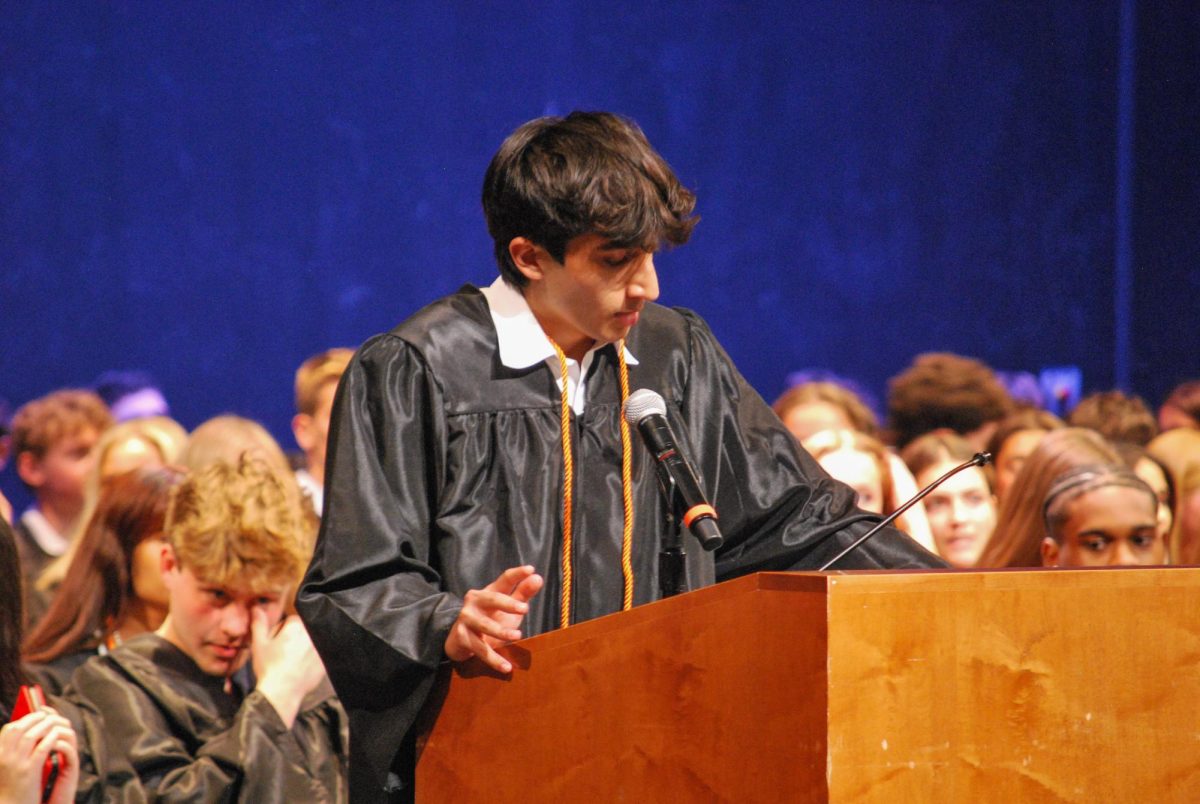

Kyle’s Column: “Chemistry” and being Chinese-American

In the latest installment of Kyle’s Column, Opinions Editor Kyle Chen reflects upon lessons from “Chemistry,” the debut novel of Chinese-American author Weike Wang.

January 31, 2020

There’s a passage in “Chemistry,” the debut novel of Chinese-American author Weike Wang, that goes:

“Here is a joke a classmate tells me in middle school: When an Asian baby is born her parents hold up two signs, ‘Doctor’ and ‘Doctor,’ and the baby must choose.

By now, I have heard many versions of this joke. Times change, so no longer ‘Doctor’ or ‘Doctor,’ but ‘Doctor’ or ‘Scientist.’ ‘Doctor’ or ‘Engineer.’ ‘Doctor’ or ‘Investment Banker.’

It isn’t so much of a joke as a statement.”

Wang exaggerates, to be sure. But as crude (and, for the most part, inaccurate) as the joke may be, like all jokes, it is rooted in truth. My parents never held up signs when I was born, nor have they forced me into wanting to be a doctor (or investment banker). Yet they have raised signs – albeit unconsciously – that have set me on a kind of preordained path in life.

Both of my parents were born and raised in poverty in rural China. Like many others, they started with nothing – their families were farmers and peasants of the post-Cultural Revolution era. They were both first-generation college students, and they worked incredibly hard just to earn the educational opportunities they had. There’s a reason Chinese culture today is known for its emphasis on education – many Chinese, my parents included, achieved everything through it. Education was their means of upward social mobility – hard work at school netted them the opportunities to attend college, and for many, their degrees gave them the opportunity to emigrate to the U.S. and create a better life for themselves and their children.

As the children of these immigrants, my generation has inherited this paradigm of hard work, perseverance and success through education. From a young age, we are taught to study hard and strive for the top colleges, where we could earn degrees that could lead us to stable, productive lives. Our parents, involuntarily or not, indoctrinate us with the idea that this is the road to success, the path that we have no choice but to follow.

On the surface, there’s nothing wrong with this tried-and-true model of “achieving success.” Yet its implications for many first-generation Asian-Americans cannot be ignored. Even if it is a work of fiction, I think “Chemistry” has something important to say about the effects of our indoctrination.

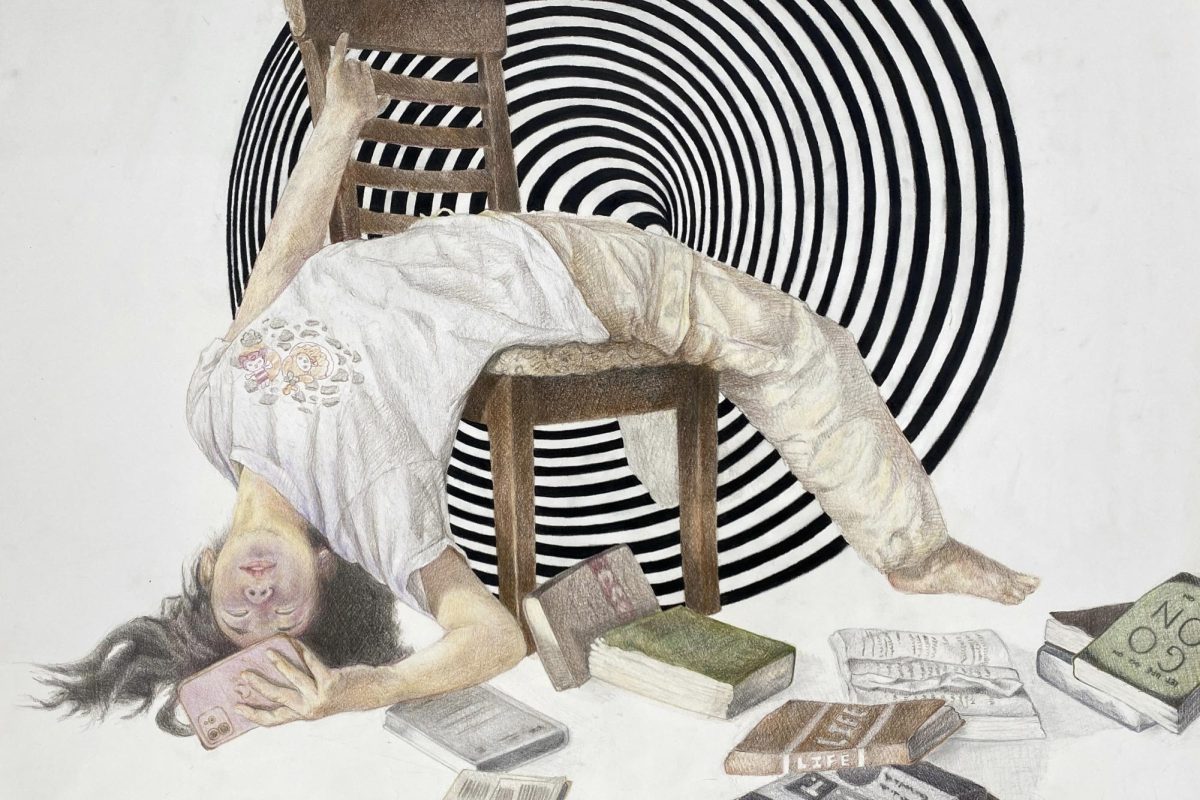

Wang – who was born in China and immigrated to the U.S. at the age of five – tells the story of an Asian-American graduate student who is pursuing her doctorate in chemistry. Up until this point, the student has scored top marks, effortlessly acquiring and applying the knowledge she was taught. But now she must make a contribution to the field – to create knowledge rather than just consuming it. She is at a loss – all her life, she had followed the knowledge of others, and when it comes time to create something of her own, she comes up blank.

Perhaps the struggle of Wang’s chemistry student embodies the inherent dangers of the paradigm we first-generation Asian-Americans inherit from our parents. By blindly following the road that’s been set out for us, we risk losing sight of what matters to us as individuals. Though we may find financial stability and material success, we could very well be sacrificing our happiness and fulfillment in the process. Ultimately, this doctrine of collectivized success is, in a sense, incompatible with the principles of individualism, fundamentally at odds with the essence of the American dream. By following a well-trodden, defined path, we may lose the opportunity to create and live a meaningful existence for ourselves.

Here’s a final quote to think about:

“My father’s is the classic immigrant story.

He is the first in his family to go to high school and college and graduate school and America. He is the first to become an engineer.

Extraordinary, some people have said when he speaks of how he got here.

Through hard work, he says, and the learning of advanced math.

Amazing, others have said.

But such progress he’s made in one generation that to progress beyond him, I feel as if I must leave America and colonize the moon.”

For me and many of those who represent the first in a new cultural heritage, our parents are the pillars that anchor and guide us, the lenses through which we learn to see the world. I will always appreciate all that my parents have given and taught me, but I must set off from the beaten path. As Wang said, I cannot progress beyond them by colonizing the Moon – and at the end of the day, maybe I don’t have to. Whatever happens, I’ll find my own way.

Opinion articles written by staff members represent their personal views. The opinions expressed do not necessarily represent WSPN as a publication.

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)

![Troy Hoyt finishes the Boston Marathon, running for the Hoyt Foundation. T. Hoyt is the son of Hoyt Foundation CEO Russ Hoyt.

“[Running a marathon] might seem like a big thing, when it’s presented to you at first, but if you break it up and just keep telling yourself, “Yes, you can,” you can start chipping away at it. And before you know it, you’ll be running the whole 26 miles, and you won’t even think twice about it.” T. Hoyt said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/C36E8761-1CBB-452E-9DF2-543EF7B1095E_1_105_c.jpeg)