“Left on Pearl” offers insight to the Women’s Liberation Movement

Credit: Joanna Barrow

The Women’s Center of Cambridge is located at 46 Pleasant Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This has been the location for the Center since its opening in 1971. The founding women used money raised through the takeover to put a down payment on the property.

May 28, 2020

In a small, suburban town such as Wayland, the term “women’s center” may be lost on the average high school student. But 17 miles east of Wayland resides the oldest community-based center for women in the United States. It’s a four story home with a living room, library, kitchen, computer labs, garden and art spaces that serves as a refuge for all who identify as women, especially for those who are vulnerable, low-income and socially isolated in the Cambridge and Greater Boston area. Nearly 50 years ago, this idea of a space in society carved out just for women was a radical idea, and it took radical measures to make it.

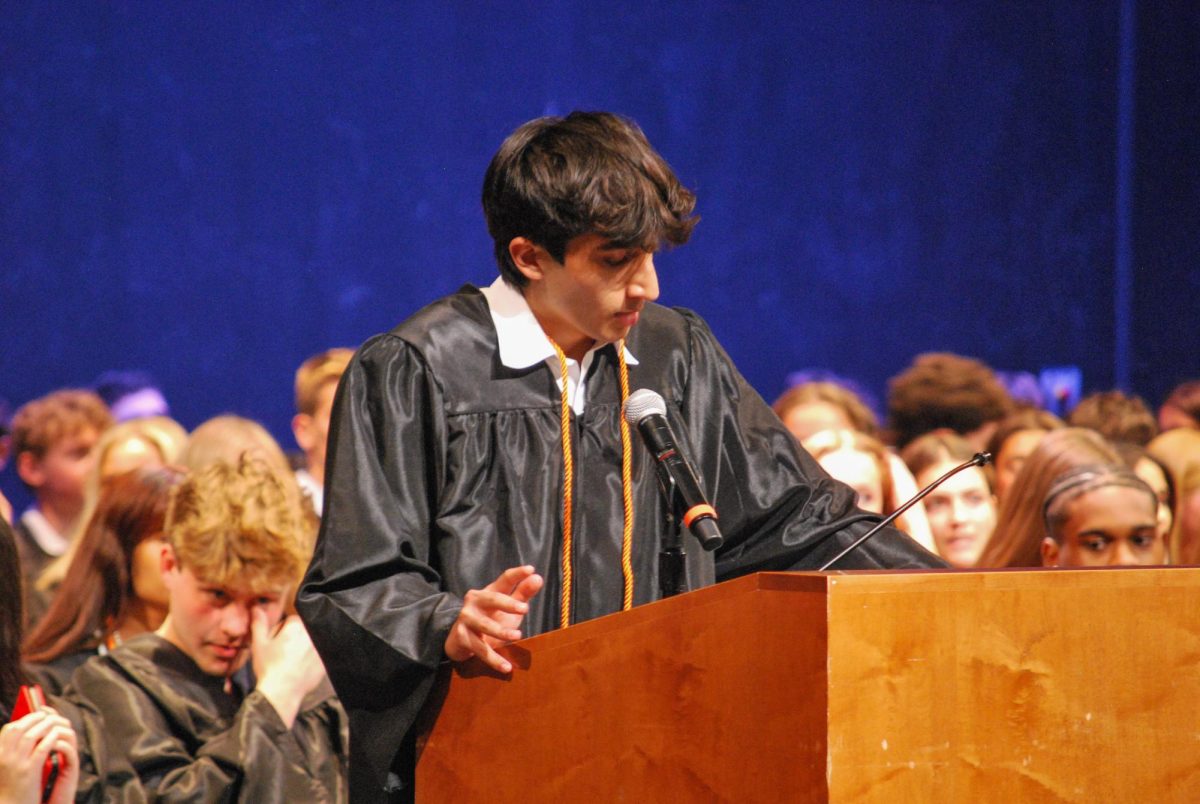

Only a few days after International Women’s Day on March 8, the Wayland Library hosted a screening of the documentary “Left on Pearl Street,” a 55 minute look into a moment in the Women’s Liberation Movement. When marchers in the 1971 International Women’s Day parade seized a Harvard University owned building and claimed it as their own, it became a 10 day take-over that culminated in the founding of the Cambridge Women’s Center.

Library foot traffic had slowed by the scheduled start time of the film, and it had just been announced that Claypit Hill Elementary and the Wayland Middle School would close the following day due to the Coronavirus. But in the Raytheon Room located in the basement of the library, a modest group of viewers had gathered to watch “Left on Pearl Street” and participate in a Q&A with one of the film’s executive producers, Susan K. Jacoby.

“The takeover happened in 1971, so people should really think about it as part of the 60s,” Jacoby said. “[To fully understand the event], you need to understand the ’60s.”

The Wayland Public Library hosted a screening of the documentary “Left on Pearl Street” on March 8. The film details the 1971 occupation of a Harvard University owned building, located at 888 Memorial Drive, in order to establish the first Women’s Center in the Boston area. The event was a crucial point in the Women’s Liberation Movement and is nowadays often overlooked.

In the tumultuous decade that was the 1960s, the United States was undergoing a cultural revolution. The Antiwar Movement, condemning the Vietnam War, fueled the Countercultural Movement. The Civil Rights Movement was at its height in the 60s, and after a period lying dormant, a second wave of feminism began the Women’s Liberation after Betty Friedan published “The Feminine Mystique.”

As it says in the extended summary of the documentary on the “Left on Pearl” website, “in 1971, classified ads for employment were still segregated by gender, battered women’s shelters did not exist, abortion was illegal and a married woman couldn’t open a bank account without her husband’s permission. ‘Left on Pearl’ is about the movement that changed all that.”

About the film, Jacoby said in her opening remarks, “It explores some of the myths about second wave feminism.”

After her introduction concluded, Jacoby left the podium beside the drop down projection screen. Then, the lights were dimmed and the film began to the track of Big Brother and the Holding Company’s “Piece of My Heart.”

During the March 6 International Women’s Day parade in 1971, a group of 150 women–a coalition from different backgrounds and ideologies–turned left on Pearl Street, breaking from the expected march route downtown and seized what used to be Harvard University’s Architectural Technology Workshop at 888 Memorial Drive. It had been slated for demolition in a plan to expand housing for students and faculty of Harvard. They dubbed the building the “Liberated Women’s Center.”

The group of organizers included women from organizations that existed at the time like the Bread and Roses, the Old Mole Women’s Caucus and Gay Women’s Liberation.

At the same time, a group of activists called the Riverside Planning Committee opposed Harvard University’s expansion, as it would uproot already established communities. The activists were demanding that Harvard create more affordable housing in the nearby community of Riverside. Specifically, they had demanded that 888 Memorial Drive be converted into affordable housing just one year prior.

Riverside Planning Committee leader, Saundra Graham, met with the coalition of women and they added affordable housing for the Riverside community to their list of demands.

During the next 10 days of occupation, women from all walks of life gathered in the Liberated Women’s Center to find solidarity in one another. Free childcare was offered, as were health classes, karate classes and mechanic classes. Women danced and cut their hair in acts of liberation and the Harvard Crimson reported that at the time of the event, the women were “joyous” and lesbian couples expressed themselves freely.

An image of the 888 Memorial Drive standing today. The building that housed the takeover was knocked down, and in its place is now a park before Harvard graduate housing. There is now a different building in the exact location of the former architectural building that has the address of 10 Akron Street.

The women left the building on March 15, 1971 after rumors of a police bust and a vote for their eviction. The group left together, chanting and singing, their faces painted and carrying banners.

The chair of Harvard Radcliffe’s Board of Trustees, Sue Lyman, donated $5,000 (equivalent to $30,000 in today’s dollar) to the group of women who then used that money to put a down payment on the house that is now the Cambridge Women’s Center. The center would go on to establish Boston’s Rape Crisis Center, the first shelter for assaulted women in Cambridge. Today, they offer a variety of programs to support the women who walk through their doors.

Once the documentary had ended, the promised Q&A session began and soon turned into a conversation about how the movement has evolved over the decades. One participant brought up how the workforce has seen a remarkable change.

“We’ve become an army of occupation rather than an army of conquest,” the participant said.

The participant argued that women’s liberation has shifted to focus primarily on their careers, but someone else countered that there was still far to go.

There were arguments that the movement has stalled and lost the fervor of the second wave, and that the movement has seen significant changes in the past five to 10 years because of the #MeToo movement, which caused a cultural shift in how consent is viewed.

At one point, Jacoby thumbed through a folder she had with her, withdrawing and unfolding a slip of paper.

“I can read you the demands they made,” Jacoby said. “Let’s see how many of them we’ve got.”

One: free medical care and access to abortions and The Pill. Two: equal pay. Three: put an end to the proliferation of degrading images of women. Four: free child care. Each demand was punctuated with a look from Jacoby that the room seemed to understand. These demands have yet to be fulfilled.

A general consensus was formed: a lot has changed, but a lot hasn’t.

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)

![Troy Hoyt finishes the Boston Marathon, running for the Hoyt Foundation. T. Hoyt is the son of Hoyt Foundation CEO Russ Hoyt.

“[Running a marathon] might seem like a big thing, when it’s presented to you at first, but if you break it up and just keep telling yourself, “Yes, you can,” you can start chipping away at it. And before you know it, you’ll be running the whole 26 miles, and you won’t even think twice about it.” T. Hoyt said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/C36E8761-1CBB-452E-9DF2-543EF7B1095E_1_105_c.jpeg)