Opinion: In public service, retirement shouldn’t be a choice

Credit: Courtesy of Flickr user davidleesf

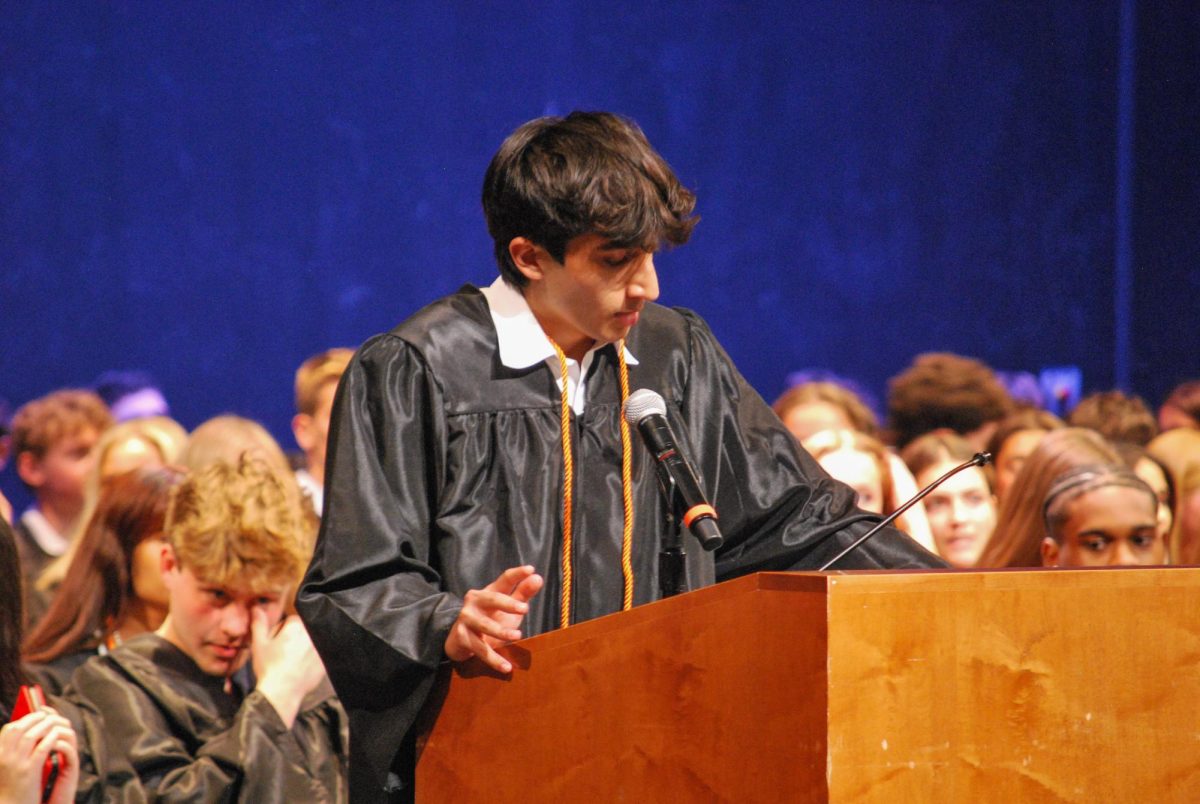

Guest writer Prash Subbiah discusses the dangers of senior citizens holding public office.

The nature of politics inherently advantages candidates from certain demographic groups. In recent times, Congress and state legislatures have done a slightly better job of reflecting the increasingly diverse racial and ethnic makeup of the nation, yet the presidency and governorships continue to be almost as white and as male as ever. These disparities are widely talked about and well-documented. In the shadow of other demographics fighting for equal representation in government, hides another underrepresented minority: young people.

In 2016, America elected the oldest president in its history. Four years later, dissatisfied with its selection and with the current state of affairs, America chose to replace Donald Trump. Whom did it choose? Someone even older.

The harsh reality is that in the private sector, a 78-year old (or 75-year old, for that matter) seeking a new job would be unemployable. An applicant nearly double the median age for an American likely lacks the current skills and mental faculties to do their job as effectively as their younger counterpart. Most people’s cognitive capabilities peak in their twenties, with gradual decline thereafter. There’s no doubt that there are exceptions, octogenarians who are as sharp as they were in their youth, but it doesn’t seem to be the case that these elderly politicians are, indeed, exceptions. Whether it be Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley’s deranged tweets, California Senator Dianne Feinstein asking Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey the same question twice having seemingly forgotten what she just answered, or even former President Trump’s infamous “covfefe” and “person, woman, man, camera, TV’ incidents, seniors in office haven’t been especially successful in demonstrating that they aren’t yet past their sell-by date.

Perhaps the most offensive aspect of such displays of unfitness for office is that each of the aforementioned politicians continues to cling to power. Senator Grassley, 87, is entertaining the possibility of a reelection campaign in 2022 for a term that would take him well into his nineties, Senator Feinstein, 88, is rejecting calls from constituents to resign, and all signs point to another presidential run from former President Trump in 2024.

Setting aside arguments about fitness for office, a fact too often ignored, is that young people have interests fundamentally differing from the old, and those interests are almost without exception neglected by policymakers. By the time we experience the full effect of climate change, for example, our oldest politicians will be, quite frankly, too dead to be bothered. Maybe that’s the reason everyone but the most progressive in Congress deems a carbon tax too damaging to the economy to warrant serious consideration— as if the flooding of the New York Stock Exchange would act as an economic stimulus. But it isn’t just climate change. If the non-elderly weren’t so underrepresented, maybe proposals such as those to guarantee paid parental leave or to make college more affordable would be given a second look.

Even without the demographic skew in terms of age that is present in politics, retirees and pensioners would still have outsized power. Young people simply don’t vote at the same rate as their elders. To some extent, we made our bed in that regard, yet it nonetheless heightens the need for younger politicians.

Despite all this, the electorate, which includes young people, continues to nominate and elect politicians well into their later years for the most powerful offices. This isn’t because voters want experience in their candidates: the election of Donald Trump should have dispelled any notion that one needs experience to be elected. Rather, voters seek candidates whose name they recognize. Hillary Clinton may well have been the most qualified candidate for president in history, but she wasn’t especially popular, even with Democrats. She won the Democratic nomination because she was the most recognizable candidate. And there lies the problem: while Joe Biden was serving as vice president of the United States, Pete Buttigieg was serving as Mayor of South Bend, Indiana. Now-Secretary Buttigieg wasn’t even born when Biden was first elected to the Senate and when Trump started to gain celebrity status.

Plenty of people liked ‘Mayor Pete’. So many that he won the Iowa Caucuses. He even went on to place second in the first primary in New Hampshire, yet the rest of the race proved less successful. Buttigieg was initially propped up by the ability to spend months campaigning and millions of dollars in the states that were first on the calendar: Iowa and New Hampshire. As the mayor of a college town in Indiana, getting the entire country to know his name in just a few months was always impossible. The people of Iowa, which got the opportunity to meet the candidates, picked Buttigieg. The rest of the country, comparatively in the dark, went for whom they knew: the 78-year old Biden or the 79-year old Senator Bernie Sanders.

There is no way to get Americans to vote for someone they’ve never heard of— nor should there be, but there is a solution to eliminate unfit and disconnected politicians who are surviving on name recognition alone: a mandatory retirement age for public office. The concept is hardly radical. The US military has a mandatory retirement age of 63, with only the most senior officers being allowed to go to 68. The Founders themselves put constraints on the age of public servants. The Constitution stipulates that one must be at least 25 to be elected to the House, 30 to be elected to the Senate, and 35 to become president or vice president.

Some would argue that setting a specific retirement age would be arbitrary, and they wouldn’t be entirely wrong; however, we already have an arbitrary number which the government deems a reasonable age for retirement. From the time we start earning money, each American has to pay into Medicare, and when you reach 65, the federal government allows you to start receiving benefits because you are too old to be working and thus can no longer rely on having employer-provided health insurance.

Some very capable politicians with the right priorities will undoubtedly be excluded from public office with a mandatory retirement, but no one can’t be replaced. If their ideology is something that their constituents truly believe in, an heir can and will be found. But, if, as is more often the case, it’s their name alone providing for their political survival, the people will finally be offered a new, and more able, representative.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Wayland High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, cover our annual website hosting costs and sponsor admission and traveling costs for the annual JEA journalism convention.

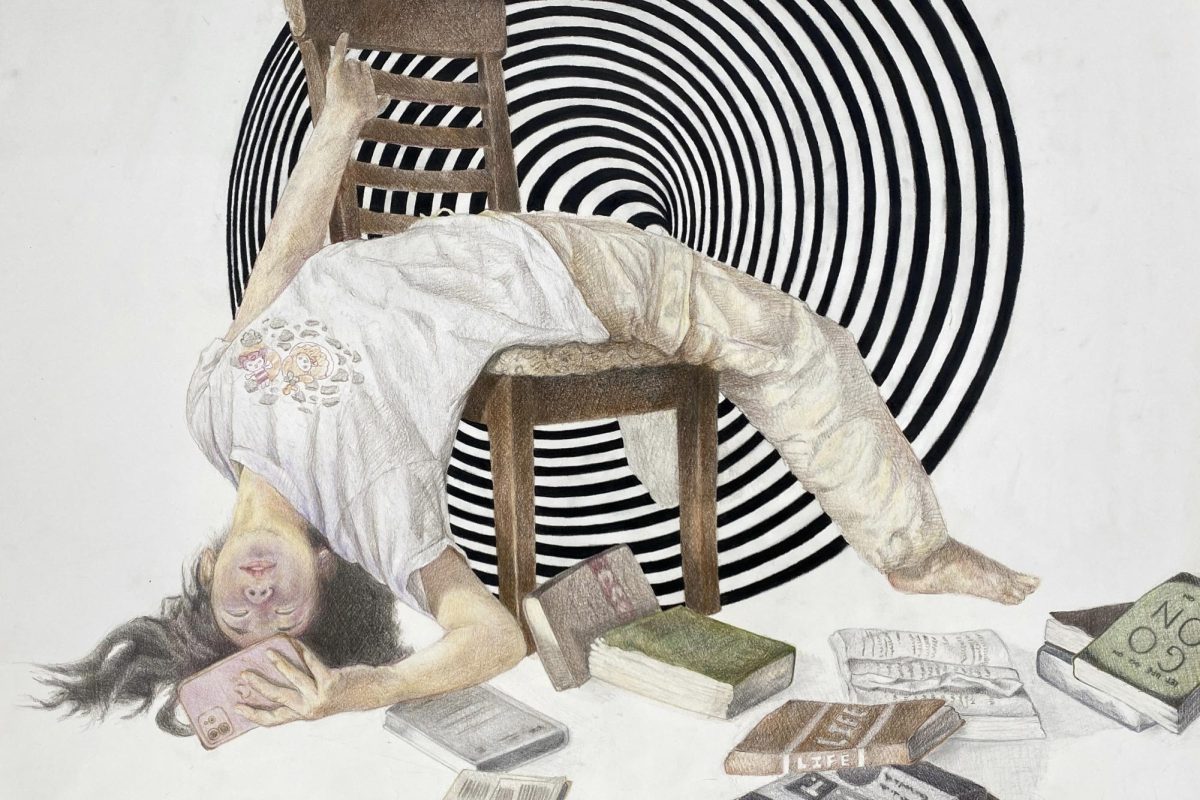

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)

![Troy Hoyt finishes the Boston Marathon, running for the Hoyt Foundation. T. Hoyt is the son of Hoyt Foundation CEO Russ Hoyt.

“[Running a marathon] might seem like a big thing, when it’s presented to you at first, but if you break it up and just keep telling yourself, “Yes, you can,” you can start chipping away at it. And before you know it, you’ll be running the whole 26 miles, and you won’t even think twice about it.” T. Hoyt said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/C36E8761-1CBB-452E-9DF2-543EF7B1095E_1_105_c.jpeg)