“We should do everything we can to implement change:” Proposing a mandatory race class at WHS

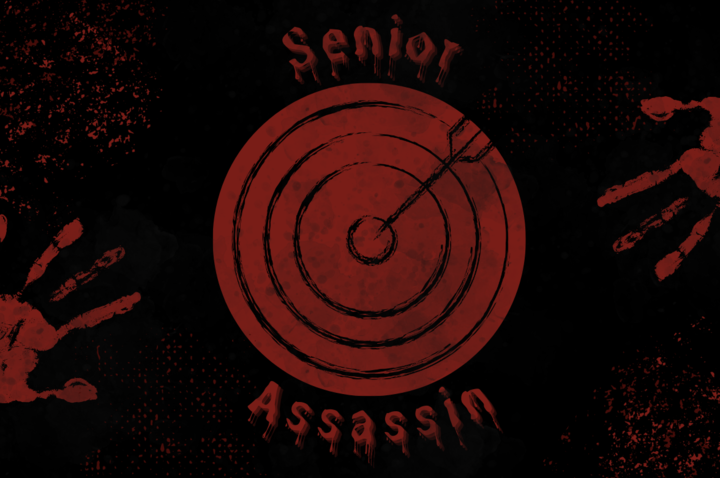

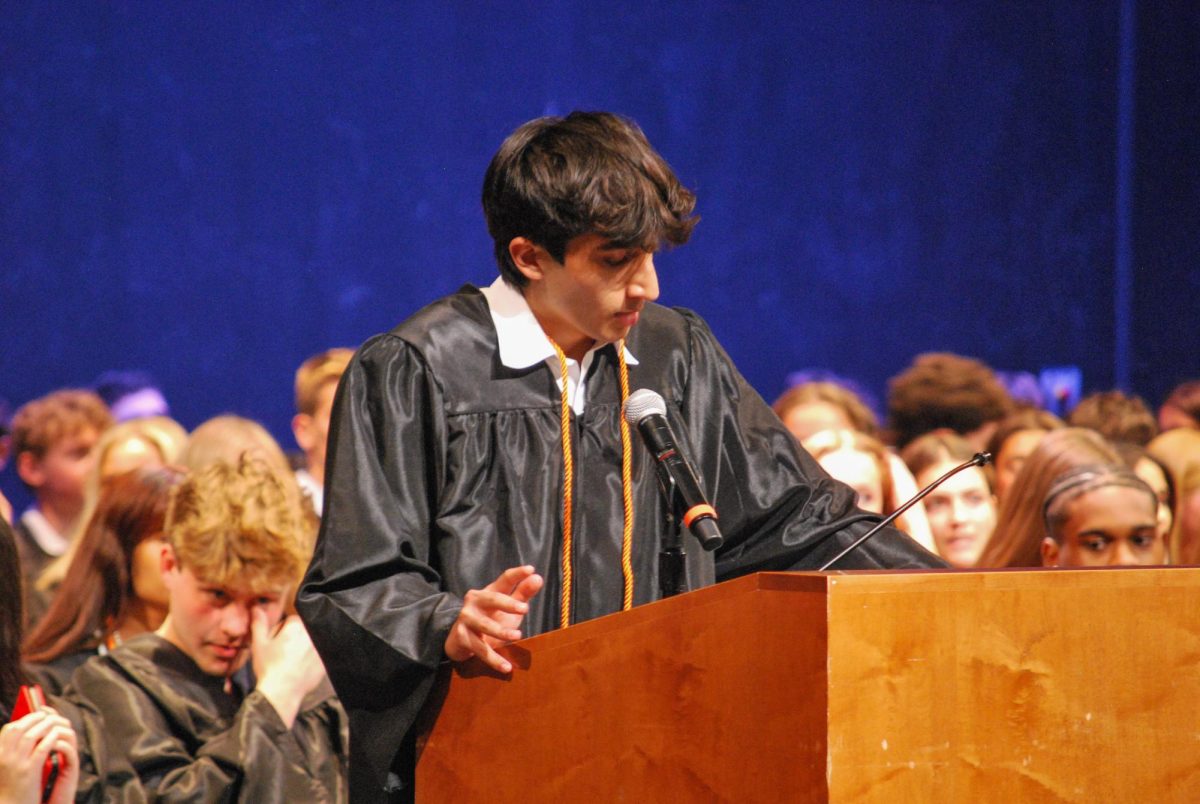

WHS alumni Lizzy Francis and Sam Goldstone began the process of creating a stand alone race class for freshmen in 2020. “I think that a large issue with this country in general, honestly, is just [people] being uneducated and being unaware of different experiences,” WHS alum Lizzy Francis said. “I think that [by] bringing awareness to these social situations, we become better people, and we create a new generation of people that are kinder to each other, willing to listen and willing to be advocates for those who can’t be advocates.”

June 17, 2022

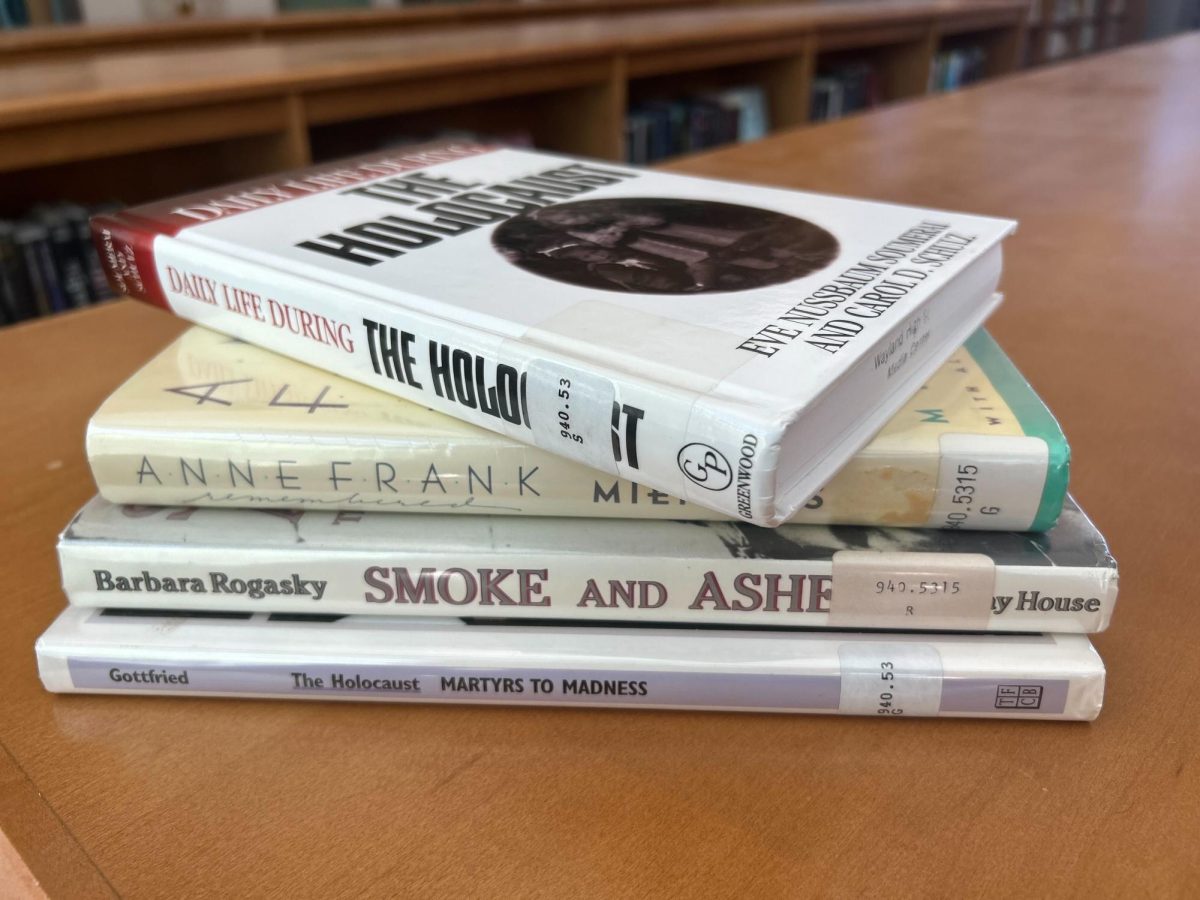

In the summer of 2020, as efforts to address contemporary racism gained attention across the country, that momentum also became widespread in classrooms in a nationwide push to diversify school curricula. WHS alum Lizzy Francis and then-senior Sam Goldstone decided to bring that initiative to Wayland in the form of a mandatory class that would educate students on the history of systemic racism and its lasting impacts.

Francis and Goldstone’s idea was to replace Infotech, a mandatory media literacy class for freshmen, with a class that would help provide incoming freshmen with a better fundamental understanding of race and racism, along with how students can best effectuate change in Wayland regarding race.

“In classes when we were learning about things, even though they were taught from this sort of egalitarian and demographically equal perspective, we didn’t really get the true perspective of what it meant to be a person of color during historical times,” Goldstone said. “We never really understood the source of systemic racism and how to combat it, as well as how it permeates our society today, and I think that that’s a facet of education that I so wish I had received in school.”

When Francis and Goldstone were originally discussing their proposal with teachers, they didn’t have concrete plans. The class would be what Francis described as “a safe space to ask uncomfortable questions about uncomfortable things.” The intention was to allow students of color to talk about their experiences, and for white students to be educated on subjects such as internalized biases and unconscious microaggressions.

“I think that in order to talk about race and to tackle racism and microaggressions, we need to hear from people who have first-handedly experienced [racism] and who experience it everyday,” Francis said.

The concept of the class is based on Francis and Goldstone’s belief that schools have an obligation to dedicate time to teach students how to become contributing citizens beyond traditional academic subjects.

“A lot of people don’t agree with me and think that school should simply be for learning math and science and English, but I think school should be for learning how to think and learning how to effectively create positive change in the world,” Goldstone said. “We all have implicit biases and not knowing that while going through life is a disservice to people.”

In 2021, Goldstone worked with history teacher Eva Urban to develop a curriculum for a unit on race within a citizenship elective, finding sources that would help to serve as a backbone for a new class. Francis and Goldstone previously met with administration to discuss their project, but had not formed a set curriculum.

“We don’t want to bring [a curriculum] up to administration and be like, ‘Here’s this little gift that we’re giving you, this is what we want for the class,’” Francis said. “We wanted more teachers to be participants in it. We wanted administration to be part of it. It should not be the job of two former students to create something so important.”

Earlier in the school year, multiple racist incidents occurred at Wayland Middle School, including racist graffiti found in a bathroom stall. Goldstone believes that starting as early as sixth grade, a class or a Wellness unit dedicated to race, racism and culture could help to prevent these incidents, as well as make students more mindful of the identities of their peers.

“The level of how unacceptable that is, I don’t think was conveyed in those students’ individual lives,” Goldstone said. “Looking back at my middle school experience, I definitely was in the room where people were being really offensive. The line [between] jokes versus ‘this is literally so racist,’ that line was never really drawn until later in my life. I think there are ways to help [draw] that line in everyone’s life, in a class, that would be very helpful to the development of many middle-schoolers, as well as high schoolers and people of all ages.”

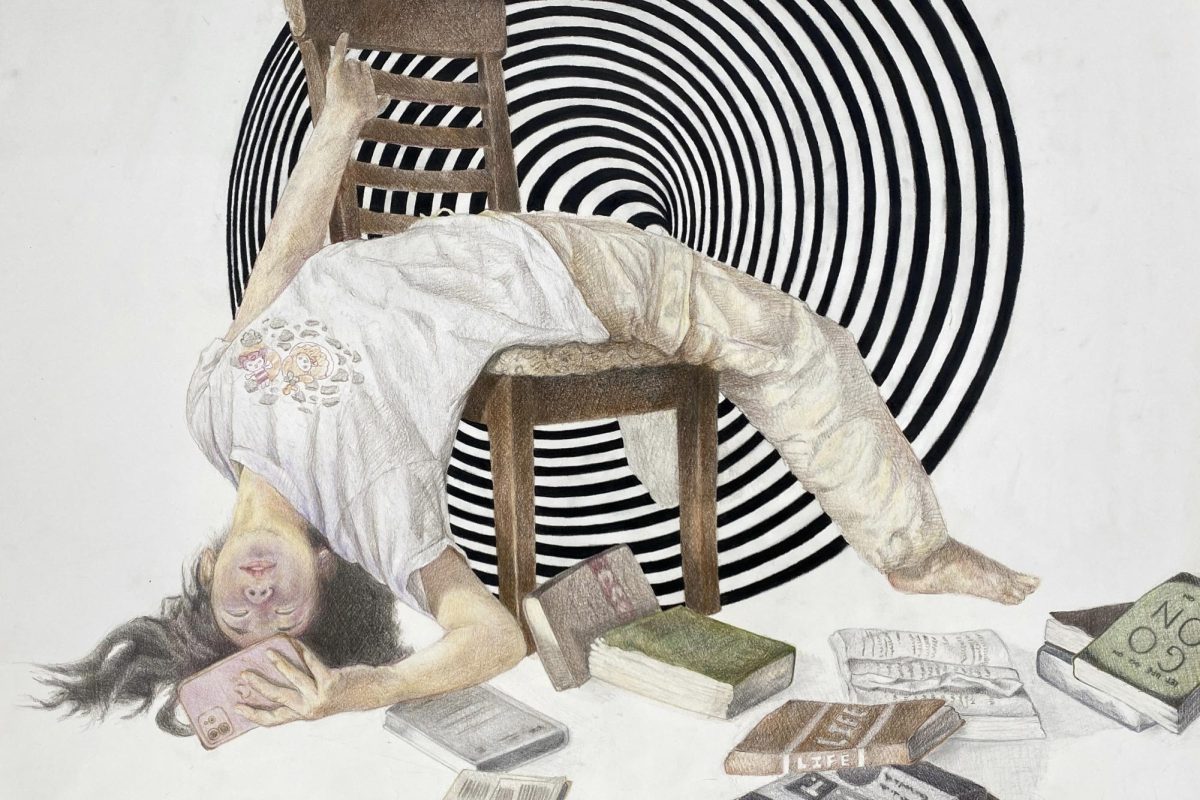

Although Francis and Goldstone have received initial positive feedback from the community, some are uncertain as to whether this class might not only be ineffective in terms of giving students a better understanding of race, but could even have a detrimental impact. Junior Prash Subbiah used an experience in middle school where students were educated on microaggressions as reasoning for why students will not respond well to the mandatory class.

“In middle school [they gave us an] equivalent to an extended advisory on microaggressions,” Subbiah said. “It struck me afterwards that people were just treating it as a joke. People were pretending to micro-aggress in a way that they weren’t before. I didn’t feel like I was the victim of constant microaggressions as a person of color before that lecture. After that, it sort of brought it to the front of everyone’s minds when it didn’t need to be.”

Discussions about whether schools should educate students on subjects such as race or gender have become increasingly divisive. Several states have banned or restricted these conversations from schools amidst massive political backlash. Many Americans reject classrooms as a setting for students to learn about and discuss social issues.

“People think that public schools are the solutions to all their problems,” Subbiah said. “They are the solution to many problems, but they are not the solutions to all problems, and so trying to effect social change through public schools is always going to cause a backlash.”

Despite the controversy of teaching about social issues in many parts of the country, Francis and Goldstone have received almost entirely positive responses in meetings with administration, as well as from the broader community through social media posts. In a 2020 survey, Wayland community members submitted suggestions of subjects to include in the class, which Francis and Goldstone intended to use as feedback to help shape the class with the experiences of people in Wayland.

“It’s a little bit scary to know that we’re getting yeses and enthusiasm, but then [this proposal] has been done [before], and I’m sure they got the same level of enthusiasm and then it just kind of died down,” Francis said. “That’s the fear that we have.”

Francis and Goldstone are not the first to propose a mandatory class for freshmen that would teach students to build skills beyond traditional curriculum. In 2020 up until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, drama teacher Aidan O’Hara introduced Freshman Life and Identity Practicum (FLIP), a class primarily taught by O’Hara that would replace freshmen seminars starting from second semester. The curriculum was based on teaching classes about identity and community, with the goal that the common experience would help freshmen with communication when discussing serious topics.

“Whether it’s middle school, high school or college, [making a] starting point by having those conversations is only going to make the community that much more vibrant and dynamic, and empower all the different members of that community to have a voice and to express themselves, and to do so with respect,” O’Hara said.

For years, there have been previous attempts to develop classes with similar goals as Francis and Goldstone’s. Goldstone describes the process of working within the education system to create a mandatory class as “millions of hoops you need to travel between.”

“I do think Wayland has been trying for a lot of years to actually make progress in this area. It’s just that progress comes really slowly within a school system,” Goldstone said. “Frankly, a lot of people, including myself, get very impatient with it because we’re ready for the change now, but it’s difficult when you’re working within the confines of the educational world. It’s just a matter of if we have people on the ground who really are passionate and care enough to make that progress.”

Since Francis and Goldstone have graduated and left the Wayland school system, staying involved in the process has become more challenging. Francis and Goldstone hope to take a step back and invite others in Wayland to take on roles in the project, allowing current students with similar passion to continue the momentum of their efforts.

“Ultimately this class is a collaborative class. I would love for [creating it] to be a collaborative process,” Francis said. “I would love [for] students to reach out to me if they want to see the work that we’ve done so far and if they want to take over. I would love to be a resource in any way that I can. We’re looking for passion in any shape or form. If anybody wants to support in any way, please [reach out]. It is accepted and needed.”

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)

![Troy Hoyt finishes the Boston Marathon, running for the Hoyt Foundation. T. Hoyt is the son of Hoyt Foundation CEO Russ Hoyt.

“[Running a marathon] might seem like a big thing, when it’s presented to you at first, but if you break it up and just keep telling yourself, “Yes, you can,” you can start chipping away at it. And before you know it, you’ll be running the whole 26 miles, and you won’t even think twice about it.” T. Hoyt said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/C36E8761-1CBB-452E-9DF2-543EF7B1095E_1_105_c.jpeg)

![WHS alumni Lizzy Francis and Sam Goldstone began the process of creating a stand alone race class for freshmen in 2020. “I think that a large issue with this country in general, honestly, is just [people] being uneducated and being unaware of different experiences,” WHS alum Lizzy Francis said. “I think that [by] bringing awareness to these social situations, we become better people, and we create a new generation of people that are kinder to each other, willing to listen and willing to be advocates for those who can't be advocates.”](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Screen-Shot-2022-06-16-at-4.22.47-PM-900x597.png)