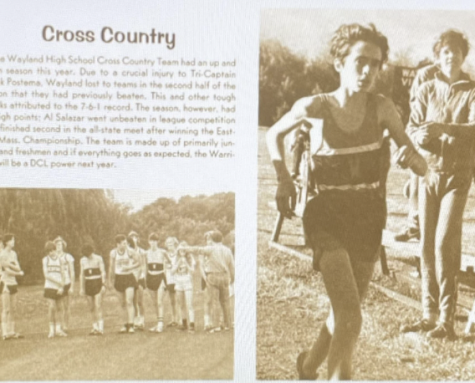

Credit: Courtesy of Wayland Yearbook

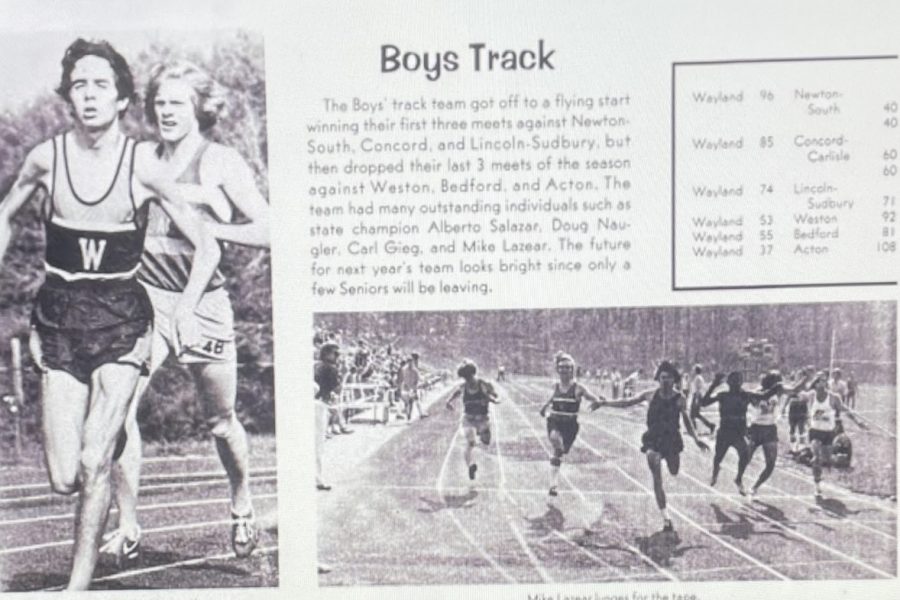

Wayland alumni Alberto Salazar runs for Wayland High School. Salazar was inducted into the WHS Hall of Fame in 2006 and since that has been barred from track and field but still remains in the Hall of Fame.

February 8, 2023

Alberto Salazar, a Wayland High School track star, WHS Hall of Fame (HOF) member and 1976 graduate, always seemed to be a lap ahead in his high school, professional and early coaching career before doping and sexual assault allegations left him barred from the very sport that made him famous.

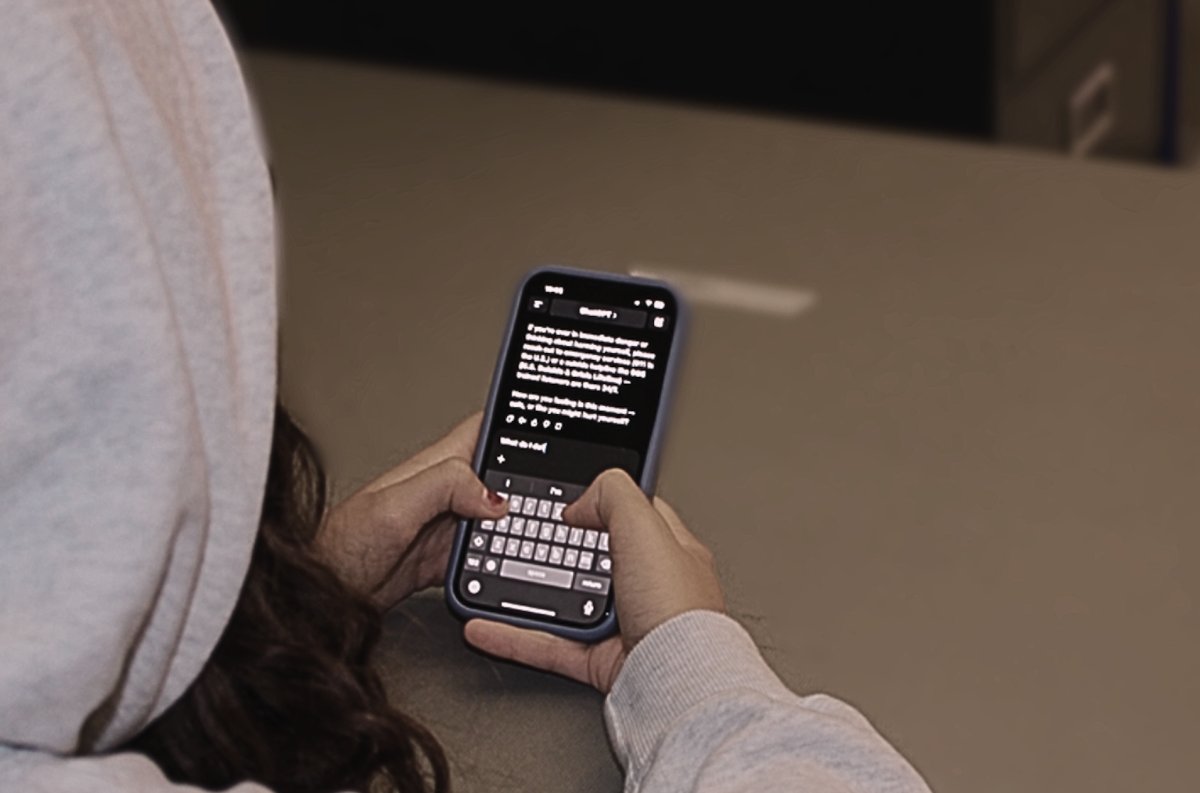

Today, Salazar’s name remains in the Hall of Fame in the WHS field house. The decision to keep his name up on the wall has the potential to be a controversial subject. However, many Wayland students and residents are unaware of this issue.

Salazar is among Massachusetts’s best runners and is the best runner Wayland High School has ever seen. To this day, he holds the Wayland indoor record in the 1,000 (2:19), mile (4:19.2) and two-mile (8:53.8). In addition, Salazar won the state cross country championship as a senior. He continued his running career at the University of Oregon and went on to win three New York Marathons (1980, ’81 and ’82) and the Boston Marathon in 1982.

For two decades, Salazar served as a coach for the Nike Corporation and as the highest-level coach of the Nike Oregon Project, which trained the best long-distance runners in the world from 2001-2019.

In 2004, Salazar was inducted into the Massachusetts Track Coaches Association Track Hall of Fame, and in 2006 he was inducted into the Wayland Hall of Fame. The Wayland Boosters created the Wayland Athletic Hall of Fame to honor coaches and alumni that left their mark on the Wayland High School Athletic Community. Since 2006, 63 past WHS players and coaches have been inducted into the Hall of Fame.

In 2019, Salazar’s career collapsed when he was suspended from track and field for four years due to doping violations. Since then, Salazar has been barred from the sport for life after being accused of sexual assault on two different occasions and bullying female athletes. Although Salazar has not been tried, he asked for an arbitration hearing, where the arbitrator found him likely to be guilty based on his lack of credibility compared to his accuser.

Even though he has not been criminally charged, the WHS Athletic Department removed the memorabilia dedicated to Salazar, formerly displayed in a case outside the field house. However, Salazar remains in both the Massachusetts and Wayland Halls of Fame, one of which stands in the Wayland Field House for all students to see.

“There is history that we could not erase with the Hall of Fame, so [Salazar’s name] is still up [on the wall],” WHS Athletic Director Heath Rollins said. “There’s online things, like the WHS track Hall of Fame, so even if we decided to remove [his name], that’s still gonna be out there in the public.”

While some people in the Wayland community are unaware of Salazar’s sexual assault and bullying accusations and even his existence in WHS history, the high school administration chose to act quickly when they became aware of the accusations against him. According to Rollins, when accusations towards Salazar initially arose, administration decided they wanted to tackle the problem head-on.

“It was a quick discussion back then with our administrators, kinda like, ‘Hey, we have this. What should we do?'” Rollins said. “I think at the time we said, ‘Oh, his name’s up in the Hall of Fame, and we don’t want to ignore the history, but we don’t want to celebrate what he ended up becoming.’ So we didn’t remove his name from the Hall of Fame, and it was really just a quick discussion.”

Although Rollins describes the interaction between administration as a clear consensus to keep Salazar’s name up on the Hall of Fame, Principal Allyson Mizoguchi remembers the conversation differently.

“I remember the issue coming up and talking briefly with Mr. Rollins about it, but I thought [the decision had] been to take the [Hall of Fame] plaque down,” Mizoguchi said.

Despite different accounts of past conversations between school officials, Salazar’s name is still displayed in the WHS Field House.

“I don’t know how much [of Salazar’s allegations] was on the public radar,” Rollins said. “It was on [the school officials’] because we know it’s there, but I don’t know how much it was in the know. Obviously, there were people who remembered who he was and brought up how disappointed they were in his actions.”

The Athletic Department hasn’t received any public inquiry, but it did receive an email from one of Salazar’s past coaches, Bill Snow, who was the Track and Field coach from 1971 to 2008. Snow declined to comment for this article.

“We did get an email from our cross country coach when [Salazar] was found [likely to be] guilty and was banned in 2019, saying that ‘you can’t erase what he did in the 80s as a marathoner and what he did in high school, but celebrating his success in the marathons after [high school] kinda becomes suspect’,” Assistant Athletic Director Erin Ryan said. “[The old cross country coach] felt that those types of things, the New York Marathon and the Boston Marathon, should come down and the high school stuff should stay.”

Although the HOF contains public records of WHS athletic achievements, the HOF’s decisions are inaccessible to residents and students, with the majority of the committee members declining to comment on this issue.

Decisions regarding the HOF aren’t entirely up to administrators. The HOF committee assists in making the executive decisions surrounding inductees, but the committee has seemingly unraveled in recent years. The last induction was in 2017 and inductions are supposed to take place every two years.

According to the HOF Website the board consists of Chris Brown, Heath Rollins (AD), Chris Jenny, Asa Foster, Eric Moyer and Bill Snow. In email and phone correspondences with Snow, Foster and Jenny, they said they are not current members of the board. Other members WSPN reached out to didn’t respond, or WSPN was unable to obtain their contact information.

According to Rollins, in 2017 the original HOF committee disbanded and turned leadership over to three individuals, who have not taken an active role in running the committee since then. Rollins said that he recently reached out to other individuals with hopes to resume inductions.

The committee inducts athletes through applications on the website and an evaluation process. Currently, Rollins has three applications for the Hall of Fame but a lack of committee leadership has prevented the committee from collaborating and adding anyone to the wall.

Despite the confusion surrounding the Wayland Hall of Fame selection process and the existence of the committee as a whole, Mizoguchi believes that Salazar does not reflect the ideals and beliefs of WHS.

“I can understand there being some ambiguity about what to do with this when things are undecided, but I think decisions have already been made about what he is and isn’t guilty of,” Mizoguchi said. “When we look around our school, we want to see representations of what we value. That’s why we have a peace flag, a Black Lives Matter flag and all these visual things are really important and reflect what we believe. I think we should seriously question celebrations or visual representations of individuals and ideas that are not in alignment with what we value here.”

To this day, Alberto Salazar holds the Wayland record for the one mile with a time of 4:19.2. Since 2002, the two people that have times closest to Salazar’s have been Brett Baker (4:28.74) and Lucas Thompson (4:32.5).

![This year, the Wayland team is made out of a JV team and a varsity team. There is a wide range of grades from eighth grade to twelfth grade that make up the teams. " [What] I will miss most [about the seniors] is their willingness to be involved," sophomore Mackenzie Grogan said. "Whether it was with school drama or referee frustration, they were really good at listening and giving good advice."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/8F0FD331-F005-4C3F-9F77-402D1C1953D6_1_201_a-1200x800.jpg)

Mark Mayall • Mar 29, 2023 at 9:41 AM

I’m the current WHS Cross Country coach, I very much appreciate this article and the important issues it raises. I’d like to add a bit of context, based on my own knowledge of the sport (competing athlete for almos 40 years, coaching cross country and track at various schools including Wayland since 1993):

In terms of athletic achievement alone, Salazar is almost certainly the most accomplished WHS athlete ever. If not he’s in the top two or three. He competed at a national level while in high school at Wayland. Subsequently he went on to compete at an international level in college (he’s in the University of Oregon Athletic Hall of Fame) and after college. He represented the USA in multiple international competitions including the 1984 Olympics. Comparing a distance runner to a basketball player, or tennis player, or rower, or softball player is like comparing apples and oranges but clearly his accomplishments while at WHS and beyond are at an elite level.

The more recent accusations regarding doping by athletes under his supervision and abusive treatment of athletes he was coaching sent shock waves through the world of competitive distance running when the details came to light. I can’t overstate this. Before his downfall he was considered by many to be the best coach of elite distance runners. He coached Mo Farah of Great Britain and Galen Rupp of the USA, who both medaled (Farah the gold) in the 2012 Olympics. There were multiple Olympians among his stable of athletes. He was also a divisive figure with rumors swirling around him about possible links to doping. While there is far less attention paid to “Athletics” (cross country, track and field and marathons) here in the USA compared to other parts of the world, the scandal around Salazar has been both national and international news. An internet search of his name yields articles from the New York Times, CNN, Sports Illustrated, and the Wall Street Journal. In 2015 Pro Publica published the definitive expose of the questions around doping allegations.

In 2019 one of Salazar’s former athletes, Mary Cain, wrote a scathing Op-ed piece in the New York Times detailing her allegations of his abusive treatment of her. The piece (I can’t link to it here) concludes with multiple athletes corroborating her claims and sharing their experiences as well. The piece has garnered almost 1300 reader comments. In 2021 Cain filed a $20 million lawsuit against Salazar.

Kara Goucher, another former athlete, has made similar accusations in recently published book.

When Mr. Rollins, for whom I have the greatest respect, says that he’s not sure how much of the allegations were on the public radar I think he’s likely referring to here in Wayland on a local level. I found when the scandal came to light in 2019 the athletes I was coaching at the time barely knew who Salazar was if they knew at all. Not surprising given how long ago he attended WHS, that his life after high school took him to the west coast, and that his accomplishments came in a sport that doesn’t get ten percent the attention of the four major professional sports. One athlete of mine at the time did come across a news story and asked me about it though, recognizing the Wayland connection. This is what motivated me to ask Mr. Rollins if anything should be done about the Salazar memorabilia in the display case at the entrance to the field house (as you mention it has since removed).

I’ve known Bill Snow since I was coaching track at Acton-Boxborough in the ’90s when he was coaching track at Wayland and I have the utmost respect for him. When he makes the distinction between recognizing/acknowledging what Salazar achieved as a WHS student versus celebrating what he did after leaving Wayland, it’s an important distinction. Ms. Mizoguchi’s questioning of celebrating individuals whose ideas and actions don’t align with WHS values is also well taken.

Should Salazar remain in the WHS Hall of Fame? I’m torn. His high school achievements came decades before the alleged conduct that led to his being banned from the sport in which he specializes. The Hall of Fame would seem to lose credibility without the person who in my opinion is the most accomplished athlete the school has ever produced. At the same time the magnitude of the accusations leveled against him make any celebration of him, even the teenage version from almost fifty years ago, not feel quite right. At the very least it seems there should be a disclaimer perhaps.

Mr. Galalis • Feb 8, 2023 at 11:42 AM

Great coverage of an important issue–Thank you!

One small tidbit about the fastest WHS mile times since 2002 from a former coach… 🙂 Brett Baker (Class of 2011) in fact ran a 4:28.05 at the Indoor DCL Championships in 2011. A rare instance of an indoor mile personal record (8 laps on a 200-meter track, as opposed to 4 on a 400-meter outdoor track) that was FASTER than his outdoor mile personal record (the 4:28.74, which he ran at the 2011 Weston Twilight meet).

Love the animated graphic!