One year later: Russian and Ukrainian students speak on the war’s impact

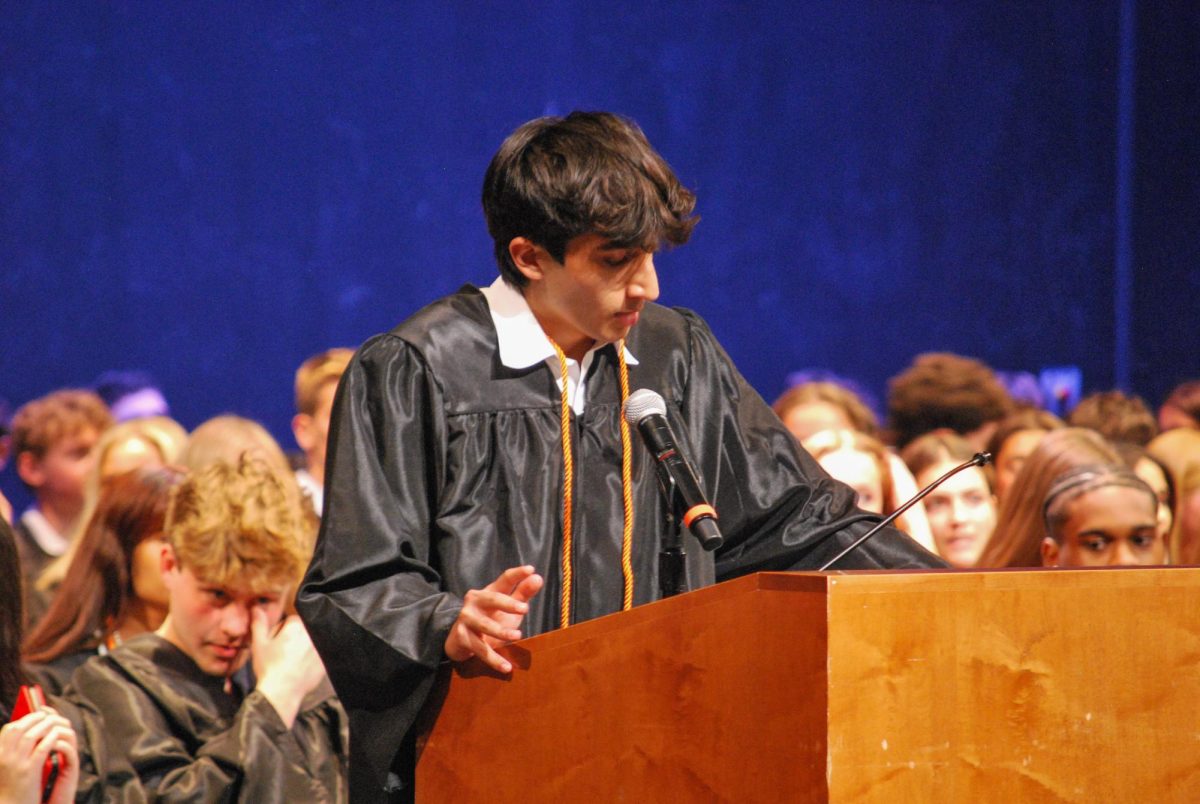

Credit: Alyssa Ao

Made by the current events class last school year, a display on the Russia-Ukraine war hangs in the History Wing. The display has since been taken down, as over a year has passed since the war began. “This war shouldn’t have started,” junior Misha Eberle said. “Nobody should have to die over these geopolitical forces that are just playing a game of chess. These [people] are just pawns in the game. So every death in this war is a tragedy.”

April 19, 2023

On Feb. 24, 2022, Russian military forces began their full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In what Russian President Vladmir Putin calls a “special military operation,” multiple cities have been bombed, including Ukrainian capital Kyiv, shattering the Ukrainian infrastructure and displacing millions of Ukrainian citizens. The war, which has been occuring for over a year now, has taken well over 350,000 lives, though the exact death toll remains unknown.

It has also been over a year since Wayland Student Press Network interviewed three students at Wayland High School with Ukrainian or Russian heritage about the war. Back then, the potential effects of the war had mostly been left to speculation, but now, these students have been able to grasp the long-term impacts the war has had on themselves, their families and their familial countries.

From severed connections with meaningful places to having to support family members still living in affected countries, the war has impacted Ukrainians and Russians all around the world. So far, more than 6 million Ukrainians have been displaced within the country, and another 8 million have fled as refugees to other European nations.

Most of WHS sophomore Alex Dremov’s extended family lived in Ukraine, until recently. Dremov’s cousins fled Ukraine when the fighting reached their doorstep and the situation became too dangerous for them to stay. They now live in Germany, where they are adapting to a new lifestyle away from home.

“It’s not easy to fit in [as refugees], and my cousins, they’re even younger than I am,” Dremov said. “They have to go to school, and that’s not really an option when you don’t speak German. Even if you do speak German, you’re going to be limited to an all ‘refugee school.’ So they’re going to be struggling with that.”

Last year, when the war was just beginning, junior Katya Luzarraga’s mother’s family, which is Ukrainian, planned to stay in Kyiv and help the war effort in any way they could. They now live in Newton, MA, near Luzarraga’s grandparents. Luzarraga’s mother keeps in touch with them to check in and see how they are adjusting to their new lifestyle.

“[My family left Ukraine] after all of the initial bombing stopped,” Luzarraga said. “I think any family that could escape chose to, or they chose to help and fight. My grandma helped [our family members] get set up with school for their daughters and paperwork that they wouldn’t [have been] able to do because they don’t speak English.”

Junior Dima Bobrov has friends his age in Russia who he often uses the internet to communicate with. However, restrictions in the country on certain social media have increased. Early in the war, Russia fully banned Facebook and Instagram, companies by Meta, which Putin referred to as an “extremist organization.” As a result, the young people of Russia are upset with their government and feel disconnected from the world.

“Everything that makes up the life of an American teenager is similar to the Russian teenager, but they’re basically having that stolen,” Bobrov said.

While the Russian government, also referred to as the Kremlin, has banned some social media platforms within the country, it uses other platforms, such as Telegram, to spread state propaganda. From deepfake videos of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, to forged documents and warnings about Ukrainian bioweapons, Putin has been able to sow pro-Russian sentiment within his country and around the world. In countries like the U.S. and France, far-right groups and news channels have spread this Russian propaganda to perpetuate their own conspiracies and political agendas. But despite Putin’s efforts, the younger population of Russia, which still has access to western media, does not fully support him.

“A lot of the [people in the] younger generation in Russia, especially in the big cities, are way more anti-Russia,” junior Misha Eberle said. “They support a closer connection to Europe, which makes sense because they’re more connected with the internet.”

Despite the disapproving younger sentiment, Putin’s propaganda has served him by convincing the older generation, who don’t have the same access to varying sources of information like their younger counterparts. According to Bobrov, many of those in the older generation are experiencing a “Soviet Nostalgia.” The messages the state is feeding them are similar to the ideas they heard while living under the Soviet Union, which collapsed in 1991. Eberle’s grandmother, who lives in Russia, has been watching the Russian news, and supports the Kremlin’s actions. She has been exposed to these ideas through media.

“[My grandmother] of course does want the best for the Ukrainian people,” Eberle said. “She’s good-hearted in that regard. She cares for them, but she thinks they’d be better off under Russian rule, not under the government they are now.”

Bobrov has family living in Crimea, a Russian-occupied Ukrainian territory, and in St. Petersburg, Russia. All of his family members in both places have remained at their homes since the beginning of the war. Bobrov, who frequently went to Russia before the war, has kept in touch with family and friends his age there. While he tries not to discuss the war with friends often, Bobrov said that the topic of the Russian government sometimes comes up naturally in conversations, as its actions have become intertwined with Russian life.

Even though Bobrov is living in America, he isn’t exempt from the Russian government’s policies. Russia has had a conscription army for over a century, and currently, all male Russian citizens aged 18-27 are subject to the semi-annual draft and typically serve one year of active duty. Bobrov, who is 17 years old, is a Russian citizen, meaning he will soon be liable for military service.

“Russia is very important to me, and I want to go there soon,” Bobrov said. “This summer it’s very important that I go because I have a military conscription coming up. When I turn 18, I have to join the military if I go to Russia.”

Russian conscription laws have changed since the beginning of the war. Putin amended legislation to allow conscription of citizens with serious criminal records. The Wagner Group, an organization of Russian mercenaries, has been drawing the bulk of its soldiers, who are often killed in large numbers, from prisons. Ukraine on the other hand, with a population about a third the size of Russia’s, has been deploying citizens from all walks of life. The Kremlin’s choice to send citizens like convicts, whose lives may be viewed as less valuable, could give insight into Putin’s war tactics.

“[The Russian government is] trying to minimize casualties, obviously, because having a bunch of casualties, I mean, that would just be horrible for Putin because he invaded first,” Eberle said. “Everybody would just be pointing the finger at him and his country, [the] people of Russia would be very mad at him.”

Russia is not drafting most average citizens. This means Eberle’s family doesn’t have to worry about being sent to the front lines, at least for now.

“I heard that my uncle might get conscripted [into] the war in Ukraine,” Eberle said. “I don’t think that was really possible. But if the war escalates, it is very possible.”

The flood of Russian propaganda and military force didn’t begin in February of 2022. Russian military build-up on the Ukrainian border started nearly a year before the invasion. Ukrainian and Russian students at WHS have been aware of the tensions between the two countries since the Maidan Revolution in 2014, which was followed by Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and fighting by pro-Russian separatists against the Ukrainian government. Since then, the conflict has continued to escalate until Russia ultimately invaded Ukraine.

Luzarraga recalls hearing about the conflict all throughout her childhood. Bobrov, Dremov and Eberle all agree that despite the war’s long duration, barely any progress has been made on either side.

“It just feels like so much has happened, and nothing has really changed apart from all of the lives that have been lost,” Dremov said. “I don’t really see the point in the conflict. It just feels kind of pointless. And long before [Russia sent troops to Ukraine], there was a conflict between Russia and Ukraine. It’s been going on for that entire time since then. It’s just a very long conflict and it doesn’t seem like it’s gone anywhere.”

The students also have to decide whether or not to expose themselves to more information about the war. While Bobrov has been following the events in Ukraine and Russia closely, Luzarraga researches the conflict less now than she did at its beginning, as she feels the news doesn’t show positive developments.

Dremov’s grandparents are currently living in Donetsk, one of the Ukrainian cities where much of the conflict is taking place. For Dremov, the war has become another source of stress that has fallen into place alongside other aspects of his life. When his mother talks to his grandparents via Skype, they try to keep their conversations mostly positive. However, when they do discuss the conflict, Dremov tries to not listen in.

“They try to keep it as lighthearted as possible because it’s a sad topic to discuss,” Dremov said. “So they try to avoid the topic of war and they just talk about daily life. My mom keeps bees and my grandparents keep bees, so they talked about that. And they both liked gardening. So it’s kind of like, you know, just small talk.”

The war has been going on for over a year, and it still continues to affect the lives of millions of people. Whether it’s worrying about loved ones living near the warzone or family members becoming refugees and having to adapt to their new lives, the war has had a profound impact on Ukrainian and Russian students, even from the other side of the world.

“Russia was such a key part of my life,” Bobrov said. “When I was a kid, I went every single year in the summer. I would spend all three months of summer in Russia, and it was just a key part of my identity. To not be able to go there, to have everything I know about it flipped on its head, it’s definitely been affecting me mentally.”

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)

![Troy Hoyt finishes the Boston Marathon, running for the Hoyt Foundation. T. Hoyt is the son of Hoyt Foundation CEO Russ Hoyt.

“[Running a marathon] might seem like a big thing, when it’s presented to you at first, but if you break it up and just keep telling yourself, “Yes, you can,” you can start chipping away at it. And before you know it, you’ll be running the whole 26 miles, and you won’t even think twice about it.” T. Hoyt said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/C36E8761-1CBB-452E-9DF2-543EF7B1095E_1_105_c.jpeg)

![Made by the current events class last school year, a display on the Russia-Ukraine war hangs in the History Wing. The display has since been taken down, as over a year has passed since the war began. “This war shouldn't have started,” junior Misha Eberle said. “Nobody should have to die over these geopolitical forces that are just playing a game of chess. These [people] are just pawns in the game. So every death in this war is a tragedy.”](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Screen-Shot-2023-04-05-at-8.36.02-PM-900x600.png)

Kedar • Apr 19, 2023 at 10:40 AM

Excellent article and work done by authors. It’s a very important and sensitive issue for the world. Providing free voice for teenagers who have families or friends living in both these countries helps everyone to understand diverse perspectives. Best wishes