Transfer students adjust to their life in America

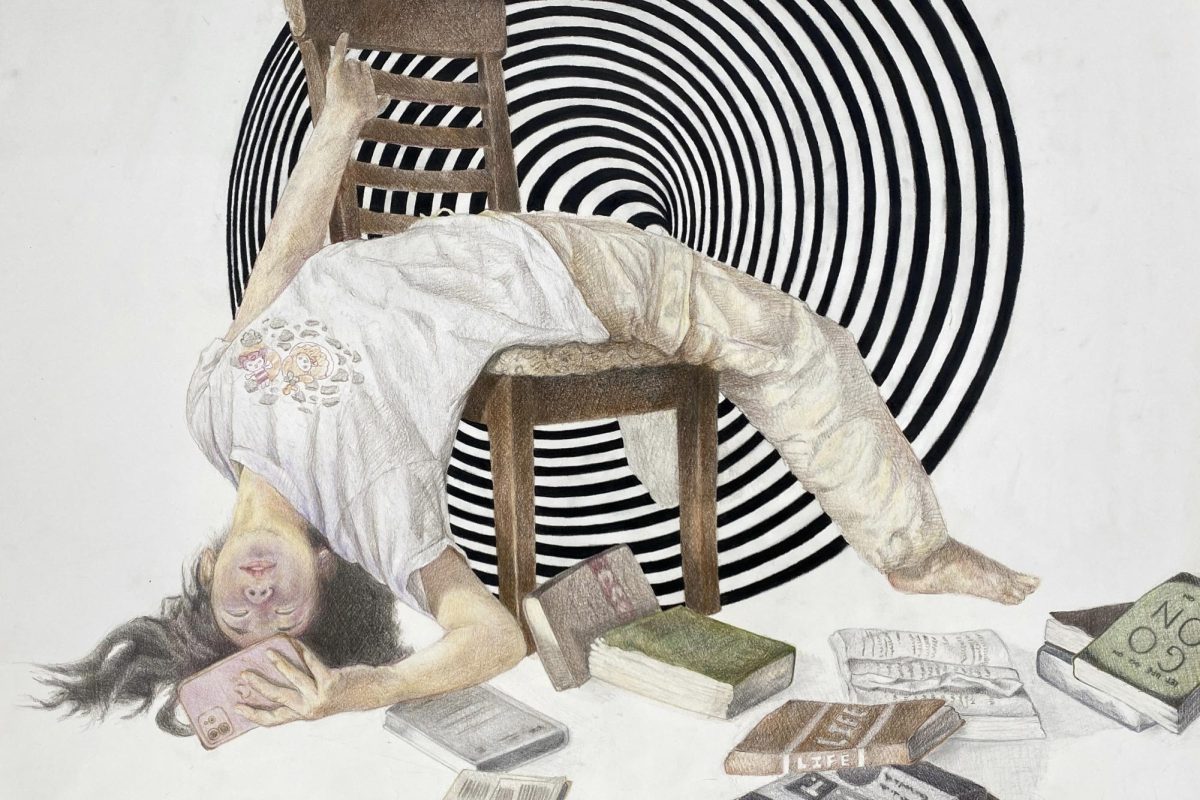

Credit: Courtesy of Miguel Kast Puga and Anna Guthmann

Junior exchange student Anna Guthmann and sophomore Miguel Kast Puga moved to Wayland in the middle of Aug. from countries outside of North America. The bottom image shows Kast Puga standing with his dad in Santiago, Chile, and the top right photo shows him with a friend. The top left image is from Guthmann’s school in Munich, Germany. Both have had to adjust to the new environment, academics and language change. “On my first day of school, a lot of people came up to me and introduced themselves,” Guthmann said. “It was really fun.”

December 16, 2021

Moving to a new school is already hard, as it comes with adjusting to a different environment. For some new students at Wayland High School this year, the move isn’t just into a new school district: it’s a new school, country and continent.

Junior exchange student Anna Guthmann and sophomore Miguel Kast Puga moved to Wayland right before school started. Guthmann came from Munich, Germany, and is staying with a host family for the school year. She plans to go back to Germany next year. Kast Puga moved from Santiago, Chile, in August for his dad’s work.

“I was happy because I applied for the scholarship two years ago,” Guthmann said.

Both Guthmann and Kast Puga come from countries where English is not the official language, so adjusting to the language change has been very hard. Not only is it challenging to communicate with people, but having to learn and write in English has added another level of difficulty.

“[In school] you need to be concentrated all the time, and I need to translate everything in my head,” Kast Puga said. “[Learning is] the hardest part.”

Along with the language differences, both have had to adapt to American school life. A big change for Guthmann was the length of the school day. In Germany, an average day of school lasts from 8:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. In Wayland, a typical school day starts at 8:35 a.m. and ends at 3:10 p.m.

“In Germany, [the school day is] really short,” Guthmann said. “You eat at home because we don’t have lunchtime at school. When I first came here, it was so exhausting to be here until 3:00 p.m.”

After school in America, most students choose to participate in a club or sport. At Guthmann’s school, there were no clubs or sports. For Kast Puga, his school offered fewer clubs, and sports were set up differently.

“Here, there are so many more options than in Chile for clubs,” Kast Puga said.

Kast Puga continued to play soccer in Wayland, as he was on the WHS boys varsity soccer team during the fall season. In America, sports have specific seasons. For example, soccer is in the fall, basketball is in the winter and outdoor track is in the spring. At his old school, a single sport would continue for the whole school year.

“In Chile, you have the same sports the entire year because there’s not as many changes in the weather,” Kast Puga said. “You can still play soccer in the winter outside because it’s not that cold. I played soccer the entire year there at my school. We usually trained four times a week.”

In Wayland, most sports have both a varsity and junior varsity team, some even with an additional freshman team.

“[In Chile,] we had one team per two grades, seventh and eighth grade, ninth and tenth and then eleventh and twelfth, so you only play with the same year as you and the [grade] below or above you,” Kast Puga said.

Furthermore, Kast Puga and Guthmann experienced some positive changes academically. In their past schools, teachers have been stricter. In Wayland, teachers have felt more helpful.

“In America, I have to say that here [teachers] feel more like a friend,” Guthmann said. “Of course they are teachers, but they are nicer. In Germany, they can be really strict.”

Kast Puga has similar thoughts on the difference between teachers at his old school and WHS.

“The teachers here are better because they want to help you more than the teachers in Chile,” Kast Puga said. “If you ask a teacher in Chile to help you because you don’t understand the subject, they do not always pay attention to details, such as a student falling behind the rest of the class.”

Grading in Wayland is on a letter scale. Students may receive either an A, A-, B+ and so forth for a specific subject based on the corresponding percentage to that letter. While in other parts of the world, grading is on a scale of numbers. For Kast Puga, the scale was from 1 – 7, and for Guthmann the scale was from 1 – 6.

Both have found that getting a good grade is much easier in Wayland than in their past schools.

“I think the grading is much harder in Chile because all of the tests are tricky,” Kast Puga said. “The teachers made it to trick you, so usually people don’t get near a 100%. It’s usually [in] the 80s or 70s [percent range].”

At most public high schools in America, the school schedule is structured so that students switch classrooms for every subject.

“In Germany, we had one teacher who taught us almost everything,” Guthmann said. “We don’t change classrooms, and the teacher can decide if we are doing math or something else. We didn’t really have a schedule, we just did what the teacher said.”

Kast Puga and Guthmann stayed with the same students in their class for the entire school year.

“Classes are in the same room with the same people the entire year, but almost all of the years, they change classes, [so] you’re not with the same people the entire time you’re in school,” Kast Puga said.

Kast Puga felt that sharing a classroom with the same students was a positive since he was able to know everyone better.

“The good part is that you know everyone really well in your class because the entire time you’re with them, so you get to know them really well,” Kast Puga said. “Here, where you switch from class to class, you don’t really know your classmates.”

At WHS, most core academic classes are offered at three different levels: principles, college preparatory, honors and advanced placement. At Guthmann and Kast Puga’s old schools, everyone was placed into the same class.

“I like having levels more,” Guthmann said. “Here, you can choose between intro, college and honors. In Germany, there is just one level.”

Kast Puga believes leveled classes allow students to learn at the right pace.

“Because you can have different levels here, if somebody is struggling with math, he can go one step back, and if you’re really good, then you can get better,” Kast Puga said.

Since Chile is in the southern hemisphere, the seasons are opposite of what they are here in the northern hemisphere, so Kast Puga’s school year was at a different time. In Massachusetts, most public schools last from late Aug. to the middle of June, with summer break in between.

“Our school year is from March to Dec.,” Kast Puga said. “Now, summer is starting [in Chile], so I see all of my friends going to the beach, and here it’s so cold.”

Overall, Kast Puga and Guthmann have been enjoying their time at WHS.

“The best part was the soccer season because it was something familiar, and it helped me get through the change,” Kast Puga said.

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)

![Troy Hoyt finishes the Boston Marathon, running for the Hoyt Foundation. T. Hoyt is the son of Hoyt Foundation CEO Russ Hoyt.

“[Running a marathon] might seem like a big thing, when it’s presented to you at first, but if you break it up and just keep telling yourself, “Yes, you can,” you can start chipping away at it. And before you know it, you’ll be running the whole 26 miles, and you won’t even think twice about it.” T. Hoyt said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/C36E8761-1CBB-452E-9DF2-543EF7B1095E_1_105_c.jpeg)