Smoke from West Coast wildfires spreads to New England

Credit: Emily Chafe

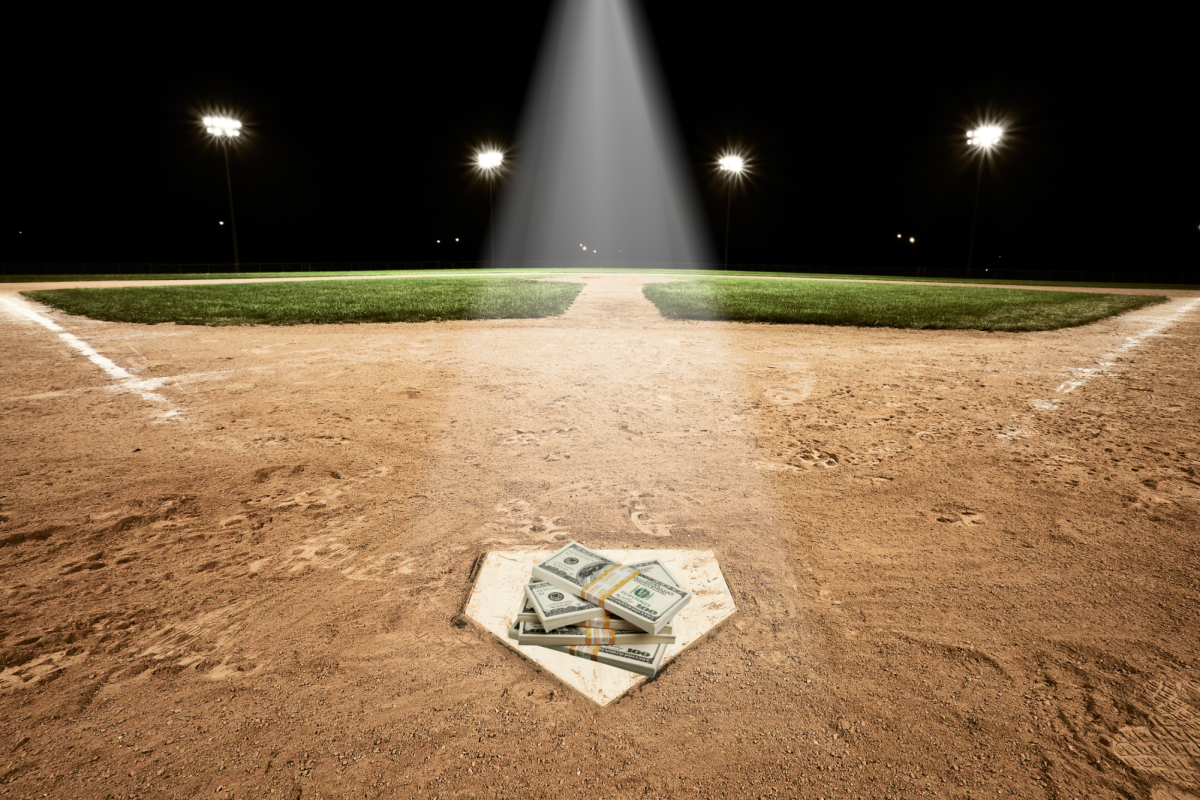

The sun sets in Wayland through a haze caused by smoke from the California wildfires, brought to the East Coast by the jet stream. The fires are the worst in 18 years and have burned over 3.1 million acres. “[Wildfire] activity this year has been tens to hundreds of times more intense than the 2003–2019 average in the US in general, as well as in several affected states,” Europe’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service reported.

September 29, 2020

Although Massachusetts is thousands of miles away from the West Coast, it is still seeing the effects of the wildfires in California and Oregon. The fires produce vast plumes of smoke that are caught in jet streams and carried across the country to the East Coast. However, it doesn’t stop there: the smoke is believed to be traveling across the Atlantic ocean and worldwide.

Those in the Midwest, New York, and New England recently noticed a haze in the sky and the muted presence of the sun. Massachusetts residents also may have smelled burnt wood, but the air quality was not affected as the smoke was very high in the atmosphere.

The wildfires devastating California, Oregon, and other parts of the western United States began in mid-August and have burned an area of over 3.1 million acres creating a total of 6.7 million acres burned so far this year. The fires are record-breaking and the worst in 18 years, CNN reported. Their increasing prevalence and intensity have also been linked to climate change.

“[Wildfire] activity this year has been tens to hundreds of times more intense than the 2003–2019 average in the U.S. in general, as well as in several affected states” according to data from Europe’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS).

Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon described the wildfires as “apocalyptic” on the ABC program ‘This Week.’

Almost 50 million people in California, Oregon, and Washington, who are each one in seven Americans, experienced no less than one day of “unhealthy” or worse air quality so far this year, an NPR analysis of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency air quality data reported.

Furthermore, Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco are said to have the worst air quality of any major cities around the world, as stated by IQAir, a company that tracks air quality.

At least 35 people have been killed in the fires and many more could possibly have health repercussions. The CDC says smoke exposure increases respiratory and cardiovascular hospitalizations and respiratory infections.

The wildfires are impacting greenhouse gas emissions globally as well. It’s estimated that the wildfires on the West Coast this year have generated more than 91 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, according to data from the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED).

That would be about 25% more than the annual fossil fuel emissions in California, atmospheric scientist from Cardiff University Niels Andela told Mongabay.com.

“We estimate… that this is the highest year we have on our record, at least,” Andela said. “In ideal conditions when those forests are able to regrow, they will eventually reabsorb those emissions again, although that may take many decades… but for some of those forests, it might be really hard to fully recover.”

“We estimate… that this is the highest year we have on our record, at least,” Andela said. “In ideal conditions when those forests are able to regrow, they will eventually reabsorb those emissions again, although that may take many decades… but for some of those forests, it might be really hard to fully recover.”

These emissions could be part of a cycle that may create more wildfires in years to come. As rising global temperatures generate drier conditions in forests and longer fire seasons, larger areas of forests and other vegetation are burned. Emissions from these fires cause additional atmospheric carbon which drives further warmth and temperature rises.

“The more that we can do to limit the degree to which temperatures rise is fundamental to how frequently we see dangerous fire weather in the future,” Professor Richard Betts from the University of Exeter told BBC News.

![Last Wednesday, the Wayland School Committee gathered to discuss a number of topics regarding the health curriculum and Innovation Career Pathway course. Another large topic of conversation was the ways to potentially mitigate distracting cell phone usage. "These [phones] are going to distract your learning and social relationships," Superintendent David Fleishman said. "That's concrete right there."](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-04-at-9.49.31 PM-1200x886.png)

![Troy Hoyt finishes the Boston Marathon, running for the Hoyt Foundation. T. Hoyt is the son of Hoyt Foundation CEO Russ Hoyt.

“[Running a marathon] might seem like a big thing, when it’s presented to you at first, but if you break it up and just keep telling yourself, “Yes, you can,” you can start chipping away at it. And before you know it, you’ll be running the whole 26 miles, and you won’t even think twice about it.” T. Hoyt said.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/C36E8761-1CBB-452E-9DF2-543EF7B1095E_1_105_c.jpeg)

![The sun sets in Wayland through a haze caused by smoke from the California wildfires, brought to the East Coast by the jet stream. The fires are the worst in 18 years and have burned over 3.1 million acres. "[Wildfire] activity this year has been tens to hundreds of times more intense than the 2003–2019 average in the US in general, as well as in several affected states," Europe's Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service reported.](https://waylandstudentpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Screen-Shot-2020-09-28-at-1.40.29-PM-900x604.png)